- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Custom Article Title: Twelfth Night

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Twelfth Night

- Article Subtitle: Shakespeare’s topsy-turvy play twists again

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night is a perennial favourite on the Shakespeare calendar (pun intended). The twelfth night of Christmas celebrations was the olden-day version of New Year’s Eve, not because it was the last day of the year but because it was the last day of festivities, with everything returning to normal after the hangover. As such, it was celebrated as a topsy-turvy night where homeowners would play servant to their servants and bring them gifts, with much frivolity and goodwill – a bit like the boss getting pissed at the staff party.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

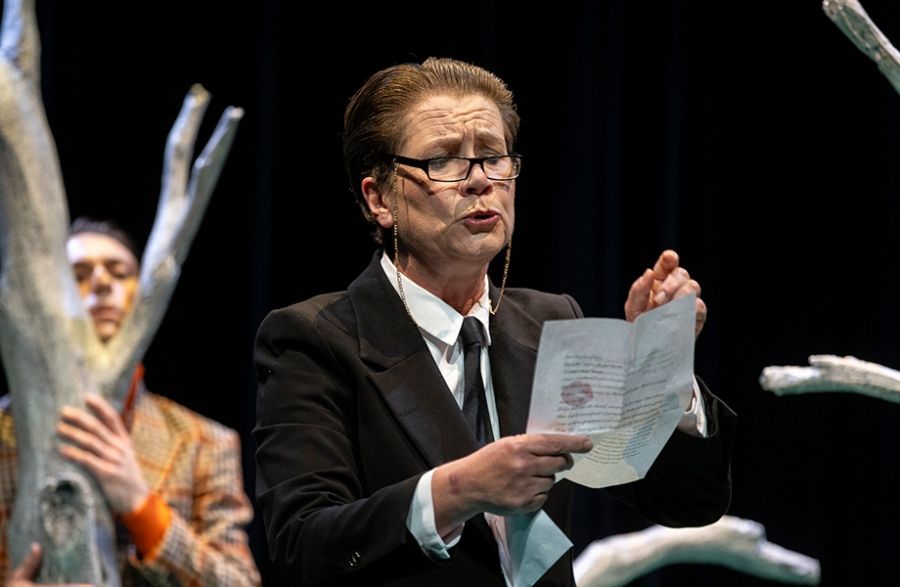

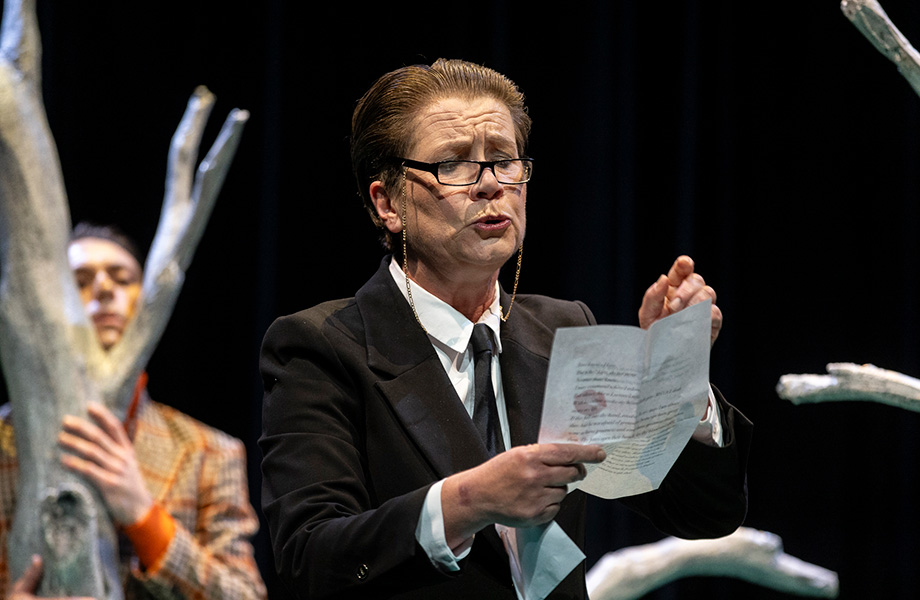

- Article Hero Image Caption: Jane Montgomery Griffiths as Malvolia (photograph by Brett Boardman).

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Jane Montgomery Griffiths as Malvolia (photograph by Brett Boardman).

- Production Company: Bell Shakespeare

The play is also famous for its orchestrated gulling of the servant Malvolio, tricked into wearing bright yellow stockings to impress his boss, Olivia, under the mistaken belief that she fancies him. One would think the play, which is considered one of Shakespeare’s finest and maturest comedies, could hardly sustain anymore twisting.

