- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Custom Article Title: Sibyl

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Sibyl

- Article Subtitle: William Kentridge’s unique visual language

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The use of the word ‘protean’ has become clichéd. Similarly, ‘Renaissance man/woman, polymath’ etc., have been used to describe many artists, perhaps never more appropriately than in the case of William Kentridge. His output is staggering, ranging over stage works, a wide range of performance art, installations, film, and several other areas, yet whatever the work might be, it is immediately recognisable.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

.jpg)

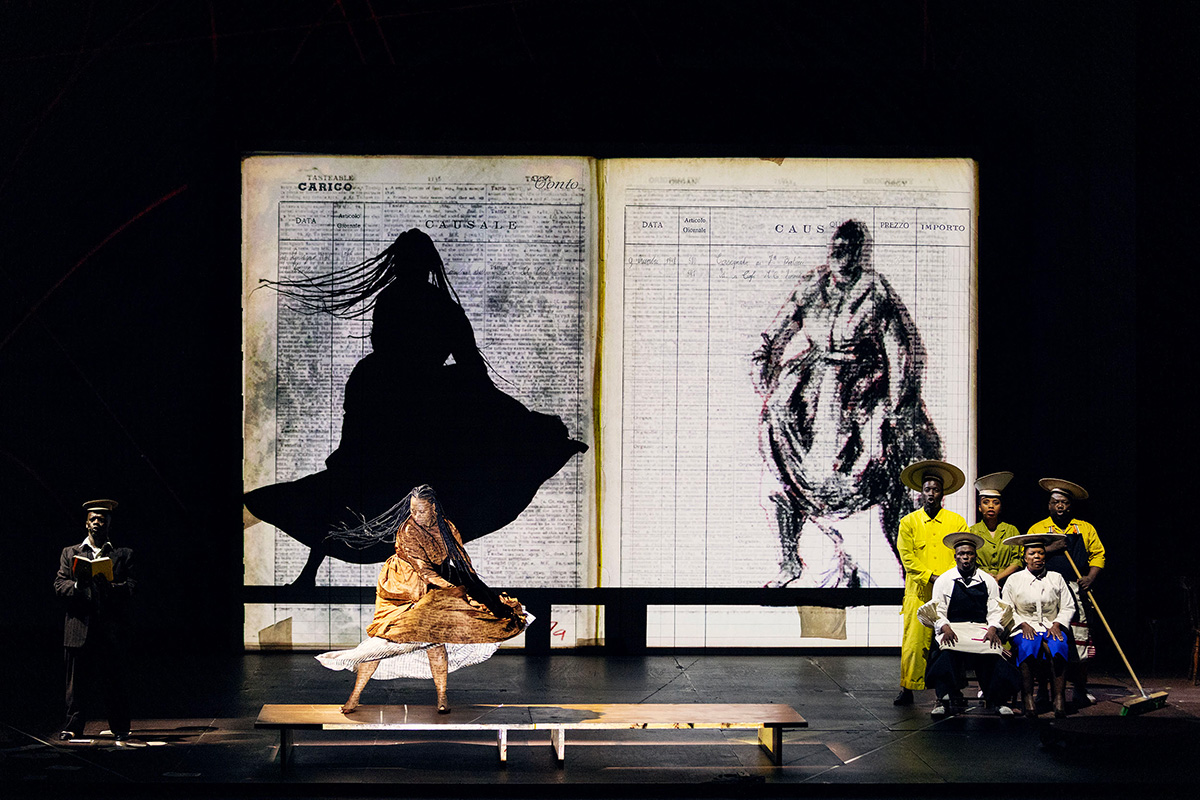

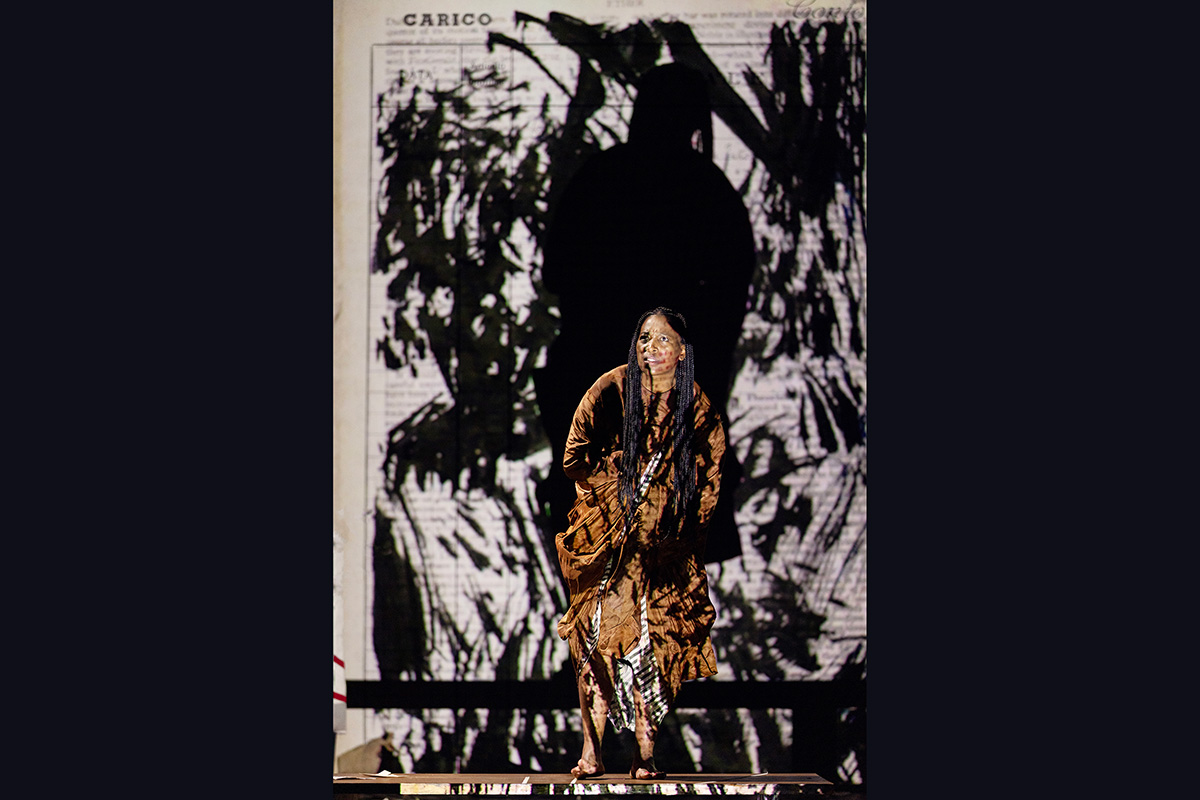

- Article Hero Image Caption: Sibyl (photograph courtesy of Sydney Opera House and by David Boon).

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Sibyl (photograph courtesy of Sydney Opera House and by David Boon).

- Production Company: Sydney Opera House

Sibyl (photograph courtesy of Sydney Opera House and by David Boon).

Sibyl (photograph courtesy of Sydney Opera House and by David Boon).

Kentridge’s first career choice was acting despite his obvious youthful artistic promise, strongly nurtured by his family. After completing a fine arts degree at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, he studied mime and theatre at the L‘École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq in Paris. He later, rather ruefully, observed: ‘I was fortunate to discover at a theatre school that I was so bad an actor that I was reduced to an artist, and I made my peace with it’.

Kentridge’s South African roots are crucial to an understanding of all his later work. His Jewish background and activist lawyer parents, who were deeply involved in the anti-Apartheid struggle, gave him what he described as a ‘third-party observer’ position in society. After his return to South Africa, he became involved in the vibrant protest theatre movement. However, it was his distinctive art that first drew wider attention, unique charcoal animations resulting in a sequence of drawings where the process of creation is laid bare. In an introductory note to a series of animated films, Felix In Exile, he observes:

In the same way that there is a human act of dismembering the past, there is a natural process in the terrain through erosion, growth, dilapidation that also seeks to blot out events. In South Africa this process has other dimensions. The very term ‘new South Africa’ has within it the idea of a painting over the old, the natural process of dismembering, the naturalization of things new.

