- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Opera

- Custom Article Title: Earth. Voice. Body

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Earth. Voice. Body

- Article Subtitle: A trilogy of monodramas on loss

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text: French philosopher and literary critic, Catherine Clément, in her influential and, for some, highly controversial book, L’Opéra ou la Défaite des femmes (Opera, or the Undoing of Women) (1979, trans. 1986), explores many examples throughout the history of the operatic form where the major female characters are inevitably the victims, often dying to the strains of beautiful music.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

.jpg)

- Article Hero Image Caption: Celeste Lazarenko as Elle in La Voix humaine (photograph by Daniel Boud).

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Celeste Lazarenko as Elle in La Voix humaine (photograph by Daniel Boud).

- Production Company: Sydney Chamber Opera

Monodrama is a fluid form, but generally has a single character who sings and speaks accompanied frequently by an instrumental ensemble – occasionally a solo instrument such as a piano – and sometimes utilises a conductor. In the early twentieth century, music was increasingly viewed as capable of externalising psychological states. The foundational monodrama was Arnold Schoenberg’s Erwartung (1909/1924). Taroff maintains that there are three types of monodrama: the first has a single character, such as in Erwartung; the second he terms ‘divided-self Monodrama, depicting the fragmented parts of an individual psyche at war with the individual’; the third is multi-character monodrama where the protagonist’s world view is ‘omnipresent, compelling in their representation of other characters’. There are convergences between song recitals and monodrama, but the song recital generally consists of voice and piano alone, whereas the monodrama usually has an instrumental accompaniment. Monodrama often uses extreme vocal techniques and quasi-modernist operatic vocal strategies.

The centrality of the protagonist’s stream of consciousness in most twentieth-century monodramas generally avoids creating rigidly formal stylistic structures; a fundamental characteristic being the fluidity of form. Monodrama is a theatrical strategy in which the internal struggles of a character are externalised – the figure hovering behind this process, as in so much other twentieth-century cultural practice is, of course, Sigmund Freud. We watch a character coming to some level of understanding of themselves and their place in the world – a subject in the process of formation – despite The New York Times’s Anthony Tommasini’s assertion that when approaching monodrama, ‘it is best to switch off the part of your brain that needs to know what an opera is about’.