Bell Shakesepare’s new Twelfth Night, directed by Heather Fairbairn, opens with a set centred around a petrified tree and an array of orange lifebuoy rings (designed by Charles Davis, with lights by Verity Hampson). This captures the initial shipwrecking of Viola in Illyria but seems jarringly ‘out of place’ for the remainder of the action, so famously set within Olivia’s downstairs kitchen and Orsino’s estate. Twelfth Night is simultaneously a sitcom, a romcom, and a musical comedy (containing many songs and interludes), so the presence of a piano is a wonderful ploy, but audiences may get the impression the play is about a beach party. Despite some robust performances, the actors find seats at the sides of the stage to await their next entrance, and when combined with a sheer plastic curtain at rear, both concealing and showing a range of green plants that aren’t used until the final sequence, the energy on stage is often quite static.

Ursula Mills, Isabel Burton, Tomáš Kantor, Chrissy Mae, Garth Holcombe and Alfie Gledhill in Twelfth Night (photograph by Brett Boardman).

Ursula Mills, Isabel Burton, Tomáš Kantor, Chrissy Mae, Garth Holcombe and Alfie Gledhill in Twelfth Night (photograph by Brett Boardman).

The play’s action is all but stage-managed by Olivia’s jester, Feste, played salaciously and sardonically by Tomáš Kantor, who is given almost as much camp licence to run the show as Frank-N-Furter in The Rocky Horror Picture Show, though he’s more nuanced than that. Kantor’s flair seems to borrow from Marc Bolan’s rock and roll playfulness in T-Rex, if not a touch of Red Symonds from Skyhooks and the wryness of Tim Minchin when singing at the piano, strutting about in a pair of cherry-coloured heels that would make Dorothy envious, and all this rounded off with an Elizabethan ruff to present an updated Feste with just enough room to contain Kantor’s flamboyancy.

The comic duo of Olivia’s kinsmen Sir Toby Belch and his carousing companion, Sir Andrew Aguecheek, are shaped with a stroke of genius by director and performers. Keith Agius strikes a perfect note as a merry kilt-wearing Scotsman (though with only one memorable belch). He is paired superbly with Mike Howlett’s fastidious and camp, twinkle-toed, and mock-ballet-dancing Aguecheek in a fox-orange turtleneck and tailored tartan suit. Howlett’s physical gags ensure that he is constantly milking the laughs while staying in character; a bit like Cary Grant, who was trained in vaudeville and was always falling over furniture in his films. The pair create an ‘Odd Couple’ dynamic, where each fuels the comedy of the other, with Agius holding ground as the comic foil against which Howlett’s metal is permitted to shine with fawning vivacity (he steals the show, just a little).

So multifaceted is the play that its prospects for command performances have variously been availed by the roles of Viola, Sir Toby, Feste, or Malvolio. Jane Montgomery Griffiths brings a command performance as Olivia’s steward, a female ‘Malvolia’. Her rigid and upright butlering, staring down her nose at Cesario and the debauched Sir Toby, has a touch of John Cleese in its control. The discoveries she thinks she makes, while reading the letters that will ultimately dupe her, created a comic momentum that drew a laughing ovation from the audience. Unfortunately, this comic control was a little overdone with the yellow stockings, which under Fairbairn’s direction, have been accentuated to the extreme of becoming a yellow body suit. This proves the difference between a cheap laugh and a delightful one. You may win laughs from the groundlings (for the spectacle), but it seems too indecorous, even for comedy. Shakespeare’s comedies aim to delight, thus generating a sense of social warmth that becomes the true ‘take-home’ for audiences. The rhetoric Shakespeare was trained in was designed ‘to teach, to delight and to move’, so this element of delight is more important than spectacle. Having Malvolia peacocking about in yellow stockings to impress the countess is one thing, but wearing a yellow gimp suit is quite another, and seems more reminiscent of Griffith’s role in Titus Andronicus (Bell Shakespeare, 2019) than something in tune with Shakespeare’s comedy.

Some of these jarring touches create a type of bricolage of camp colour when set against the more normative costumes of Illyria (also by Charles Davis). The play becomes genuinely confusing, rather than comically confusing. The director’s notes reveal that a non-specific ‘nowhere place’ was envisgaged, with ‘simultaneous onstage and offstage worlds’, but ‘nowhere’ seems too ungraspable for the theatre, or at least a bit too Beckettian for a Shakespeare crowd. Further confusion arose when the play began with a female Viola (Isabel Burton), then switched to a male actor (Alfie Gledhill) playing a female Viola, as it seemed, before the female Burton returned as Viola’s male twin Sebastian. This additional gender-bending may have helped the show culminate in more diverse same-sex pairings at the end, but at what cost, when things become confusing? The pleasure of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night comes through its untwisting. Further twisting, as they say, seems only to lose the plot.

Twelfth Night (Bell Shakespeare) continues at the Sydney Opera House until 19 November 2023. Performance attended: 26 October.