- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Opera

- Custom Article Title: Die Frau ohne Schatten (★★★★) and Tosca (★★ ½)

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Die Frau ohne Schatten (★★★★) and Tosca (★★ ½)

- Article Subtitle: A fortnight of music and more in the Austrian capital

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The ABR/Academy Travel Vienna tour, now drawing to a close, has revealed some of the riches in this monumental city – the architecture, the art collections (especially the mighty Kunsthistorisches Museum and the brilliant, newish Leopold Museum, with its host of Schieles and Klimts), Emperor Franz Joseph’s Ringstrasse, the general ambience of the city, not to mention the Kardinalschnitte at Gerstner Konditorei.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Die Frau ohne Schatten © Wiener Staatsoper (photograph by Michael Pöhn).

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Die Frau ohne Schatten © Wiener Staatsoper (photograph by Michael Pöhn).

Earlier, on 14 October, we sat further back, in the balcony of the Musikverein, for an unusual pairing from Concentus Musicus Wien: Mozart’s Symphony in E major, K 543 and Haydn’s Theresienmesse, a mass in B-flat major named after the Empress Maria Theresa. This was a welcome opportunity to hear a work rarely performed in Australia. The male choristers and the Vienna Boys’ Choir sang beautifully. Of the four soloists, German soprano Nikola Hillebrand and local baritone Christoph Filler stood out. Stefan Gottfried conducted.

Jaap van Zweden conducted the Wiener Symphoniker at the Wiener Konzerthaus (22 October), a vast, gilt-laden hall with an equally lambent acoustic. The soloist was the Dutch violinist Simone Lamsma, past winner of the Benjamin Britten International Violin Competition. She played Britten’s Violin Concerto, first performed in 1940 then frequently revised by Britten. It was an inspired account of this angular, almost convulsive work. Then van Zweden – Music Director of the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic – led a triumphal performance of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, taken almost dangerously fast, with virtuosic playing right across the orchestra, right down to the piccolo at the end. Again, the sound in the Konzerthaus made this very familiar symphony seem fresh and urgent.

With pellucid acoustics of this kind, it’s little wonder the Viennese seem to attend a concert every other night. It does induce a certain despondency in those returning to Melbourne’s cavernous, unresonant Hamer Hall.

Margarete Wallmann’s production of Tosca is rightly celebrated, not just because it has remained in the Vienna State Opera’s repertory since 1958 – unusual longevity for any opera production. Wallmann – dancer, choreographer, director, stage designer, dance teacher – had had a long association with the Wiener Staatsoper when it dismissed her in 1938 because of her Jewish heritage. Wallmann lived in Buenos Aires until the end of the war and eventually renewed her association with the opera house on the Ring after its reopening in 1955. Followed a succession of major productions: La forza del destino (1960), Turandot (1961, with Birgit Nilsson), Don Carlo (1961) – preceded, famously, by Tosca. Many of the world’s finest singers have appeared in this production. Renata Tebaldi was the first Tosca, Herbert von Karajan her conductor. Christopher Menz – leader of the ABR tour – was here in 1989 when Plácido Domingo sang Cavaradossi, which prompted one of the Spaniard’s epic Viennese curtain calls.

The performance we saw (15 October) was underwhelming, not helped by ponderous conducting from Israel-American Yoel Gamzou, who seemed intent on indulging his singers and the audience’s reflexive yen for ovations, at great cost to the energy and integrity of this vivid score.