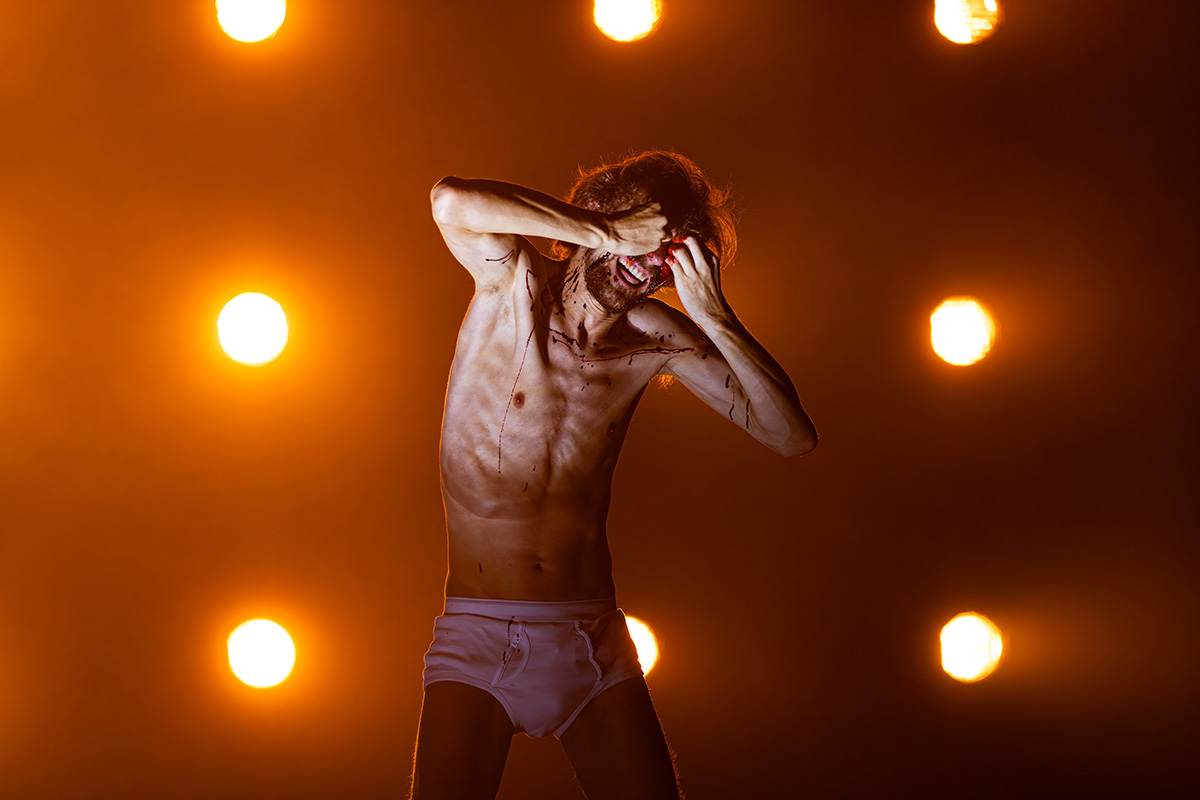

Mitchell Riley in The Shape of the Earth (photograph by Daniel Boud).

Mitchell Riley in The Shape of the Earth (photograph by Daniel Boud).

For a versatile company such as Sydney Chamber Opera, the attractions of monodrama are obvious; primarily, the small scale of production required, with its reduced costs and limited orchestral and vocal forces. Earth. Voice. Body is a trilogy of monodramas: The Shape of the Earth (Jack Symonds, 2018), La voix humaine (Francis Poulenc, 1958), and Quatre Instants (Kaija Saariaho, 2002). All three works are linked by their exploration of loss. ‘I am a spirit splintered into light,’ sings the male protagonist in The Shape of the Earth, baring his tortured psyche to the audience in a work divided into twenty-one fully integrated sections, accompanied by Symonds on the piano, enhanced by Ben Carey’s electronics. With Patrick White’s Voss in the background, and text by Pierce Wilcox, the premise of the work is the situation of a weary traveler, alone in a wilderness, examining his very existence, and attempting to find some meaning through the articulation of these brief song fragments.

Commencing with a slow, tortured, rising vocal glissando, it is immediately apparent that the work is designed with the unique abilities of baritone Mitchell Riley in mind. He has the ability to seamlessly transition from a resonant chest register into an often almost disembodied, androgynous head register without any of the usual vocal ‘gear changes’ this would entail. His often eerie-sounding upper register, usually without vibrato, is very different in tonal quality from the counter tenor voice. He also brings a wide range of extreme vocal strategies, including some florid, quasi-baroque gestures and huge vocal leaps, to the work as well – they don’t teach you these techniques at the Conservatorium! However, he retains a beauty of tone in his natural baritone register.

Allied to these astounding vocal qualities, Riley displays an astounding physical litheness and pliability that complements the kaleidoscopic music with its abrupt changes of mood, tempo, and texture. Symonds’s masterful piano playing gives full sonority to this uncompromising, highly demanding, but always fascinating and often very beautiful score. It is a widely varying and intensely virtuosic piano part, often enhanced by mysterious and evocative electronic sounds creating an orchestral ambience. There are occasional, well-disguised musical quotations, which adds a whimsical aspect to the music. There is no real narrative trajectory in the work, but moments of intense anguish, triumph, disdain, and a myriad of other fleeting emotions. The production is directed by Alexander Berlage on a simple, circular reflecting stage with set and costume designs for all three works by Alexander Lew. Berlage’s lighting design is moody and atmospheric.

