- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Custom Article Title: Qui a tué mon père (Who killed my father)

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Qui a tué mon père (Who killed my father)

- Article Subtitle: Édouard Louis’s states of precarity

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For the past decade, French writer Édouard Louis has been excavating and recuperating a childhood spent in a state of acute precarity in the Hauts-de-France. He has written both critically and empathetically about the lives of his parents and siblings, while also casting a probing eye on himself. His first novel, the autofictional En finir avec Eddy Bellegueule (The End of Eddy, trans. Michael Lucey, 2014), was published when he was only twenty-two and has enjoyed significant success in translation.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

.jpg)

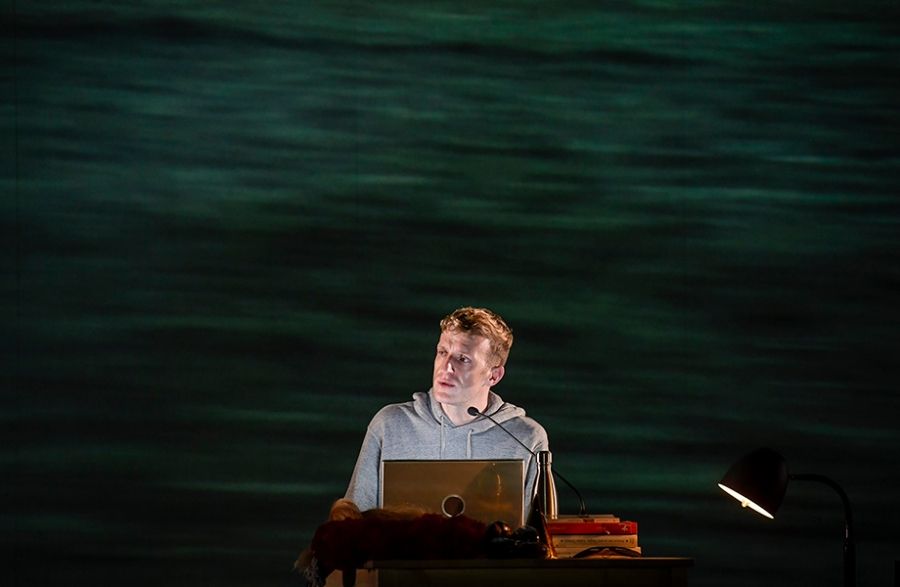

- Article Hero Image Caption: Édouard Louis in Qui a tué mon père (photograph by Roy Van Der Vegt)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Édouard Louis in Qui a tué mon père (photograph by Roy Van Der Vegt)

- Production Company: Schaubühne Berlin and Théâtre de la Ville Paris

Louis is undoubtedly and unabashedly a political writer, and his 2018 book, Qui a tué mon père (Who killed my father, trans. Loren Stein), is no exception, even perhaps the most overtly political of his works to date (not including his most recent novel, Changer: methode, which appeared in English as Change, trans. John Lambert, very recently). A monologue-meditation, Qui a tué mon père is informed by Louis’s childhood in poverty, assailed by homophobic attitudes, and a life beyond that experience, which has seen him move to Paris and into a world of bourgeois intellectualism. There he has been mentored by the philosopher Didier Eribon, himself the author of a magnificent memoir, Retour à Reims (Returning to Reims, trans. Michael Lucey), about coming to terms with his own working-class background.

Four years ago, during the first months of the pandemic, German director Thomas Ostermeier premièred a one-man stage adaptation of Qui a tué mon père at the Théâtre des Abbesses in Paris. The production had its Australian première at the Adelaide Festival on 8 March this year, to a warm reception and standing ovations. (Earlier, at Writers’ Week, Louis was in conversation with Ruth McKenzie, Artistic Director of the Adelaide Festival.)

Édouard Louis in Qui a tué mon père (photograph by Roy Van Der Vegt)

Édouard Louis in Qui a tué mon père (photograph by Roy Van Der Vegt)

Performed by Louis in French with English surtitles (though these occasionally flatten the original language and leave some passages untranslated), the play begins even as the audience is entering, with Louis already on stage and typing away at a laptop, making notes to one side, sipping from a canteen. One way of understanding the play’s form is to see it as an essay that we enter in medias res; in fact, all of Louis’s work is potentially understandable in this way. To enter his world on the page or in person is to find oneself in a flow of ongoing critical self-reflection.

