- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: Rembrandt: True to Life

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Rembrandt: True to Life

- Article Subtitle: Etched with feeling

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Unlike his compatriot Jan Vermeer, Rembrandt van Rijn was never forgotten. Like a Beethoven of visual art, he has always been a beacon and has always inspired later artists. Famous for his biblical storytelling on a symphonic scale, he was also a supreme portraitist and master of the self-portrait in oils (he made more than forty). Public familiarity with Rembrandt’s oeuvre in the centuries before photography came from his unmatched mastery of the artist’s print.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

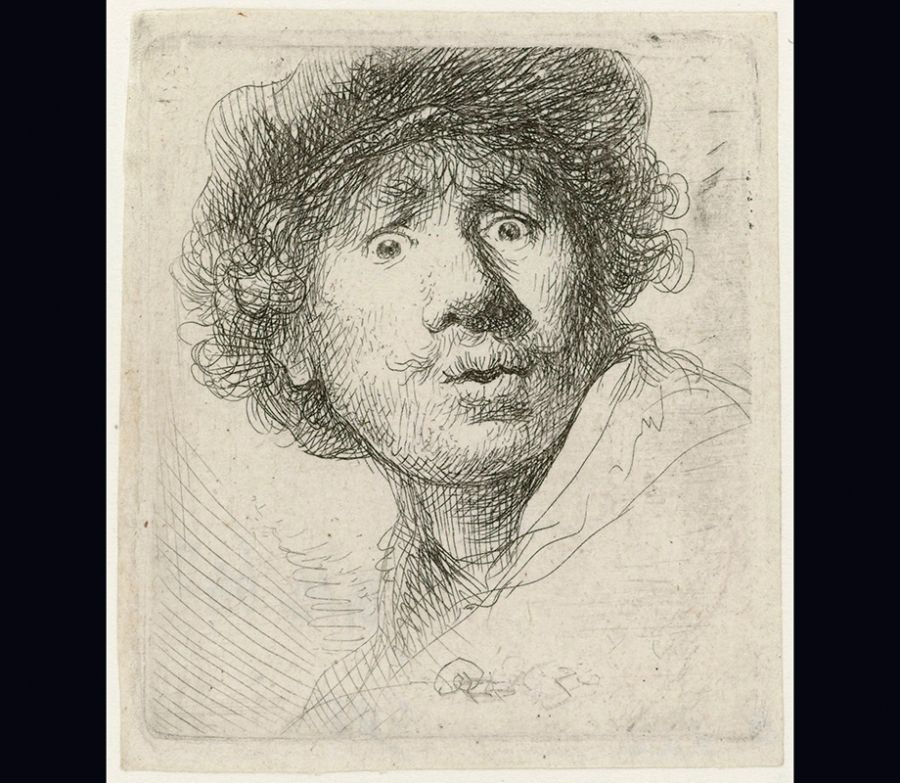

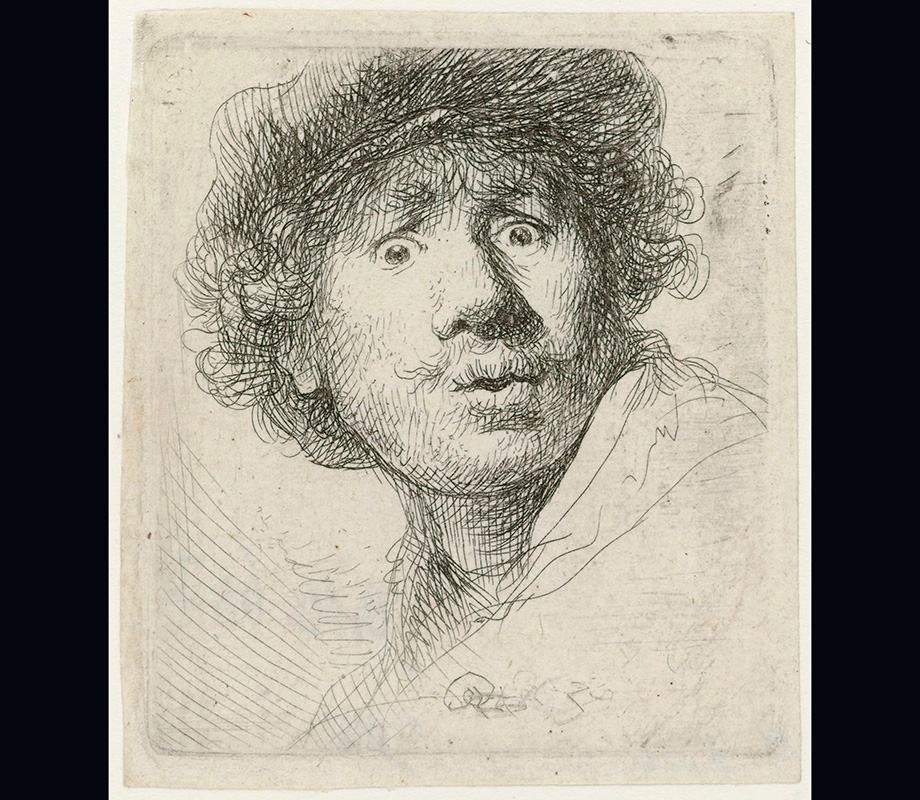

- Article Hero Image Caption: Rembrandt Harmensz, Self-portrait in a cap, wide-eyed and open-mouthed, 1630 (photograph by Rijksmuseum and courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria).

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Rembrandt Harmensz, Self-portrait in a cap, wide-eyed and open-mouthed, 1630 (photograph by Rijksmuseum and courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria).

