- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency

- Article Subtitle: The unflinching gaze of Nan Goldin

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I find myself going to view Nan Goldin’s legendary series of photographs, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, with trepidation. Lying at the heart of these works is a renowned image, Nan after being battered, 1984. Taken by her friend, Suzanne Fletcher, it shows a youthful Goldin with big 1980s hair, dangling silver earrings, a necklace of pale beads. She gazes into the camera, her left eye swollen and bloodshot, her right eye framed by a half-healed bruise.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

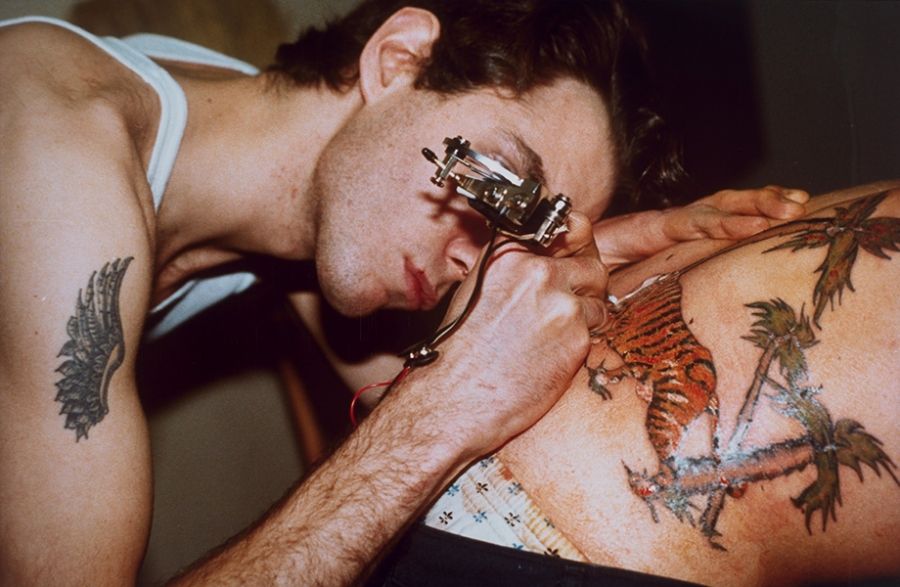

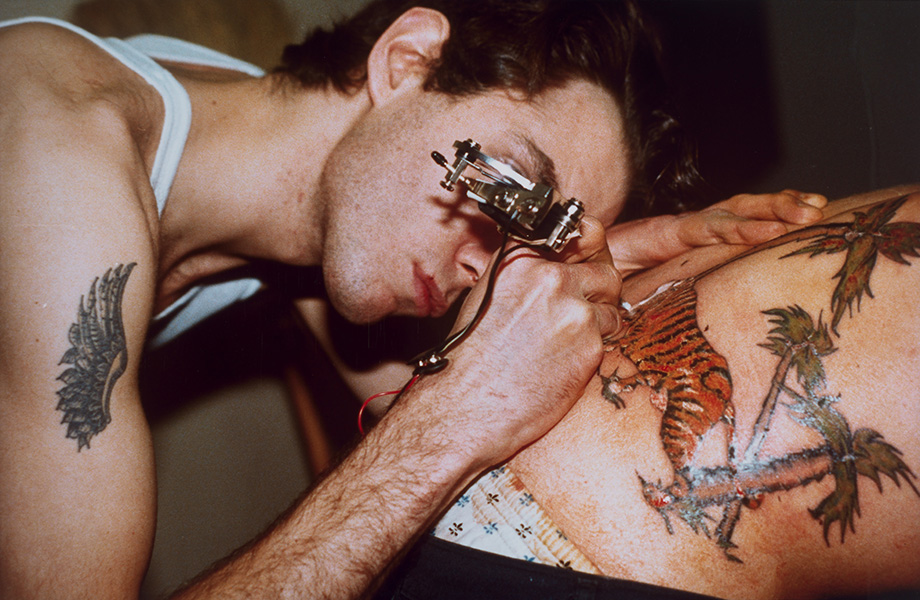

- Article Hero Image Caption: Nan Goldin, Mark tattooing Mark, Boston, 1978 (© Nan Goldin and courtesy of National Gallery of Australia).