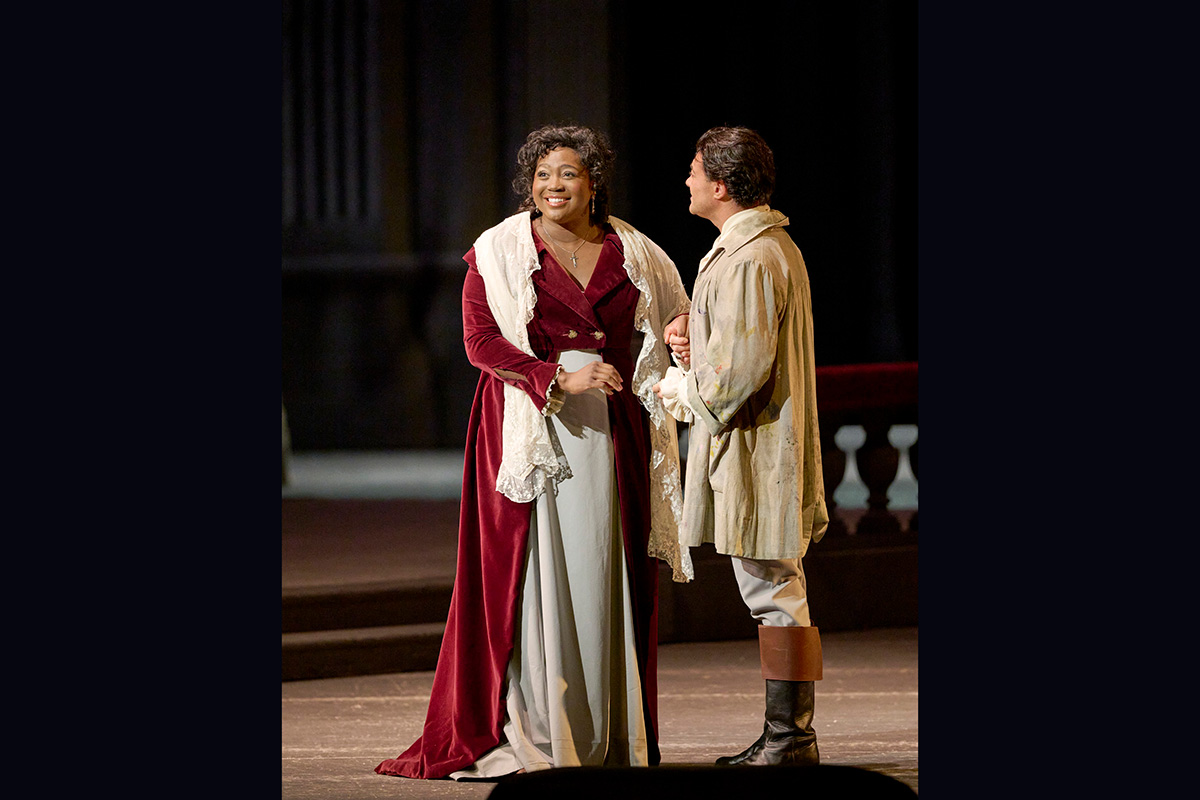

Angel Blue – acclaimed for her performances at the Metropolitan Opera, especially Bess in Gershwin’s opera – seemed uncomfortable, even wrongly cast, as Floria Tosca. She lacks the brittle hauteur of Puccini’s diva, with whom Scarpia, Rome’s Chief of Police, is creepily obsessed. Blue’s attempts at winsomeness in the scene with Cavaradossi in Act One were awkward, and there was little rapport between the lovers. The direction was scant, and the lighting all over the place – though it never landed on Angel Blue, a shadowy figure for much of the night. Blue’s tone is pleasant, and ‘Vissi d’arte’ was handsomely sung, but comparisons with her great compatriot Leontyne Price, which have been made, are exaggerated.

Angel Blue as Tosca and Vittorio Grigolo as Mario Cavaradossi © Wiener Staatsoper (photograph by Michael Pöhn).

Angel Blue as Tosca and Vittorio Grigolo as Mario Cavaradossi © Wiener Staatsoper (photograph by Michael Pöhn).

Vittorio Grigolo – back in favour in certain houses after his excesses – was a popular Cavaradossi with sections of the audience. His best singing (hushed, sweet-toned) came during the two exquisite love duets with Tosca, but too often Grigolo (standing on his toes for dramatic thrust) was determined to hold the high notes forever, and like many a Cavaradossi before him he approached many of them from below. Grigolo clearly loves this opera (he sang the small role of the Shepherd when he was thirteen), but his boisterous attempts during the curtain calls to whip up the audience like a football crowd were vulgar in the extreme.