As with Dürer, the National Gallery of Victoria holds a comprehensive collection of Rembrandt’s graphic work, and about once in a generation the public gets to enjoy it in full. In 1891, the embryonic NGV had the foresight to buy eleven major prints from a British connoisseur (at a time when the Sydney gallery preferred salon potboilers that quickly dated). Between the wars, Melbourne’s munificent Felton Bequest kicked in with the purchase of three oils and dozens more prints. Fifty-three etchings arrived in one fell swoop in 1933, bought from the remarkable Australian peintre-graveur Lionel Lindsay, a devotee of Rembrandt, whose sell-out 1927 London sale of Spanish scenes enabled his feverish collecting.

For children of the digital and televisual age, the fascination of traditional artworks is, as the late Betty Churcher said, ‘that they do not move, they are unchanging’. There is something miraculous about the way a story unfolds in a Rembrandt sheet when viewed from twenty centimetres away. Each line is at the scale of human fingers, a visual fascinator for young and old visitors to Rembrandt – True to Life. I spent two hours in the exhibition, but so did many others: young people from home and abroad who leavened the steady flow of well-dressed bourgeois and scruffier septuagenarians. The exhibition’s very installation produces a euphoric feeling of Gezelligheid – the untranslatable Dutch word that evokes the warmth of familiarity and fellow-feeling that animates Rembrandt’s art.

Rembrandt Harmensz, Man in oriental clothing, 1635 (photograph by Rijksmuseum and courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria).

Rembrandt Harmensz, Man in oriental clothing, 1635 (photograph by Rijksmuseum and courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria).

Curator Dr Petra Kayser has had the walls and ceilings of the several galleries painted very dark brown. The effect of this ‘black cube’ aesthetic (as opposed to the ‘white cube’ of twentieth-century fame) is to promote concentrated looking. Light is low (for works on paper), but adjustable rectangular spotlights are used, giving accuracy to the very edge of the paper. The effect rivals the illuminated screens of an iPhone or a television in a darkened room. It leads to an intensification of looking, to a focus upon the image.

This is in complete contrast to the much-criticised installation poor Bonnard’s ghost endures across the NGV’s great court. In Pierre Bonnard, designed by India Mahdavi (sic) the décor of giant screens – patterned with digital splodges in colours borrowed from Brunetti’s gelato bar – has the opposite effect. These vast expanses of bright pattern leach attention from the images; they scatter and disperse the gaze. It is the opposite of an ‘immersive’ experience (in spite of the superb collection of Bonnard’s works assembled). As if the painter alone were not enough (and the dozen Bonnard monographs on Amazon books prove his standing), giving billing to a decorator seems an insult. The NGV has apparently forgotten the professional farce of 1993 that was its Shell Presents Van Gogh (sic), which garnered international ridicule for allowing the sponsor’s grandstanding.

Rembrandt Harmensz, The Mill 1645–48 (photograph by National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC and courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria).

Rembrandt Harmensz, The Mill 1645–48 (photograph by National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC and courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria).

Picasso (who was obsessed by Rembrandt) said to Paul Klee in 1937, ‘you are the master of the small, and I of the large’. Rembrandt mastered both, from the stamp-sized self-portrait etchings of his youth to his powerful oil The Mill, lent from Washington. Through the admirable wall panels written by Kayser, we learn much of the mysteries of Rembrandt’s printmaking, how he improvised new technical solutions in etching and drypoint. The NGV’s compendious holdings allow Kayser to display paired ‘states’ of several prints, such as The Three Crosses: one brightly geometric, its successor cast in sombre deep shadow. Rembrandt inherited the game of luminous contrasts from Caravaggio, but here he makes it a vehicle for tragic feeling.

There has never been a more penetrating portraitist. The poet Huygens, visiting the studio of the twenty-two-year-old, marvelled that ‘a youth, a Dutchman, a beardless miller, could put so much in one human figure and depict it all!’ Rembrandt was always a champion of the older person, and of the common folk whom he ennobled rather than excluded. On St Kilda Road, he can still show us how to age with grace and integrity.

In one respect this Rembrandt exhibition is unique: it features a room with three large vitrines that embody the ‘Kunst Caemer’ or cabinet of curiosities that Rembrandt assembled during the halcyon years of his success in Amsterdam, then a great mercantile and colonial capital. Kayser is in a unique position to re-imagine his collection of objects, as her 2005 doctorate was on the Kunstkammers of Europe. Using the inventory of Rembrandt’s household (made for his sorry bankruptcy case in 1656), she has borrowed from the Museum of Victoria, the State Library of Victoria, and has drawn on the NGV’s own collection to assemble ‘animals, shells, corals, exotic textiles, Chinese porcelain, Indian Mughal miniatures, Turkish weaponry, helmets, glassware, busts of Greek philosophers … medals and books’. A treat for the eyes and mind, these objects connect the twenty-first-century viewer to Rembrandt’s world in vivid material ways.

The accompanying catalogue, Rembrandt: True to Life (edited by Petra Kayser, NGV Books, $59.95, 258 pp), is a beautiful book. It perfectly marries information and imagery, is easily navigated, and is graced with essays by eight experts from the Netherlands and Germany, as well as four NGV specialists. The book’s footnotes are sprinkled with recent publications in four or five languages, so we can be sure Rembrandt – True to Life brings the very latest in scholarship (including, in Laurie Benson’s essay, on our two great oil paintings, Two Old Men Disputing and Portrait of a White-haired Man). Etching is beautifully served here by fine reproductions, with numerous double-page, close-up spreads, and the Hundred Guilder Print as a frontispiece. Tony Ellwood’s NGV has not stinted in supporting this magnificent album of its collections. The book is a serious contribution to scholarship, and a triumph of dissemination: the NGV working at its very best.

Rembrandt – True to Life continues at the National Gallery of Victoria until 10 September 2023.