- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

- Custom Article Title: Photography: Real and Imagined

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Photography: Real and Imagined

- Article Subtitle: An ambitious new exhibition at NGV

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Photography has held humanity in its thrall since its nascent years. Celebrated and contested, the photograph is said to have inherent power, making it both a vital, and also dangerous, medium. This exceptional and ambitious new exhibition at the NGV, Photography: Real and Imagined, illuminates why we have an unwavering fascination.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Man Ray Kiki with African mask 1926 National Gallery of Victoria © MAN RAY TRUST / ADAGP, Paris (licensed by Copyright Agency and photograph by Helen Oliver-Skuse / NGV).

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Man Ray Kiki with African mask 1926 National Gallery of Victoria © MAN RAY TRUST / ADAGP, Paris (licensed by Copyright Agency and photograph by Helen Oliver-Skuse / NGV).

- Production Company: National Gallery of Victoria

Featuring 311 photographs from the NGV’s 14,000-strong collection, Photography: Real and Imagined unfolds through twenty-one thematic ‘rooms’: Light, Systems, Surface, Surreal, Narrative, Work, Play, Movement, Display, Things, Studio, Consumption, Skin, Self, Touch, Community, Environment, Place, Built, Conflict, and Death. The exhibition comprises works by creative practice artists, documentary photographers, photojournalists, commercial photographers, people working in advertising and fashion. Display cases exhibit various books, including Harold Cazneaux’s The Bridge Book (1930), William Eggleston’s Guide (1976), Lee Friedlander’s The American Monument (1976), and Tracey Emin’s Exploration of the Soul (1994), emphasising photography’s vast application.

Iconic historical photographers such as Julia Margaret Cameron, Edward Steichen, Alfred Stieglitz, Berenice Abbott, Paul Strand, Dorothea Lange, Max Dupain, and Olive Cotton sit alongside contemporary documentarians and conceptual artists from around the world. Australian David Moore, the first photographer the NGV added to its collection in the late 1960s, also features. Women photographers are prominent. This collection reminds us that photography has been and is used in various ways: as a critical mirror and political tool; a celebration of the extraordinary and the quotidian; a document of evidence and a manipulation of reality. Often boundaries are blurred, warranting a closer look, an educated gaze, an open mind.

The magic begins with ‘Light’. In its early years, to be considered an artform, photography, which was a product of science, was framed as ‘painting with light’. A perfect example of this notion is Australian Pictorialist photographer John Kauffmann’s The Grey Veil, taken in 1919. Kauffmann manipulates light and tonal range to create a luminescent, almost ethereal vision of the Melbourne skyline looking up the Yarra River towards Princes Bridge. Hung nearby is Hungarian László Moholy-Nagy’s Fotogram (1925), a cameraless image that is pure abstraction, an experiment in the darkroom where objects strategically positioned on photographic paper create a picture filled with possibilities. These two photographs point to the plasticity of the art form.

To linger in the light is tempting, but there are twenty more rooms to navigate. In each are magnetic images that act as focal points. The NGVs Senior Curator of Photography Susan Van Wyk tells us that in curating the show she began with ‘the icons of the collection’. She offers May Ray’s Kiki with African Mask

(1926) as an example. ‘It’s a great photograph that represents Paris in the 1920s, the influence of art deco in photography, the fascination with African art objects amongst the avant-garde artists.’ In this single image, there is a complex and nuanced narrative that transcends the objects depicted. Influenced by her lifelong passion for ‘the multiplicity of the medium’, Van Wyk, who has been at the NGV for thirty years, ‘built’ the exhibition thematically rather than chronologically, for the latter would have been ‘too limited’ to capture photography’s ‘multiple histories’.