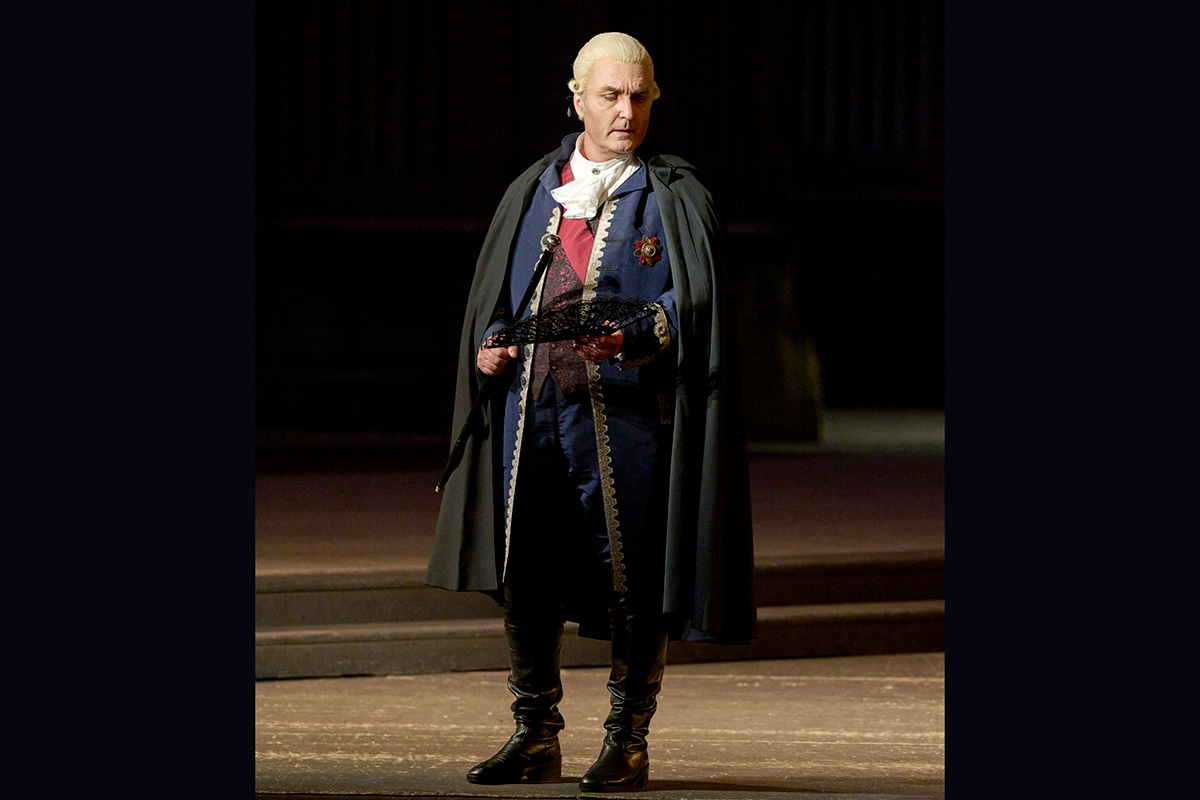

Ludovic Tézier as Baron Scarpia in Tosca (© Wiener Staatsoper and photograph by Michael Pöhn).

Ludovic Tézier as Baron Scarpia in Tosca (© Wiener Staatsoper and photograph by Michael Pöhn).

Best of all was Ludovic Tézier. What a time the French baritone is having. ABR Arts last heard him in Sydney, two months ago, when he stole the show as Barnaba in a concert version of La Giocond . Tézier has been busy in Vienna. Ten days ago, he earned a huge ovation as Germont in La Traviata, and in coming days he will sing Iago here opposite Jonas Kaufmann’s Otello. Germont, Scarpia, Iago within a fortnight: what a feat for any baritone.

Tézier sang beautifully in Scarpia’s two acts, especially the first, when Scarpia pours poison in Tosca’s ear then leads the mighty Te Deum that ends the act. The repeated, loaded ‘Va, Tosca’ cut through the often-overloud orchestra. What a thrilling voice it is. He brought real stagecraft and presence to the role, though the want of direction in Act Two – and Angel Blue’s uneasiness as Tosca – robbed their great scene of its usual drama.

Without a doubt, the operatic highlight was Richard Strauss’s Die Frau ohne Schatten (21 October). While a regular feature in European opera houses, Strauss’s masterpiece has only been presented once in Australia. This was during Leo Schofield’s 1996 Melbourne Arts Festival, when that festival took opera seriously, like every other arts festival worth its salt.

What a grand occasion that was, with John Cox’s production and David Hockney’s sets, Simone Young conducting the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra in the State Theatre, and a memorable cast including Lisa Gasteen, Janis Martin, and Reinhold Runkel.