Probably the best known, most performed and enduring of all monodramas in the current repertoire is La Voix humaine for voice and orchestra, based on a play by Jean Cocteau (1889 –1963), and written for the soprano Denise Duval, whom Francis Poulenc (1899–1963) described as his ‘co-composer’, having resisted pressure from his publisher to have Maria Callas sing the première; Cocteau himself assisted Poulenc for the first performance. Poulenc did not want the work performed with piano accompaniment, but his niece, Rosine Seringe, sanctioned a piano reduction after Poulenc’s death; a version which is frequently performed. La Voix humaine has been a vehicle for many great sopranos, including Magda Olivera, Renata Scotto, Julia Migenes, and Carole Farley.

The work is sometimes embraced by singers approaching the culmination of a distinguished career, desiring to make a final vocal and dramatic statement, but this certainly is not the case with Celeste Lazarenko, who brought a vocal freshness and plangent beauty of tone to this work, consisting of a series of interrupted telephone calls in which the protagonist, ‘Elle’, through a series of conversations with her ex-lover, realises that he has moved on, and with growing despair and desperation reveals that she attempted suicide the previous night but was saved by her doctor.

Written at a time of telephone exchanges with eaves-dropping operators, the advent of the mobile phone has fundamentally changed the dynamics of this situation, although the frequent interruptions to the calls may seem familiar. Lazarenko skilfully negotiated the fractured nature of the text and music, creating a believable and sympathetic character approaching the end of her resources. The direction is by Clemence Williams, who resists a purely naturalistic interpretation of the work. A bare stage has a blood-red, old-fashioned telephone at the centre, and what appears to be a shrouded couch behind it. This is later amusingly revealed to be a giant red telephone receiver, which the protagonist manoeuvres around the stage as the drama unfolds.

Emily Edmonds in Quatre Instants (photograph by Daniel Boud).

Emily Edmonds in Quatre Instants (photograph by Daniel Boud).

The final work, Quatre Instants, is a song cycle rather than a monodrama, by the outstanding, but sadly recently deceased Finnish composer, Kaija Saariaho (1952–2023), with a French text by Amin Maalouf. Saariaho enjoyed a highly successful career, excelling in many different genres, including the acclaimed opera, L’Amour de loin (Love from Afar), in 2000 – the first opera by a female composer presented at the Metropolitan Opera (2016) since Ethyl Smyth’s Der Wald (The Forest) in 1903. Quatre Instants has four movements, reflecting various dimensions of love underpinning a stormy relationship; the dominant elements being longing, desire, pain, and consummation. It has a restless, glittering piano accompaniment, which again showcased Symonds’s pianistic facility in these widely contrasting contemporary works. Mezzo Emily Edmonds brings a supple, creamy tone with crisp articulation of the text to this striking work. She convincingly conveyed the shifting emotional contours of this twenty-minute vocally demanding work, revealing a gleaming top register and tonal warmth throughout. Clemence Williams directs this work as well, highlighting the dominant aspect of loss, with the simply dressed protagonist, as she gives voice to her emotions, manipulating a large plank of wood which begins to gradually revolve in the mist-shrouded centre of the stage – perhaps a symbolic clock face indicating the passing of time and loss, and bringing a sense of completion to this well-designed program.

Earth. Voice. Body is a challenging but rewarding evening for the audience. Sydney Chamber Opera continues to push the generic boundaries of the operatic art form, offering an important contemporary perspective on the possibilities of opera outside the comfortable mainstream. Richard Meale and David Malouf’s Voss (1986) looms large in Australian opera, but its importance, and the role of opera in general, is questioned in Symonds’s monodrama, and indirectly in the interrogation of the Poulenc and Saariaho works. Symonds notes: ‘To make this kind of work in Australia now requires a loving skepticism of the idea of Romantic, European ambition and an unflinching desire to try to understand how it became a dominant force in 19th and 20th century culture.’ The Australian operatic scene is enriched by the innovation, flair, and, indeed, unflinching artistic courage, of Sydney Chamber Opera.

Earth. Voice. Body (Sydney Chamber Opera) was performed on 28 September 2023 at Carriageworks. It continues until October 7.