- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Custom Article Title: Seventeen

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Seventeen

- Article Subtitle: A lively, mawkish exercise in nostalgia

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text: In his program notes for the Melbourne Theatre Company’s production of Seventeen, playwright Matthew Whittet describes the play as ‘a conversation between generations. A conversation that acknowledges how hard it is to be on the brink of adulthood, but also how ridiculous and filled with utter joyful stupidity it is too.’

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Robert Menzies, Richard Piper, George Shvetsov, Pamela Rabe, Genevieve Picot (photograph by Pia Johnson)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Robert Menzies, Richard Piper, George Shvetsov, Pamela Rabe, Genevieve Picot (photograph by Pia Johnson)

- Production Company: Melbourne Theatre Company

Rather, Seventeen is a lively, if mawkish, exercise in nostalgia, one that speaks directly to those generations whose teenage years are long behind them. The play’s potency depends entirely on hindsight, relying on Boomer and Gen X audiences to imbue the action of the play with the abiding dreams, fears, and disappointments of their own adolescence.

High school forever finished, four seventeen-year-old friends gather at a local playground. With plenty of beer, spirits, snacks, and music on hand, they plan to spend one last night together before they head off into adulthood. The paths before them are vaguely mapped out – university, jobs in the family business, relocating to another state – but there is an uncertainty among them as to what it is that distinguishes their choices from their fate. As we will learn, each is bound by their own anchor, whether its family dysfunction, masculine bombast, or debilitating self-doubt. As the evening lengthens, the realities clawing at their dreams sharpen. What begins as a celebration veers steadily towards disillusionment.

Mike (Richard Piper) dominates the group. All blustering machismo, he orders the skolling of beers and endless games of ‘truth or dare’, devised (we discover) as a means of being forced to reveal his own unhappiness. His bold and confident girlfriend, Jess (Pamela Rabe), battles to assert herself and find a place where she might exist outside of the demands of either Mike or her alcoholic mother. Jess’s best friend Emilia (Genevieve Picot) – the smart, sensible, mother hen of the group – wants Jess to go to university with the rest of them, but Jess believes a course in hairdressing is, despite her desire to travel, her most probable future. Finally, there is Tom (Robert Menzies), hesitant, earnest, and closed-in on himself, his shoulders permanently hunched, his hands hidden in his pockets, his jacket wrapped around him in a gesture of self-protection. His parents are moving away, and he is being made to move with them. He dreads losing the comfort of being among friends with whom he is content to hang around doing absolutely nothing.

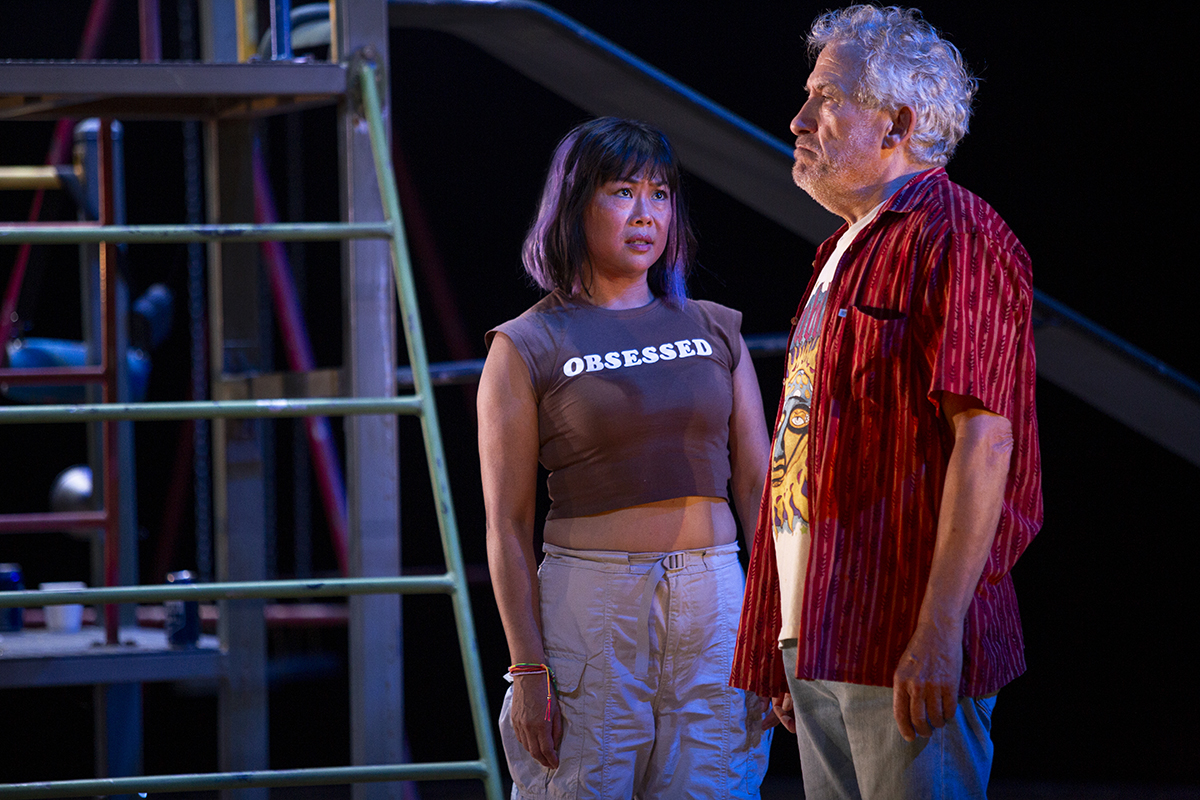

Fiona Choi and Richard Piper (photograph by Pia Johnson)