Sibyl has its genesis in American sculptor Alexander Calder’s 1968 ‘Work in Progress’ for Rome’s Teatro dell’Opera, a large installation supported by electronic music created by three prominent Italian composers: Niccolò Castiglioni, Aldo Clementi, and Bruno Maderna. It consisted of large kinetic sculptures of brightly garbed cyclists who circled the stage describing a variety of figures, sometimes briefly revealing hidden images which are then obscured. In 2018, the theatre commissioned Kentridge to revive this work alongside a new piece from him. The Calder work inspired the idea of chaos morphing into coherence and then back to chaos, which became the central idea of Sibyl: investigating the role of prophecy in current culture. Kentridge notes:

Obviously, we rely on predictions of the future. Nowadays, we often find them in scientific ways rather than just prophecies. To know the weather, we just look at our phone, and there’s a prediction of what the weather will be the next day. In so many ways, algorithms, which take statistical examples of peoples’ desires and habits and are based on these generalized predictions made for specific people, are a kind of electronic form of prophecy, different from the Greeks’ way of examining the entrails of birds and fowls.

Like much of Kentridge’s work, Sibyl challenges generic definitions. For convenience in marketing, the term ‘opera’ has most often been applied to the work. Waiting for the Sibyl is through-composed without any spoken dialogue, which satisfies the most common definition of the term, but ‘opera’ does seem inadequate.

Sibyl was developed in the ‘Centre for the Less Good Idea’, where the artistic rationale is summed up in the South African Zwane proverb: ‘If the good doctor can’t cure you, find the less good doctor’; the idea being that the smaller ideas at the peripheries might become increasingly important as uncertainties grow concerning the large first idea. In musical terms, the core influence for Sibyl was Karl Heinz Stockhausen’s monumental Stimmung (1968) – a central work of the European modernist tradition – which is then fused with African musical traditions by a group of highly versatile musicians.

Sibyl is a double bill: the first part, The Moment has Gone, is a characteristic Kentridge twenty-minute short film, full of familiar images of the ‘Zama-zama’, the illegal miners who scratch a living of sorts from the ubiquitous disused mine dumps in the bleak Highveld landscape around Johannesburg. Kentridge himself is omnipresent in the film, furiously planning and sketching, often annoyed by his curious Doppelgänger. A range of kaleidoscopic images finally merge into art works hanging in the Johannesburg Art Gallery, a physical embodiment in bricks and mortar of the enormous wealth of gold mining in South Africa.

The work has four male singers in barber-shop close harmony, performing songs in English, Xhosa, Zulu, Sesotho, and Ndebele. Crucial to the whole project are jazz pianist, composer, and musical director of the project, Kyle Shepherd, and vocalist, dancer, choreographer, choral composer, and associate director, Nhlanhla Mahlangu. Shepherd describes composition as ‘improvisation slowed down’, and this reflects Kentridge’s drawings which make visible the painstaking process of their generation through constant erasures and changes. We see these forlorn figures undergoing a mythic metamorphosis into objects in nature, all underpinned by the music evoking Zulu ‘isicathamiya’ – unaccompanied choral singing. A final striking image is of the gallery disintegrating.

Sibyl (photograph courtesy of Sydney Opera House and by David Boon).

Sibyl (photograph courtesy of Sydney Opera House and by David Boon).

The second half of Sibyl is a forty-two-minute chamber opera, Waiting for the Sibyl, premièred in Rome in 2019, again with music by Mahlangu and Shepherd. Dominating the work are fragments of an enigmatic yet fascinating text, often in the form of pages of a book, flashing across a film screen revealing phrases soon obscured by others. Striking examples include the sayings: ‘Old Gods have retired / I no longer believe what I once believed; ‘It reminds me of something I can’t remember’; ‘Wait again for better gods / Wait again for better people’. Kentridge observed that he used roughly 200 phrases which are translations of poets or proverbs from Finnish, Hebrew, Spanish, Greek, Polish, Russian, and German sources, as well as those of his own invention. These phrases constitute the libretto of the opera whose central figure is the Cumaean Sibyl as found in Virgil’s Aeneid (the full libretto is available on his website). Kentridge’s rationale for the work:

You would go to the sibyl with questions of your life. ‘How long will I live? Will I survive COVID? What does my future have in store for me?’ You would write your questions on an oak leaf and put the leaf at the mouth of her cave. And she would write the answers on another oak leaf and put that oak leaf at the mouth of the cave. But, as you went to collect your leaf – the answer, your future – a wind would spring up, and all the leaves at the pile would swirl around. So, you could never tell if the leaf you were picking up was your leaf or the fate was fate that you were getting. That was, I suppose, the central metaphor of Waiting for the Sibyl.