Vincent Huguet’s production is now four years old. The sets – rocky, adumbral, hard to place historically (though vaguely redolent of the Great War, when the opera was written) – could not be more different from Hockney’s brilliant graphic book-style visions. It opens with an elevated platform that serves as the Empress’s bedroom, then gives way to the jagged tall grey columns that dominate the rest of the opera.

Tomasz Konieczny as Barak © Wiener Staatsoper (photograph by Michael Pöhn).

Tomasz Konieczny as Barak © Wiener Staatsoper (photograph by Michael Pöhn).

The long collaboration of Richard Strauss and Hugo von Hoffmansthal produced several masterpieces, from Elektra (1909) and Der Rosenkavalier (1911) to Intermezzo (1924) and Arabella (1933), but none was more ambitious, or prickly, than Die Frau, for which Hoffmansthal, increasingly reluctant to indulge Strauss’s desire for dramatic clarity and concision, drew on a range of sources including Goethe, The Arabian Nights, and Grimms’ Fairy Tales. The closest equivalent in the operatic repertoire is Mozart’s The Magic Flute, for the principal characters undergo a series of tests in what becomes a kind of fairy tale about the primacy of love and procreation.

Along the way, Strauss and Hoffmansthal – opera’s supreme example of a great composer and an equally important poet-playwright working together for decades (in the process leaving a voluminous correspondence about the creative process) – squabbled and sparred. Strauss called the project ‘Fr-o-ch’ (Frog in German). The two men began work on Die Frau in 1911 and Strauss completed the score in 1917, but the Great War delayed the première until 10 October 1919, at the Vienna State Opera.

Elza van den Heever as the Empress © Wiener Staatsoper (photograph by Michael Pöhn)It is of course the strangest thing, a long, allusive, highly mysterious and symbolic affair that runs for more than four hours. It irritated critics in 1919 and perplexes some listeners still. But it just happens to contain some of the most beautiful music Strauss – or anyone else for that matter – ever composed, especially the orchestral interludes throughout.

Elza van den Heever as the Empress © Wiener Staatsoper (photograph by Michael Pöhn)It is of course the strangest thing, a long, allusive, highly mysterious and symbolic affair that runs for more than four hours. It irritated critics in 1919 and perplexes some listeners still. But it just happens to contain some of the most beautiful music Strauss – or anyone else for that matter – ever composed, especially the orchestral interludes throughout.

Michael Volle, who had made a deep impression as Barak the Dyer a few nights earlier, when the season opened, was indisposed. Tomasz Konioecvny, replacing him, was vocally and dramatically hesitant at first, but improved as the night went on. Strauss, rarely compassionate to tenors, gives the Emperor some fiercely high passages; Andreas Schager was intrepid, ringing, and mostly accurate.

The vocal honours belonged to the women singing the roles of Empress, Nurse, and Dyer’s Wife. Elena Pankratova was fearless and compelling as the Dyer’s Wife, who flirts with infidelity and barrenness of various sorts when the Nurse and Empress seek to beguile her. Pankratova was funny to watch as she responded to their blandishments, only to find her way back to domesticity and contentment with Barak. Tanja Ariane Baumgartner was dramatically and vocally outstanding as the mephistophelean Nurse, who, in this production, is clearly attracted to the Empress. The latter ultimately rejects her in one of the opera’s most poignant moments: ‘Mankind has needs / you cannot understand … / I belong to them, / you are beneath me!’

Elza van den Heever – blonde-wigged, vivid in red all night (the sole shock of colour on stage) – was impressive all night, but her performance in Act Three, when the Empress passes the trial to become human and thus saves the Emperor from being turned into stone, will live in the memory – brilliant singing and acting combined. The South African soprano sings roles like Elsa, Leonore, and Chrysothemis: let us hope we hear her in Australia before long.

Special mention must be made of the lustrous baritone of Clemens Unterreiner, who was almost wasted in the small if critical role of the Messenger.

The evening, however, belonged to Christian Thielemann, who conducted magnificently throughout. He guided Konioecvny all night and drew the finest singing and playing from the other principals, the orchestra, and the chorus alike. Thielemann, very popular in this house, won a massive ovation at the end.