Fiona Choi and Richard Piper (photograph by Pia Johnson)

Two uninvited guests soon join the party. Lizzy (Fiona Choi), Mike’s exuberant and preternaturally wise younger sister, and Ronnie (George Shevtsov), a gangly schoolmate who seems to have not yet grown into his long, lank, out-of-control body. Ronnie is the outsider, the student with no friends and whom the others repeatedly misname. All Ronnie wants is to belong.

In its gathering together of mismatched adolescent types, each with their own plaintive backstory, Seventeen bears all the hallmarks of a John Hughes film. Hughes’s films – which dominated cinema in the 1980s and launched the careers of actors such as Rob Lowe, Molly Ringwald, and Matthew Broderick – were thoroughly of their time, consummately capturing the angst of teenagers as they strove to unravel, from a tangle of unrequited love and lust, neurotic families and muddled childhoods, their own dreams and futures.

Not only does Seventeen feel as though it speaks to the same generation of teenagers who devoured Hughes’s films, it adheres to a similar formula. Hughes’s The Breakfast Club (1985), in particular, comes to mind – ‘a brain, a jock, a rebel and a recluse’ (as the movie’s tagline identifies them) forced together in weekend detention. Whittet gives us different adolescent types, and a different variety of confinement, but it serves the same dramatic purpose, enforcing an intimacy in which hidden apprehensions and aspirations are made to reveal themselves.

What differentiates Seventeen from The Breakfast Club and Hughes’s other films is that each of the characters in Seventeen is played by an older actor, actors who embody, as Whittet rightly notes, ‘enormous amounts of craft and soul and history’. In an ensemble cast that works so seamlessly together, it seems unfair to single out individual performances. Nevertheless, mention must be made of Fiona Choi’s exuberant Lizzy (my companion at the theatre thought she was an actual teenager) and Robert Menzies’ soulful Tom. Menzies manages to turn two potentially dead scenes in the play into something quite profound, the audience leaning into the unease and ungainliness that he portrays.

As a concept, using older actors to play children or teenagers is not unprecedented. Caryl Churchill’s Cloud Nine (1979), for example, uses the conceit as a way of exploring gender roles and gender imprinting. Blue Remembered Hills (1979), Dennis Potter’s play about violent children, draws much of its emotional power, and its capacity to shock, from its use of adult actors in the roles of the children. In a similar vein to Seventeen, Roslyn Oades’s audio-scripted Hello, Goodbye and Happy Birthday (2014) sublimely explores the milestones of eighteenth- and eightieth-birthday parties by having older actors play eighteen-year-olds, and vice versa.

Overall, Whittet’s use of adult actors has the unsettling effect of these characters never seeming wholly adolescent nor wholly adult. The characters’ adult and adolescent tendencies come in and out of focus, rarely aligning, a disparate double vision that foregrounds the adults these teenagers seem doomed to become. Too often, however, it feels like we are watching not the youthful antics of nascent adults, but the dregs of a disappointing school reunion, a cluster of fifty- and sixty-somethings, in an odd mix of fancy dress (costume design by Christina Smith), revisiting that point in time where the course of their lives, for better or worse, was set in stone.

This sense of the essential circularity of life, of feeling as though you are moving forward but inevitably returning to the same unrealised hopes and complications you thought you had left behind you, is heightened by the production’s slowly revolving stage (set design also by Christina Smith). The playground, and the characters within it, turn full circle over the course of the play. As such, the advent of dawn (lighting design by Paul Jackson) seems less a beacon of hope than a poignant reminder of the same circularity.

For if Seventeen seems to say anything, it is that who you are as a teenager is who you are forever destined to be. It may not be the play’s objective, but it is nevertheless the impression that lingers. Much as the Jesuits boasted ‘Give me the child … and I’ll give you the man’, Seventeen, through its use of older actors, implicitly proposes that what our childhood years and their associated conditioning have hardwired into us is the adult we are bound to become. No matter our hopes and dreams, we are, Seventeen suggests, already bound to the path the first seventeen years of our lives have constructed for us, an inflection that gives the overwhelming sentimentality of the play a bitter (and I suspect unintended) aftertaste.

Seventeen (Melbourne Theatre Company) continues at The Sumner until 17 February 2024. Performance attended: 19 January.