- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: 1985 ★★★★

- Custom Highlight Text:

At the 2019 Melbourne Queer Film Festival, a friend and I were discussing the work of the Texan-based, Malaysian-born filmmaker Yen Tan. Having just seen his latest film, 1985, I was struck by the subtle power of the film. Aesthetically, it might have been made in 1985. As with all his films, there is a non-sensationalist sadness that gradually builds ...

Jamie Chung as Carly and Cory Michael Smith as Adrian in 1985 (photograph by HutcH/EPK)

Jamie Chung as Carly and Cory Michael Smith as Adrian in 1985 (photograph by HutcH/EPK)

Adrian, closeted to all these figures, is afraid to let his family know that he is dying of AIDS. Physically he does not belong in this cosy, suffocating house: he lurks in doorways, uneasy in his father's presence.

In order to bond with Andrew, Adrian accompanies him to the cinema where they see the 1985 cult horror film Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge. Queer film scholars such as Harry M. Benshoff have written extensively about the homoerotic undertones in this film, which sees Freddie Krueger possess the young Jesse (Mark Patton). Jesse struggles with the power Krueger has over him, this demonic possession equating to unwanted same-sex attraction. This is a particularly apt for Tan, as Adrian himself goes through a similar conflict with his own family. This internal struggle has created its own demon, which he must quash.

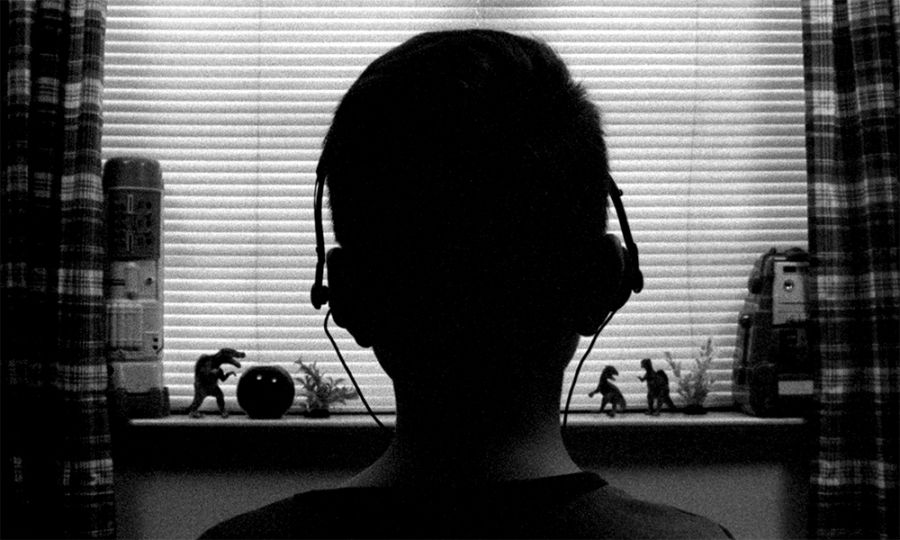

Sadness and nostalgia permeate 1985. This era marked a significant juncture in queer history, and the film seems like one of its lost relics. The film is shot in black-and-white 16mm, replicating low-budget filmmaking from that period. Many shots linger, a device that allows us to reflect on Adrian’s difficulty to connect with those around him. Ironically, 1985 couldn’t have been made during the 1980s. The anger and panic of that epoch are absent, leaving a quiet melancholy. Buddies (1985) and Parting Glances (1986) – the first films to deal with the AIDS pandemic – had to deal the momentousness of this representation. There is a rawness to 1985 that is reminiscent of the films from the New Queer Cinema wave of 1991– 92, such as Poison, Swoon, and The Living End. It is difficult, however, to separate them from the pandemic they describe.

Aidan Langford as Andrew in 1985 (photograph by HutcH/EPK)

Aidan Langford as Andrew in 1985 (photograph by HutcH/EPK)

1985 feels simultaneously historical and contemporary. It is a simple film about sadness, family, and love. Tan’s film also has the difficult task of standing apart from the plethora of HIV-related films that followed Buddies and Parting Glances. (In 2018 BPM, for instance, won rapturous critical praise, including in Anwen Crawford's review for ABR)

The intervening decades have offered us greater perception. Each character’s perspective is explored. Adrian’s parents are imbued with psychological depth as the narrative unfolds. Michael Chiklis’s Dale reveals a hurt father who struggles to comprehend why his son is so remote. Jamie Chung offers wonderful rapport with Cory Michael Smith, as the pair attempt to repair a fractured friendship.

Virginia Madsen’s Ellen is perhaps the most enigmatic character. Adrian constantly rebuffs his cheery mother. Does she really know why Adrian is so distant? Finally, if we are to read Andrew, the young brother, as a burgeoning gay man, the interactions between the two brothers convey a certain handing of the baton between generations. This adds a level of hope for Andrew’s future happiness, an element only possible because of these thirty-plus years of perspective. His generation won’t be marked by this senseless, tragic loss.

1985 (EPK), 85 minutes, directed by Yen Tan. In cinemas 25 April 2019.