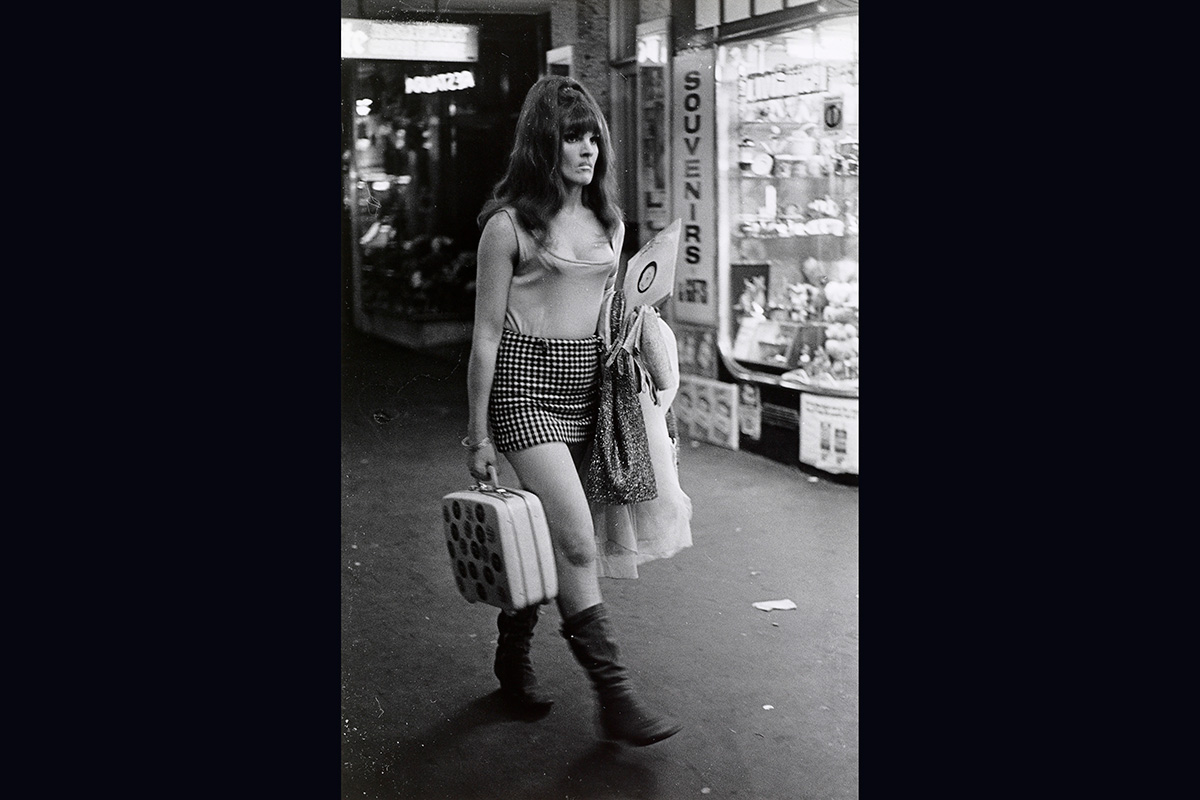

Rennie Ellis Between strips, Kings Cross 1970–71, National Gallery of Victoria © Rennie Ellis Photographic Archive (photograph by Selina Ou / NGV).

Rennie Ellis Between strips, Kings Cross 1970–71, National Gallery of Victoria © Rennie Ellis Photographic Archive (photograph by Selina Ou / NGV).

Photography: Real and Imagined invites the viewer to consider what is truth and to embrace the different ways in which each of the show’s themes can be interpreted and represented. In ‘Community’, Carol Jerrems’ 1976 Sharpies sits with Nan Goldin’s Misty in Sheridan Square, NYC (1991), Donna Bailey’s Lush (2002) and Naomi Hobson’s The God Father (2021). This selection of portraits, both found and posed, reveals how community can be many things. In ‘Play’, the concept of freedom is interrogated through various prisms; David Goldblatt’s apartheid-era The playing fields of Tladi, Soweto, Johannesburg (1972) talks of childhood innocence against a backdrop of political oppression. A grim political narrative also plays out in Chris Steele-Perkins’s Along beach in daylight (1982), shot during the Thatcher years.

In ‘Work’, Brassaï’s Washing Up in a Brothel, Rue Quincampoix (1932) hangs with Rennie Ellis’s Between Strips, Kings Cross (1970–71), reminding us how photography exposes that which is largely unseen. Melbourne photographer David Wadelton’s delightful Richmond hairdresser (1979) depicts four men with almost identical hairstyles having their locks blow-waved. It is both a comical and nostalgic image that affirms how photography literally stops time. In ‘Self’, Australian artist Julie Rrap’s mixed media self-portrait Madonna, at nearly two metres high, is breathtaking. So too is Black South African photographic artist Zanele Muholi’s Ntozkhe II (2016), a self-portrait styled to challenge white ideals of freedom, identity, and pride, from their series Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail the Dark Lioness).

‘Conflict’ features iconic photographs, including Robert Capa’s Death of a Soldier (1932) and Joe Rosenthal’s Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima (1945), both somewhat controversial images that have been the subject of debate as to their veracity. ‘Conflict’ precedes ‘Death’, naturally. These final rooms contain some of the most confronting images. Yet just before the exit the exhibition offers a reprieve, a different perspective on death, with Patrick Pound’s People who look dead but (probably) aren’t (2011–14), a quotidian collection of found snapshots.

In celebration of this milestone exhibition, the NGV has produced a substantial and impressive 420-page tome that allows you to linger with this remarkable collection long after you have left the gallery.

Photography: Real and Imagined continues at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV, Fed Square until 28 January 2024. Entry is free.