- Free Article: Yes

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: McQueen ★★★★

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

In old interview footage included in the documentary McQueen, the late British designer Lee Alexander McQueen states, ‘If you want to know me, just look at my work.’ Relatively few had the privilege of seeing his extraordinary designs on the runway firsthand. Many more got to witness ...

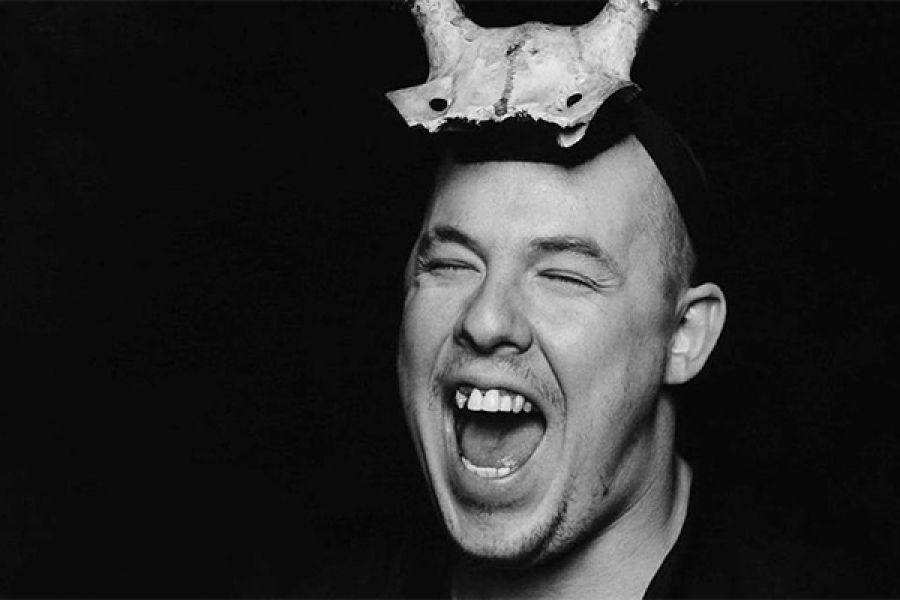

Alexander McQueen with a model (Madman Films)

Alexander McQueen with a model (Madman Films)

The film’s first instalment, ‘Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims’, is named after McQueen’s 1992 graduate collection. Already the combination of beauty and darkness that suffuses McQueen’s designs is apparent. Similar themes were explored in later collections, such as Highland Rape (Autumn/Winter 1995–6), VOSS (Spring/Summer 2001), and Widows of Culloden (Autumn/Winter 2006–7). These shows were frequently controversial, causing outraged headlines in the the British press, but in an early interview McQueen aptly explains that he did not want you to come out of his shows ‘feeling like you’ve just had Sunday lunch’. He wanted to make people feel ‘either repulsed or exhilarated, as long as it’s an emotion’.

McQueen’s passionate desire to create clothing that provoked an emotional response is captured well in the film, and its collaged, ad hoc structure is particularly effective in conveying the exhilarating thrill of the designer’s early years. With very little money but an iconoclastic spirit and belief that anything was possible, McQueen embarked on a journey of breathtaking creative inventiveness. The documentary also draws attention to the coterie of family and creatives that surrounded and aided the designer. This included Isabella Blow, the fashion magazine editor who bought McQueen’s entire graduate collection and became a mentor and muse to the designer. (It was Blow’s suggestion to drop ‘Lee’ from the name of his fashion house so that it sounded more esteemed.) When McQueen becomes head designer at Givenchy in 1996 and he and his close-knit team head to Paris, the youthful energy and punk attitude that they bring to the traditional French fashion house is palpable.

A model exhibiting one of Alexander McQueen's designs (Madman Films)

A model exhibiting one of Alexander McQueen's designs (Madman Films)

But it is also around this time that McQueen’s own demons become more apparent. The pressure to design multiple collections a year for Givenchy as well as his own label was intense, and while he occasionally used models who did not conform to the fashion world’s narrow notion of beauty, he struggled with his own body image and eventually underwent liposuction. McQueen’s childhood abuse by his violent brother-in-law is touched upon, as is his drug use as an adult. The filmmakers also do not shy away from acknowledging McQueen’s possessive, sometimes hurtful personality. His temporary rift with Isabella Blow is particularly poignant.

In 2010 McQueen’s beloved mother died, and on February 11, at the age of forty and on the eve of his mother’s funeral, Lee McQueen committed suicide. For viewers familiar with the designer and his work, the documentary’s lack of focus on certain key people in his life may be rather jarring. His long-term assistants, Katy England and Sarah Burton – the latter appointed creative director at Alexander McQueen after his death – and his late partner, George Forsyth, whom he ‘married’ in Ibiza (the ceremony wasn’t legal), are barely mentioned. Yet, despite these omissions, the filmmakers have made a fitting tribute to the man that was, and the fashion legend that is, Alexander McQueen.

Alexander McQueen with his mother, Joyce. (Madman Films)

Alexander McQueen with his mother, Joyce. (Madman Films)

Near the beginning of the documentary, McQueen says of his creative inspiration that he would ‘pull these horrors out of my soul and put them on the catwalk’. The tragedy is that, while these horrors helped McQueen to realise his dark, divine creations, they eventually overwhelmed him.

McQueen (Bleecker Street), 111 minutes, directed by Ian Bonhôte and co-directed/written by Peter Ettedgui, screened at the Sydney Film Festival in June and the Melbourne International Film Festival in August. It is in cinemas from 6 September 2018.

ABR Arts is generously supported by The Ian Potter Foundation and the ABR Patrons.