Louis’s work has at times had an unjustly mixed critical reception. In France, centrist and right-wing publications have charged him with what they take to be whininess, narcissism, and repetition. Certain gatekeepers never want to admit people such as Louis, no matter how fine and arresting their work. There will always be a complaint, whether about the nature of the work itself, or the man standing behind it. To come from a working-class background, to be homosexual, to insist that literature can and must be a space for left resistance seems to inflame the prejudices of those who have never had to question their place in the field of cultural or intellectual production.

Even in English, reviewers in leading global newspapers have taken Louis to task for daring to insert the political and theoretical into the literary, as if an art evacuated of politics were not itself deeply political (and most often reactionary). Such hostile reviews are nearly always judging the work by the wrong criteria, implicitly holding it up against a body of largely realist literature that is trying to achieve different effects entirely than those that compel Louis. We should rather look to his fellow French writer, Nobel Laureate Annie Ernaux, or to any number of other European writers and artists, to understand the traditions in which his work is participating and making its own significant contribution.

All that said, I was expecting Louis to be something other than the person I witnessed on stage at Adelaide’s Dunstan Playhouse. I did not anticipate that Qui a tué mon père would offer such an intensely felt and nuanced performance, and one that refuses the tired trappings of theatrical realism in favour of a Brechtian-inflected direct address (to the absent father, to the audience). The work on stage seemed often to function as an exorcism of the ghosts with whom Louis continues to grapple, and in a way that was more emotionally urgent than the adapted book can sometimes seem.

When he begins speaking to his absent father, embodied by a leather armchair at the front of the stage and positioned in a diagonal line from the desk, it is difficult to imagine anyone not feeling moved. If one knows his work, it is impossible to forget that the charming and charismatic person standing before you on stage has also been raped by a one-night stand, an experience that gave rise to (in my view) his most important and formally inventive book, Histoire de la violence (History of Violence, trans. Lorin Stein, also directed by Ostermeier in a stage adaptation). To be conscious of this is to understand the high-wire act to which Louis has committed himself, one demanding a balance between commitment to formal innovation that often foregrounds the constructedness of a particular work, and the searing intimacy of the revelations he is prepared to offer.

A video projection at the back of the stage frames much of the play as a road movie traversing the unlovely motorways of France’s industrial north. This imagery recalls similar moments in Agnès Varda’s The Gleaners and I (2000), a documentary essay-film on precarity in France’s regions, and the comparison offers another way of understanding what Louis is doing: blending the personal and political to make an incisive argument that is also painfully self-revealing. The collision of these two impulses manages, when embodied by Louis on stage, to produce moments of unconventional, brutalist beauty.

If this all sounds so serious as to be exhausting, the staging of Qui a tué mon père is often surprisingly fun – funny and queer in a way that is not as evident on the page. References to Louis’s childhood acts of drag-adjacent performance become, on stage, opportunities to dance joyously, both in and out of drag, to Aqua’s ‘Barbie Girl’ and Britney Spears’ ‘…Baby One More Time’. A lip-sync to Whitney Houston’s cover of ‘I Will Always Love You’, ‘sung’ to his absent father, is disarmingly tender.