The cast consists of nine superb performers: Nhlanhla Mahlangu, Xolisile Bongwana, Thulani Chauke, Teresa Phuti Mojela, Thandazile ‘Sonia’ Radebe, Ayanda Nhlangothi, Zandile Hlatshwayo, Siphiwe Nkabinde, and S’busiso Shozi. There are discrete scenes, some containing moments of great humour, including a hilarious slapstick scene in which Thulani Chauke is surrounded by chairs that slide away from him or even collapse as soon as he looks away. The ‘society’ depicted here lives by injunctions such as ‘Resist the third cup of coffee’; ‘Discard all envelops, medicine bottles, last year’s socks / last year’s hopes / Tie every guilt around your ankle.’ The figures are often dressed in cartoon-like costumes with at its centre, the Sibyl, the riveting dancer Teresa Phuti Mojela, sinuously twisting on a central platform, casting her shadow over the enigmatic and sometimes terrifying text: ‘Let them think I am a tree / or the shadow of a tree / a doubt / a shadow of a doubt / There will be no epiphany.’

‘Rorschach’ is a particularly striking scene where shadows play against a curtain as objects morph into new objects without any immediate sense, but later a coherent pattern seems to emerge just as the leaves of the Sibyl become the pages in Dante’s Divine Comedy. It builds to a form of climax as the evocative main male vocalist, Xolisile Bongwana, sings of death’s inevitability:

You know what will happen

Though you cannot predict it

The foolish heart that would love

The wise heart that would forget

You will be led away at dawn

Almost don’t tremble

Evasive action meets the vital strike

The multi-talented creative team includes: Žana Marović (editing and compositing); Greta Goiris (costume design); Sabine Theunissen (set design); Urs Schönebaum (lighting design); Gavan Eckhart (sound engineering); Duško Marović (cinematography); and Kim Gunning (video orchestration). There is no narrative arc in the work, and the opera ends on a note of resignation, perhaps even acceptance, as the principal female vocalist, Zandile Hlatshwayo, seemingly singing of the futility of it all, brings a plangent, searingly haunting tone to the words:

Day will break more than once

All so different from what you expected.

But Joy will overtake Fear.

No protection but each other’s limbs

Love will paralyse the joints

The smell of the neck

15 minutes on the soft shoulder

Something has been postponed.

TO WHAT END?

Sibyl is a work that cannot be fully absorbed in one sitting; it provokes a variety of emotional and intellectual responses, many to be recollected later in tranquillity. There are many moments in Sibyl which have immediate and tragic contemporary references (as in the epigraph quoted above).

Kentridge, a force of nature, gathers superbly talented performers around himself like a giftedly benign Pied Piper. Sibyl is often baffling and obscure, but then, turning on its axis, flashes of deep insight, revelation, beauty and intense longing emerge, Kentridge inexorably drawing one into his capacious and unique world view; perhaps best expressed in a text from the opera: ‘You will (for 20 minutes) have great happiness. It is not enough (but it is not nothing).’ As the world watches with great interest the Artificial Intelligence meeting of the most prominent ‘Tech Bros’ and several governments currently underway in Bletchley in the United Kingdom – appropriate venue! – Kentridge has a succinct yet potent message from the Sibyl:‘Starve the Algorithm!’ It is the shared humanity that emerges from these virtuosic performances, which cannot be replaced by AI, that will linger in the consciousness of the audience. Sibyl is a superbly fitting finale to the month-long Opera House fiftieth birthday celebrations. One is immensely richer for the experience.

Sibyl (Sydney Opera House) continues at the Joan Sutherland Theatre until 4 November 2023. Performance attended: 2 November.