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Nan Goldin, Mark tattooing Mark, Boston, 1978 (© Nan Goldin and courtesy of National Gallery of Australia).

‘This kind of truth is usually hidden,’ says curator Anne O’Hehir, gesturing towards dark glasses and concealer makeup. ‘But Goldin puts on the lippy and gets out the camera.’ It was ground-breaking. ‘That kind of imagery was not seen at the time,’ Goldin says in a 2020 interview in Aperture magazine. Women from all over America and Europe came to her and told her their stories.

Nan Goldin, Nan and Brian in bed, New York City, 1983 (© Nan Goldin and courtesy of National Gallery of Australia).

Nan Goldin, Nan and Brian in bed, New York City, 1983 (© Nan Goldin and courtesy of National Gallery of Australia).

American author and social critic bell hooks writes in Talking Back (1989) of violence in intimate relationships and of people – her mother, herself, and several acquaintances – who are only hit once. How do we talk more openly about, recover from, and de-stigmatise ‘being physically abused in singular incidents by someone you love’, she asks. Just as with sustained abuse, there is a shattering of trust, a collapsing of the known world. In facing these questions, both hooks and Goldin refuse to be silenced by shame.

The Ballad, whose title references a song from Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera, began life as a slideshow presented in bars and nightclubs in Manhattan during the late 1970s and 1980s. Slides were cheaper than colour prints, and they allowed for an abundance of images whose sheer proliferation, cinematic quality and narrative allusions meant that the work veered as much towards film as towards any notion of photography as the ‘decisive’ single take. Each slideshow was different, comprised of hundreds of images of the ‘post-punk, creative, queer scene that comprised Nan’s community, her chosen family’ writes O’Hehir in her exhibition essay ‘Nan Goldin’s Lens on Relationships’ (2023). Iterations of The Ballad have been shown at the Whitney Biennal (1985), and at MoMA (2016–17), among others.

Initially, the people in the photographs were also the audience for the work. In the Oscar-nominated documentary All the Beauty and the Bloodshed (2022), Goldin describes an animated collaborative process whereby audience members yelled out responses either in appreciation or to let Nan know if an image was unflattering. She removed images accordingly. Friends also helped her compose a soundtrack for the show. Her purpose, she writes in the 1986 book version of The Ballad, was to endow her chosen family with a ‘strength and beauty’ not even they knew they possessed.

‘Nan’s early images survive a time of sexual life before AIDS and a love of drugs before the wages of addiction had to be paid,’ writes author and interviewer Darryl Pinckney in Aperture. After Brian’s violent outburst, Goldin developed an overpowering fear of men. She left her bar job at Tin Pan Alley and disappeared into her room and the solitude of addiction. When she re-emerged, she discovered that AIDS had moved through her community like war. It was partly AIDS, says O’Hehir, that impelled Goldin’s distillation of the early versions of The Ballad down to the core photographs found in her book. These images have become a historical record of a particular time, ranging across locations – New York, Berlin, London, Mexico – and they have also become a memento to lost friends and lovers.

That the book has never been out of print is testament to Goldin’s contribution to the history of photography, her forging of a new form of intimate, diaristic imagery that pays tribute to her chosen family, created out of the bedrooms, bathrooms, and bars they inhabit together. Goldin is no dispassionate observer. The intimacy of Larry Clark’s Tulsa (1971) series – teenagers shooting up and having sex – was an early influence. She works against the convention of the voyeuristic outsider or what The Met calls the ‘camera’s burrowing eye’ (in reference to an iconic Walker Evans portrait). Instead, Goldin takes the ethnographic premise of ‘participant-observer’ to new levels, making no distinction between her life and her photography. ‘It’s as if my hand were a camera,’ she wrote in 1986, as much a part of her everyday life as talking, eating, or sex. Her camera was just as commonplace, at that time, in her friends’ lives, capturing them naked or semi-clothed in bed, eyes closed in the shower, sprawled on towels at the beach, or masturbating. Historical markers abound: a red telephone with spiral cord, cassette players, a cheeseburger radio, Playboy magazines, a Kathy Acker book on a beach towel, Cyndi Lauper on a dim blue television screen.

