- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Mahler’s Ninth Symphony

- Article Subtitle: The Australian World Orchestra’s 2023 feature

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Along with Beethoven, Schubert, and Bruckner, Gustav Mahler wrote nine symphonies. For each composer there was an incomplete, or unrecognised, tenth symphonic essay, which diligent musicologists have attempted to flesh out into meaningful ‘continuity scores’ or reconstructions. Mahler was barely fifty when he completed his Ninth Symphony and dared to tempt the fates with a Tenth; the growing seriousness of a heart complaint, however, meant that death, already a frequent visitor to earlier works, was never far from his mind. He died in 1911, not having heard in performance any of his Ninth (1909–10), his incomplete Tenth (1910–11), or his Das Lied von der Erde (Song of the Earth, 1908–9) – some four hours of his most moving music, much of which remained under-exposed for four decades until the ‘Mahler renaissance’ started in the 1950s.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Alexander Briger and the Australian World Orchestra (Helga Salwe)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Alexander Briger and the Australian World Orchestra (Helga Salwe)

- Production Company: Australian World Orchestra

The Australian World Orchestra, now well into its second decade, is a global curiosity: an ensemble for players who ‘still call Australia home’ but might hold professional positions anywhere in the world. They gather together just once a year for intense rehearsals and touring of a program or two. So, the Orchestra’s membership changes from year to year, depending upon player availability. This presents a challenge to the coordination and stylistic adjustment of the ensemble, but the advantage of a freshness and vigour to its performances. Alexander Briger – founder, artistic director, and, on this occasion, conductor – aims to produce performances ‘where you feel you have been moved to your very core, as I know we will be on stage’.

Mahler’s Ninth Symphony has been on Briger’s repertoire list ever since hearing sublime performances several decades ago in the hands of Georg Solti and Claudio Abbado. Given this advanced notice, his preparation for this Melbourne performance was immaculate; he conducted faultlessly from memory with close attention to the clarity of his cues to the players, whether old-hands or neophytes. So, for ninety minutes the near-capacity audience in Hamer Hall experienced a disciplined and consistent rendition, which explored the upper and lower reaches of the dynamic and pitch spectrums and faithfully followed the welter of Mahler’s verbal instructions, both in Italian and in German, which, laid end-to-end, rival the length of a novella.

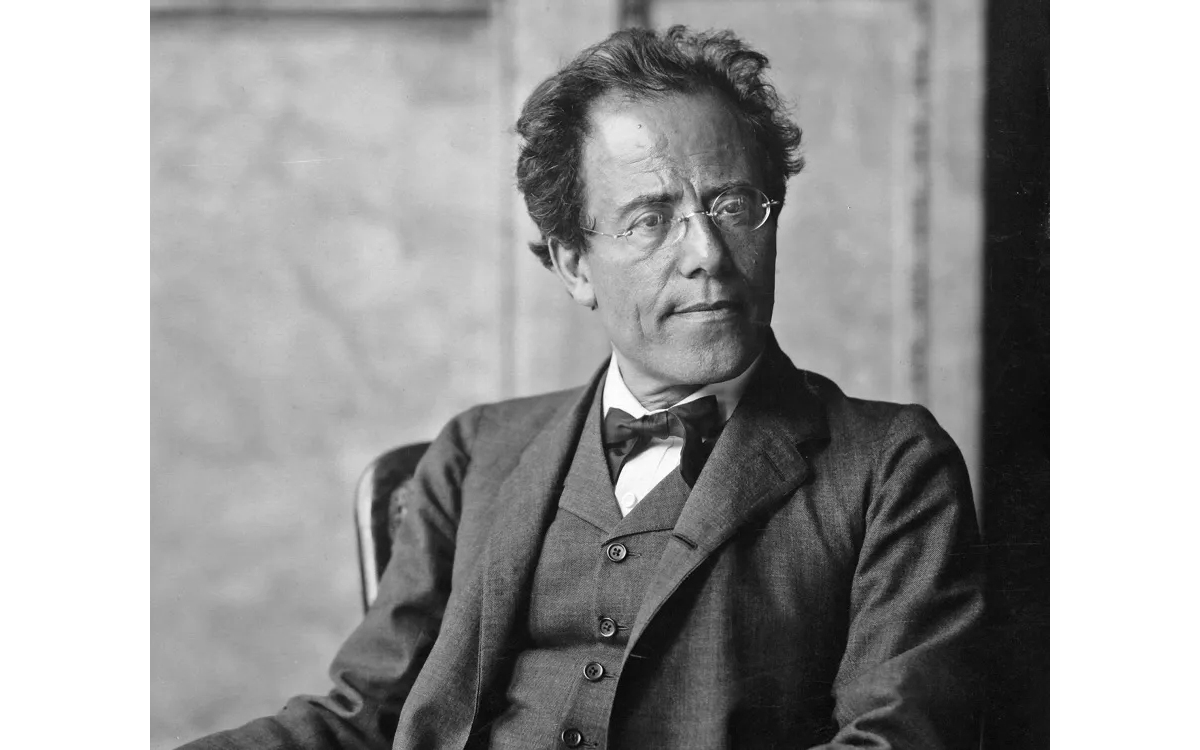

Gustav Mahler, 1907 (Moritz Nähr)

Gustav Mahler, 1907 (Moritz Nähr)

So far, so good. Mahler’s writing across his four movements for a massive orchestral resource is anything but ‘massed’. Although some of his climaxes, with the loud braying of brass and wind choirs, and the strings ‘screaming in the stratosphere’, are truly memorable, much of this symphony is about something more subtle: the cheeky interplay between the instrumental groups; complex, chamber music-like interactions within individual instrumental categories (for instance, the violins, horns, and clarinets); and Mahler’s calling upon most of the instruments for soloistic, cameo roles, even the piccolo and contra-bassoon (together) at the end of the second, dance-like movement. Briger was ever alert to these rapidly changing soundscapes, pulling back on accompanying figurations and drawing out the sometimes-unlikely soloists.

But here’s the rub. Amid all of this well-directed conductorial activity, all this attention to the interleaving of detail, I did not hear a compelling interpretation of a late-Mahler masterpiece. I guess I was looking for that guide to ‘distance hearing’, the larger sweep of things, that allows us to connect the various musical routines and sections across one and a half hours, and especially within the slow, half hour-long movements which bookend this symphony. You could say that the performance was thereby worth less than the sum of its parts. Perhaps this is an inherent danger in bringing together occasional ensembles, such as the Australian World Orchestra, rather than working within permanent ensembles over the years to bring their individual voices into line and forge a range of corporate interpretations, sometimes even in defiance of the conductor of the day! Most of us do not just remember a work, even a finely played one. We remember the brilliance, consistency, or outlandishness of its various interpretations, as indeed did Briger with those early Solti and Abbado performances.

Mahler symphonies are all the rage with Australia’s permanent orchestras at the moment so readers can make their own interpretative comparisons. Last year, Simone Young conducted the Second for the reopening of Sydney Opera House’s Concert Hall , and she will open the Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s 2024 season with the Fifth; Umberto Clerici has just performed the Sixth with the Queensland Symphony; Jaime Martín conducts the Third with the Melbourne Symphony in March; the West Australian Symphony Orchestra performs the Eighth (‘Symphony of a Thousand’), under Asher Fisch, next September; and the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra plays the First, next November. Along with Briger’s Ninth, we already have an Australian boxed Mahler set in the making.

The Australian World Orchestra repeats this program at the Sydney Opera House on 24 November 2023. Performance attended: 22 November.