- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: Babygirl

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Babygirl

- Article Subtitle: Milk break in corporate America

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

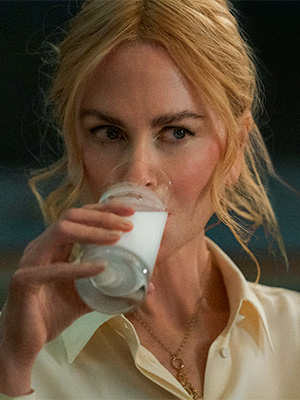

Right now on the website for A24 – the reigning enfant terrible of indie American film distribution – you can buy a ‘Babygirl Milk Tee’ for $40, a T-shirt prominently featuring an image of a tall glass of milk. This is an allusion to one of the more memorable moments in Halina Reijn’s Babygirl, when upstart intern Samuel (Harris Dickinson) surreptitiously purchases a glass of milk for his much-older boss, Romy (Nicole Kidman), at a work function, then watches her drink it in a single gulp; a semi-public display of psychosexual domination. - Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Nicole Kidman as Romy (photograph by Niko Tavernise, courtesy of A24)

- Production Company: A24

Romy is CEO of a New York-based warehouse robotics company, screenwriting shorthand for an ambitious, career-focused woman whose life is built upon order and predictability. She lives in a Manhattan penthouse with her picture-perfect family, including her theatre director husband, Jacob (a refreshingly against-type Antonio Banderas). Before we see a frame of footage in Babygirl, we hear the sounds of Romy and Jacob’s sexual congress; theirs is by no means a loveless marriage. But only moments later, Romy sneaks off to a spare room to satisfy herself while watching submission fetish porn. So far, so standard for the classic erotic thriller formula. Even though our high-powered heroine has it all, she is driven by the search for something different – something even more.

That something more, in Romy’s case, arrives just in time for Christmas in the form of Samuel, one of a batch of new office interns and the only one brave enough (or foolish enough) to ask Romy direct questions about her company’s ethics and to point out the post-Botox bruises on her cheeks. Their workplace banter quickly escalates into a full-blown affair – solidified in no small part by that glass of milk – with Romy seemingly having found an outlet for her ‘deviancy’, which involves not merely domination but outright degradation. Babygirl’s most compelling moments involve Kidman showing us Romy grappling with, then finally giving over to, these long-repressed desires (if only Jasper Wolf’s restless camera would let us focus on a character’s face for any meaningful stretch of time). But as anyone well-versed in erotic thrillers ought to know, getting what you want is only half the story. The other half is trying to put the genie back in the bottle, a unique challenge in this case, given that Romy admits the risk of ‘losing everything’ is her biggest turn-on.

Harris Dickinson as Samuel (photograph by Niko Tavernise, courtesy of A24)

Harris Dickinson as Samuel (photograph by Niko Tavernise, courtesy of A24)

Another recent descendant of Fatal Attraction (1987), Indecent Proposal (1993), Disclosure (1994), and the like, Fair Play (2023), written and directed by Chloe Domont, was a vivid collision of sexual and corporate power dynamics set at a high-stakes Manhattan investment firm, earning its genre stripes through the mutually assured destruction of its two horny, ambitious leads. In the modern erotic thriller pantheon, Babygirl feels docile by comparison, retreating to the safety of pop psychology whenever it threatens to do anything truly transgressive. Each of its individual elements – from Kidman’s go-for-broke performance to the wonderfully bacchanalian score from Cristobal Tapia de Veer (best known for the opening theme music to HBO’s The White Lotus) – hints at a more daring and subversive film. For the most part, Reijn’s stylistic naturalism is at odds with her story’s genre roots, and the end result feels frustratingly tentative: a film unwilling to fully commit to its own anthropological enquiries and unwilling to make its characters pay any meaningful price.

Babygirl suffers further by inevitable comparison to not one but two separate films from Kidman’s oeuvre, the first being Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999), in which another high-powered New York professional (Kidman’s husband-at-the-time, Tom Cruise) teeters on the brink of a sexual abyss (and at Christmastime no less); the second being Jonathan Glazer’s Birth (2004), an infinitely thornier age-gap drama in which a New York widower (Kidman) entertains the notion that a ten-year-old boy might be her reincarnated husband. Kidman has never shied away from provocative material, and her courage and flexibility as a performer is key to these films’ legacies. Decades on, however, Kidman’s projects often struggle to match her talent.

Meanwhile, Harris Dickinson – so fully realised and compelling in Ruben Östlund’s Triangle of Sadness (2022) – is underutilised in the role of Samuel, the latest in a long line of sexy cinematic interlopers with the power to burn their lovers’ carefully curated worlds to the ground. Samuel is a cipher with a non-existent backstory; seductive when he needs to be, threatening as the plot demands, and conveniently absent otherwise. This would appear to contradict one of his own early dictums to Romy: ‘I’m not a toy you can pick up and play with.’ Reijn’s script treats him exactly as such.

The most radical thing about Babygirl might be the way it spins the forbidden fruit of its central relationship into a genuinely heartfelt treatise on sex positivity and intergenerational acceptance. Romy’s attraction to Samuel is not merely because of his youthful good looks, but because of the world view that that youth grants him. While Jacob is quick to dismiss ‘female masochism’ as a wholly ‘male fantasy’, Samuel disagrees, and treats Romy’s kinks with the respect he believes they deserve. Similarly, once the cat is fully out of the bag, it is Romy’s teenage daughter Isabel (Esther McGregor) who reassures her that infidelity is not the cardinal sin it used to be. Even Romy’s ambitious young EA, Esme (Sophie Wilde), chooses to leverage the scandal not to ruin her boss’s career but to help get that storied career back on track. When this generation takes over corporate America, could that be the end of workplace drama as we know it? Great news for employees; a great loss for the genre.

Babygirl (A24) is in cinemas nationally from 30 January 2025.