Nan Goldin, Twisting at my birthday party, New York City, 1980 (© Nan Goldin and courtesy of National Gallery of Australia).

Nan Goldin, Twisting at my birthday party, New York City, 1980 (© Nan Goldin and courtesy of National Gallery of Australia).

The gritty, erotic quality of the works is undeniable – the soiled soles of feet, a man and woman lying together both wearing white slips, men with men, women with women, people alone, people transitioning, grimy cheap-rent apartments, an empty bed in a brothel. The colour in the Cibachrome prints is rich and saturated: golds and browns of patterned wallpaper; emerald-green op-shop chic of filmmaker Vivienne Dick’s dress, framed by ‘amateurish’ shadows cast by the flash; deep reds of a car interior. Goldin played with these metallic hues at a time when colour was only just beginning to be taken seriously in the photographic world.

Images of edgy glamour show the influence of fashion photographers such as Guy Bourdin and Louise Dahl-Wolfe, and of filmmakers admired by Goldin, including Antonioni, Buñuel, Fellini, Warhol, and others. Actor and writer Cookie Mueller is lit by yellowish film lights, caught in a pensive non-performative moment against the gloom; a pregnant woman in a sequined bikini lies on a stone slab (Rebecca at the Russian Baths, New York City 1985); men in drag picnic by the water, laughing and eating cake (Picnic on the Esplanade, Boston 1973). There are also images of profound sorrow. Suzanne crying, New York City 1985 must be one of the rawest images of grief ever captured, almost as if the camera has strayed too close and too deep.

Throughout runs a perplexing fear, Goldin writes: ‘that men and women are irrevocably strangers to each other, irreconcilably unsuited’. Brian makes numerous appearances (as does Suzanne). Early in the sequence Nan is seated on his knee, clasping him around the neck, smiling, dressed in a 1950s frock. During their early romance, he takes on the aura of a wary James Dean-like figure (dispelled by Nan’s later exposure of his broken, grey teeth or his moody handling of a rifle at a shooting gallery). It takes several viewings before I realise Goldin is wearing similar dropped earrings and pearl-like necklace as those in Nan after being battered. It’s a narrative marker, charting a journey from passion, obsession, love, addictive sex, and the merging of identities to disenchantment and violent separation. When I visited The Ballad, I had just finished reading Jenny Erpenbeck’s novel Kairos (2023 English translation). It too charts this fraught terrain, what Goldin calls ‘the struggle between autonomy and dependency’.

Running beneath Goldin’s work is an even deeper haunting, best understood through All the Beauty, which illuminates Goldin’s early family life (her blood family) with great poignancy: her beloved sister Barbara’s suicide at the age of eighteen, when Nan was eleven; her parents’ suppression of this tragedy, calling it ‘an accident’; the stifling conformity of 1950s suburban America; her mother’s own fragile state, culminating in her rejection of Barbara at Barbara’s time of deepest need; Goldin falling into silence as a teenager, barely speaking above a whisper; her discovery of the camera as voice, as saviour, as a means of connecting with others, as a surrogate for love and sex, and a talisman (says O’Hehir) for survival, both her own and others. Although Goldin doesn’t employ this language herself, her family’s story is recognisable as one of intergenerational trauma – as a child, her mother suffered prolonged sexual abuse. It’s against Barbara’s loss that Goldin declares, in 1986, that she will take charge of telling her own history, so she is not ‘susceptible to anyone else’s version’. ‘Secrets destroy people,’ she says in All the Beauty. Her life’s work from The Ballad onwards, including her recent activism calling the Sackler family to account for their role in the opioid crisis in America, is impelled by these forces: to make ‘real memories’ of loved ones, ‘an invocation of the color, smell, sound, and physical presence, the density and flavour of life’; and to dispel the destructive power of the secret.

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is on at the National Gallery of Australia until 28 January 2024.