- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: The Brutalist

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Brutalist

- Article Subtitle: Brady Corbet’s pursuit of historical hinge points

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text: Brady Corbet made his first film, The Childhood of a Leader, when he was twenty-four. A former child actor, he came to directing after years as the Zelig of the arthouse, acting in films by auteurs such as Michael Haneke and Lars von Trier. When The Childhood of a Leader premièred at the Venice Film Festival in 2015, Jonathan Demme (The Silence of the Lambs), serving as the president of the Orizzonti jury, likened Corbet to Orson Welles, an invocation so sacrilegious it was sure to provoke the ire of certain American critics, who have had Corbet in the gun ever since.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

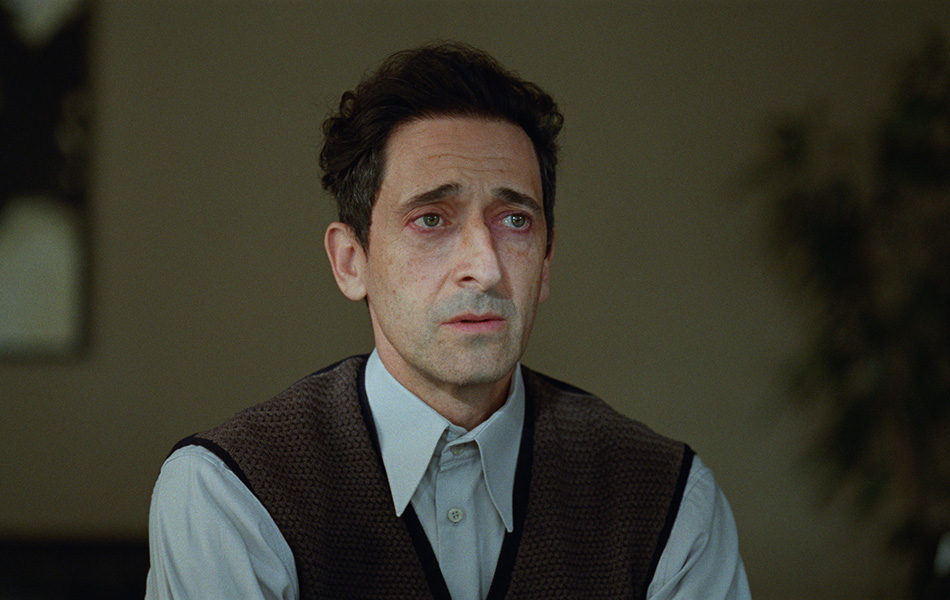

- Article Hero Image Caption: Adrien Brody as László Tóth in The Brutalist

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Adrien Brody as László Tóth in The Brutalist

- Production Company: Universal Pictures

If not quite Citizen Kane, Corbet’s début was certainly bold, and it established the director’s interest in mapping historical hinge points. The film posits a diplomat shepherding the Treaty of Versailles as the father of fascism; his unbiddable little boy grows up to become a Stalinesque dictator. Corbet’s point was blunt and not exactly ground-breaking, and his characters felt representational rather than human. The same was true of his next film, Vox Lux (2018), which examined the commodification of trauma through the survivor of a school shooting, who is catapulted to pop stardom after singing at a televised memorial for her classmates.

His first and – to date – only film shot largely in America, Vox Lux was an unhappy experience for Corbet. He has spoken about a moneyman forbidding the use of a slider (a lightweight and inexpensive piece of kit that lets filmmakers dolly the camera without the time-consuming laying of tracks) because the budget supposedly wouldn’t allow it.

Corbet writes his scripts with his wife, Norwegian director Mona Fastvold. The couple started working on a film about the relationship between an architect and the man holding the purse strings – as with filmmakers, an architect’s work is contingent on considerable money and manpower. After making two films in short order, this one took six years to get made, but the interregnum seems to have been beneficial: among many other things, The Brutalist represents posthumous vindication for Demme, who clearly saw something the rest of us missed.

