- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Custom Article Title: The Chairs

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Chairs

- Article Subtitle: Words words words

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The French-Romanian playwright Eugène Ionesco’s ambivalent attitude towards the power, even the usefulness, of language played out throughout his career. Speaking of Jean-Paul Sartre, Ionesco (1909–94) said that he ‘wrote an important book called Words and there he noticed that he had talked too much all his life. That words are not saying anything.’ Later, Ionesco claimed ‘[w]ords no longer demonstrate anything. Words just chatter. Words are escapism. Words prevent the utterance of silence.’

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

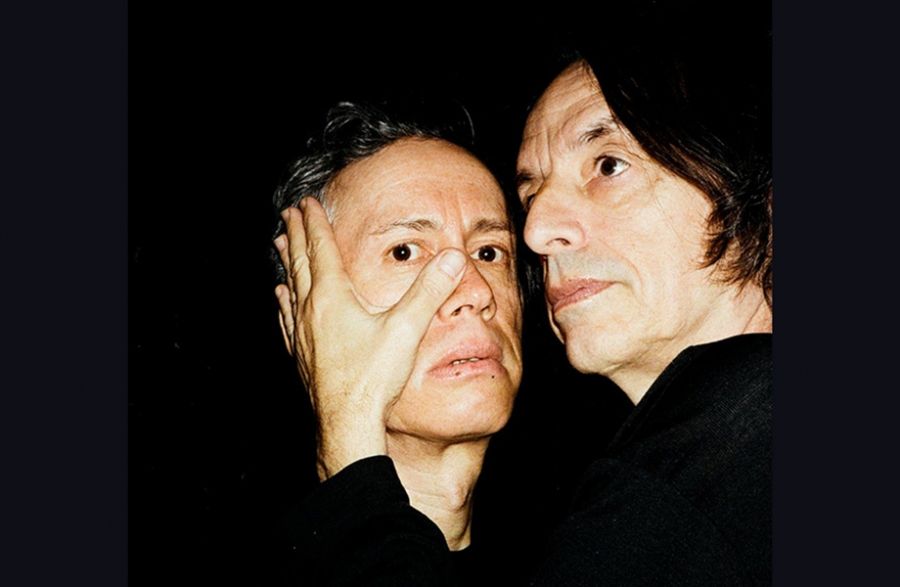

- Article Hero Image Caption: iOTA and Paul Capsis in The Chairs (photograph by Jasmin Simmons).

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): iOTA and Paul Capsis in The Chairs (photograph by Jasmin Simmons).

- Production Company: Red Line Productions

This repudiation of language did not prevent Ionesco from writing countless essays, an autobiography, and several plays. While his fellow absurdist Samuel Beckett gradually moved towards silence in his works, Ionesco became more verbose. But the words his characters utter have little effect. In The Killer (1958), Ionescu’s everyman, Berenger, is faced with a homicidal maniac. In a lengthy, bravura speech, he uses every kind of argument to make the giggling grotesque desist. But his desperate platitudes are useless and he ends up another of the killer’s victims.