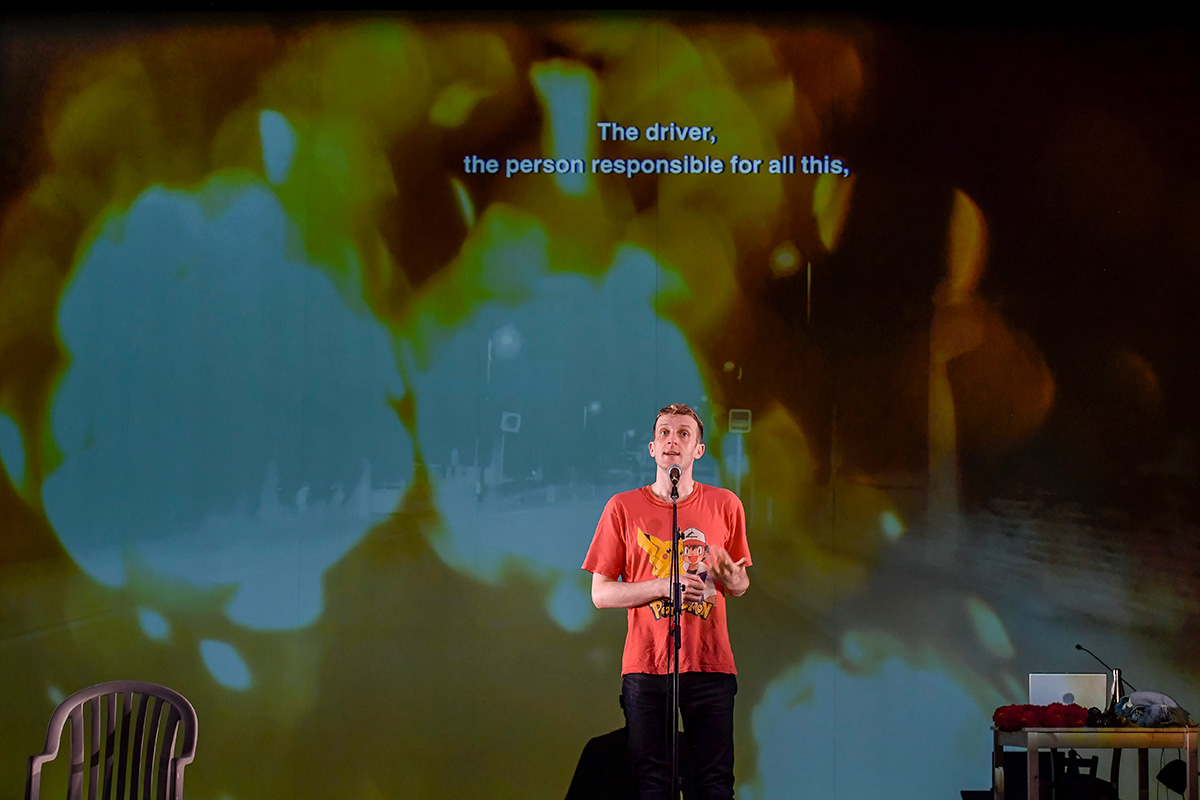

It would be a mistake to search for anything like conventional dramatic coherence, let alone narrative unity, in this work: it is, rather, an essay in lyric fragments that left me convinced that Louis’s project (perhaps his entire oeuvre to date) is an act of multi-textual and multi-media becoming. When, in this production, he inhabits himself as a child in a Pokémon T-shirt (we see the reference photograph on the rear projection) and tells the audience, briefly switching to English, about a catastrophic family fight, the emotional temperature of the piece reaches its peak. Addressing the audience rather than the absent father for the only time in the show, he recounts how his mother used a homophobic epithet against him as a young child, and describes the suicidal feelings he experienced as a result. The words feel almost unscripted, extemporised. One senses this is an artist trying to make himself whole through acts of re-inscription and artful repetition.

Louis does, ultimately, answer the question about who he believes must answer for his father’s untimely ill health. In a tableau that unites elements of a child’s magic show with party games and street protest, he assails leaders from across the span of France’s political spectrum, holding them responsible for decisions that have routinely punished the poor and rewarded the rich. His father, meanwhile, has undergone an ideological transformation. This man who used to side with the racist right now tells his son, ‘What we need is a good old revolution.’

In a moment when fascism has made alarming inroads into the political mainstream across Western democracies, Édouard Louis offers us a compelling ode to the hope that anyone’s views may be changed for the better, if only we can find the right words to show them the way, and to hold the powerful accountable.

Qui a tué mon père (Schaubühne Berlin and Théâtre de la Ville Paris) was performed at the Dunstan Playhouse from 8 to 10 March 2024. Performance attended: 8 March.