Guy Pearce as Harrison Lee Van Buren and Adrien Brody as László Tóth in The Brutalist

Guy Pearce as Harrison Lee Van Buren and Adrien Brody as László Tóth in The Brutalist

Like The Childhood of a Leader, The Brutalist begins in the immediate aftermath of global cataclysm. An architect trained at the Bauhaus and responsible for several public buildings at home in Budapest, László Tóth (Adrien Brody) survives his internment in Buchenwald and books passage to America. When he arrives, Tóth jumps on a bus to Philadelphia to stay with a cousin; in a lovely grace note, the camera lingers on the shipmate he will never see again as the bus pulls away. In Philly, he catches the eye of magnate Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce), who made his fortune in the wartime supply business and commissions him to build a community centre – a shining city upon a hill, if you will, in the cradle of American liberty.

No prizes for guessing where this is going. Pearce has been doing louche villainy better than anyone since The Count of Monte Cristo (2002), and he manages to sell Van Buren’s intellectual pretension without tipping too far into outright buffoonery, while Brody conveys the kind of unadorned directness and self-possession that draws people in, making Tóth an object of desire as well as resentment – sometimes both at once.

But Corbet isn’t just exploding the myth of the American dream in The Brutalist, as so many filmmakers have done before him. He is interrogating the idea of liberty itself. What does that mean, and is it even possible? Tóth is reborn in America: we meet him climbing out of the dark belly of what turns out to be a ship. His ascent is overlaid with voice-over – a letter from the wife he doesn’t know is still alive, who ominously quotes Goethe just before her husband bursts into the new dawn: ‘None are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe themselves free.’

The sequence ends with the camera whip-panning upwards to find an inverted Statue of Liberty. The filmmaking in The Brutalist is exhilarating – Orson Welles also loved a canted angle, just saying! – and punch-drunk with the possibilities of the medium. Though it spans two hundred and fifteen minutes, there is a hurtling momentum to it, and not only in the sequences in which the camera speeds down roads and train tracks like a loosed arrow. Rushing headlong into the future is a theme, and Corbet splices in archival footage of Pennsylvania industry and radio broadcasts on the formation of Israel.

The film’s script reportedly included photographs in the manner of W.G. Sebald, and its first half (before an intermission) takes its title from V.S. Naipaul’s novel The Enigma of Arrival (1987). Corbet has spoken of the influence both writers have had on his work, and it’s evident in his preoccupation with history as a cycle that repeats, in the porousness between past and present. That extends to the film’s own construction. Corbet and his cinematographer, Lol Crawley, decided to shoot in VistaVision, a format engineered in the 1950s with a higher-than-usual field of view. Corbet sought to summons the mid-century by emulating Hitchcock’s blocking of actors.

The film’s second half (‘The Hard Core of Beauty’) marks the arrival of Tóth’s wife, Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), confined to a wheelchair after malnutrition-induced osteoporosis, and the couple’s niece, Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy). Jones is shrewdly cast, bird-like but with a convincing intelligence and steel. Zsófia, meanwhile, has been rendered mute by her wartime experiences. The first time we hear her speak, years after her arrival in America, she announces her intention to move to Israel – to the horror of her adoptive parents.

Zsófia takes centre stage in the film’s epilogue, as Daniel Blumberg’s lush and blanketing score shifts from sepulchral horns to chimes and into a synth beat – all the better to celebrate the first retrospective of Tóth’s work, recontextualised by his niece as the means by which he transmuted trauma into art. This is the artist as smuggler, embedding hidden meanings in his own construction.

Given how closely The Brutalist attempts to mimic the scale, ambition, and intricacy of its protagonist’s work in the film’s own design, it is worth asking if Corbet has engineered a similar trick. Zsófia is the first person we see in The Brutalist, under interrogation by border guards. ‘What is your true home?’ they ask her. The girl’s inability to answer means that the question hangs over the film. Three decades later, she has found both her voice and her homeland. The final destination is what matters, she says. But a cross-fade to the girl she was – the prisoner she was – hints that Zsófia’s freedom is illusory, provisional, and that her aunt’s Goethe warning has been forgotten.

The Brutalist (Universal Pictures) is in cinemas nationally from 23 January 2025.