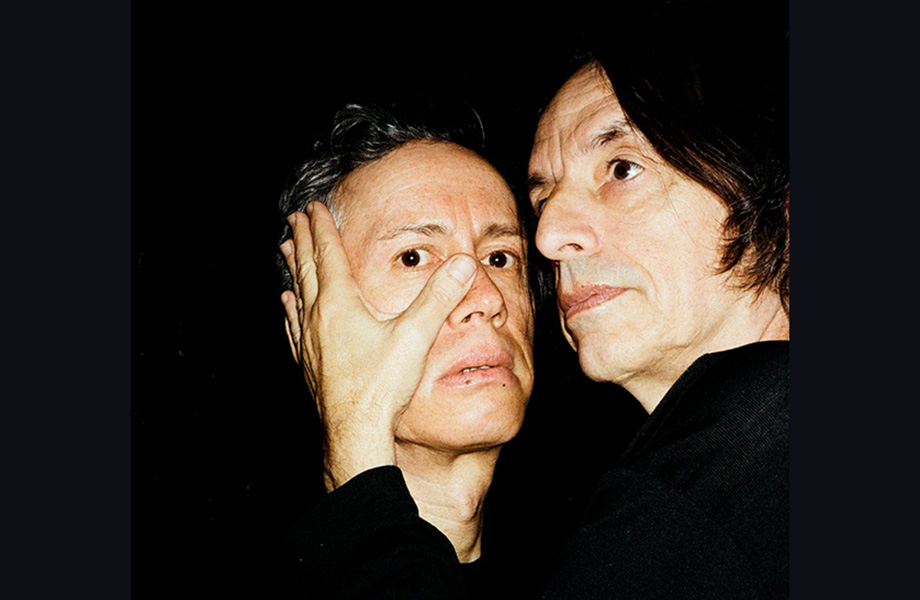

iOTA and Paul Capsis (photograph by Phil Erbacher).

iOTA and Paul Capsis (photograph by Phil Erbacher).

The Chairs (1952) is an early exploration of this theme. In a gloomy tower surrounded by water, an ancient couple reminisce and bicker as they prepare for the appearance of guests who will come to hear the husband’s message to mankind, a message he claims will save the world. As the guests – invisible to us in the audience but real to them – arrive, chairs are dragged out and the couple become more frantic as the crowd grows and the Orator, who will present the message, delays his arrival. Eventually, to the couple’s ecstatic relief, he appears but, this being Ionesco, the message remains a mystery.

In our post-truth world, flooded with increasingly insane conspiracy theories, climate change denialists, and blatant political lies, Ionesco’s question – do words really any longer have meaning? – has an ominous relevance.

The play’s first production, at the tiny Théâtre Lancry in Paris, though meticulously rehearsed, was a somewhat ad hoc affair, with Ionesco still trying to scrounge chairs from local cafés on the day of the première. At the equally tiny Old Fitz in Sydney, director Gale Edwards and designer Brian Thomson, whose previous excursion into absurdism for Red Line, Krapp’s Last Tape, was a highlight of the 2019 season, have cleverly conquered the logistics of the piece. A red circle is backed by a clutter of untidily stacked chairs leaning against walls that are painted with large-headed stick figures who will become standing members of the capacity crowd. In a corner and out of focus, a screen depicts the stage action. Even in this remote location, the couple are being observed.

There are two ways of presenting the couple. Either they can be played naturalistically, as a recognisable old pair in a surreal situation, or you can abandon any attempt at naturalism and present them as expressionistic grotesques. When you cast Paul Capsis and iOTA in the roles, it is obvious in which direction you want to go. What makes this production so poignant is that, even at their most farcical, Capsis and iOTA still manage to find the humanity in their characters.

In this gender-fluid production, Capsis plays the character Ionesco calls the old woman and the old man calls Semiramis. Capsis is hilarious as he beats off the advances of one guest and races off another. As the crowd grows, he scurries around maniacally, dragging in yet more chairs and eventually selling programs and the odd ice cream. But Capsis never lets us forget that this is being done out of the devotion and belief Semiramis has for her husband. Her constant proposition that he could have been a great success if things had turned out differently comes across as both balm and irritation to her conflicted spouse.

iOTA’s old man is a more complicated character. Convinced that he has the answer to the world’s problems, he can still be reduced to a weeping wreck calling for his mother. He is both steely and vulnerable. At one point, as he rants about the world he wants to create, one can imagine the sort of leader he would have become if given the chance. He has the self-belief and narcissism of the born autocrat.

Angela Doherty’s costumes morph from institutional burlap to somewhat tacky finery as the pair ready themselves for the occasion. Benjamin Brockman’s lighting and Zac Saric’s sound design work effectively.

Given the limitations of the Old Fitz stage, compromise was inevitable, but Edward’s rejigged ending works brilliantly and she remains faithful to Ionesco by having the audience sit quietly as we hear the ghost audience leave. Which gave this reviewer a chance to contemplate his next outing with words.

P.S. Red Line, could you please reassemble the team for a production of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi.

The Chairs (Red Line Productions) continues at the Old Fitz Theatre until 15 October 2023. Performance attended: 9 September.