- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: Dalíland

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Dalíland

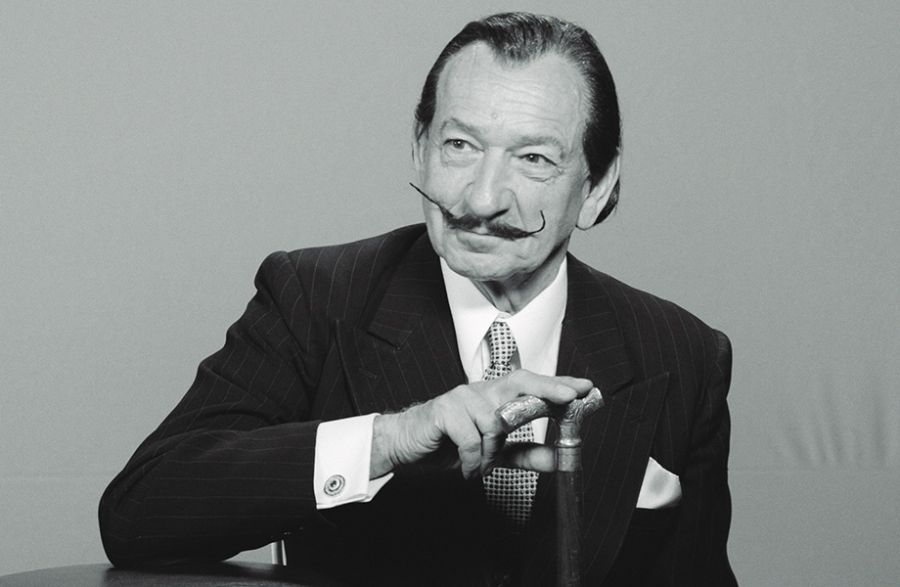

- Article Subtitle: Ben Kingsley as Salvador Dalí

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In January 1957, Salvador Dalí appeared on American television in What’s My Line, a game show featuring a segment in which blindfolded panellists tried to work out the identity of a mystery guest by asking only yes-no questions. Dalí did not make it easy for the panel or the host: he answered ‘yes’ every time, not only to ‘Are you a performer?’ and ‘Would you be considered a leading man?’ but also to ‘Do you have anything to do with sports?’ In his mind, he was famous for absolutely anything and everything.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Ben Kingsley as Salvador Dalí (photograph courtesy of Kismet).

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Ben Kingsley as Salvador Dalí (photograph courtesy of Kismet).

- Production Company: Kismet

This footage is part of a news report on the artist. It is 1985, and a young man is watching television and remembering. We are then taken back to New York in 1974, when this young man, James Linton (Christopher Briney), newly employed as an art gallery assistant, is dispatched to deliver a large sum of money to the artist at the New York hotel where he has been spending several months every year since 1949.

‘Welcome to Dalíland,’ says Dalí’s secretary, Captain Peter Moore (Rupert Graves), as he opens a hotel room door onto a scene of the artist, holding court in a room full of the beautiful, the elegant, the young and the extravagantly dressed. This is his first glimpse of twenty-four-hour party people, Dalí-style. They are part of the entourage with which Dalí surrounds himself, a world in which it seems that the focus is making money and producing art with the minimum of effort.

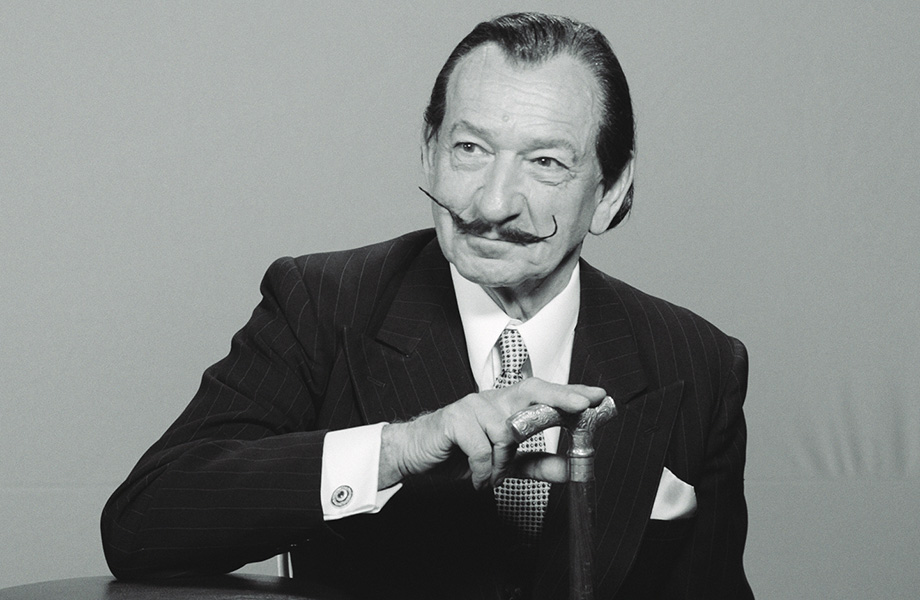

Andreja Pejic, Ben Kingsley and Barbara Sukowa in Dalíland (courtesy of Kismet).

Andreja Pejic, Ben Kingsley and Barbara Sukowa in Dalíland (courtesy of Kismet).

For the wide-eyed James, ‘Dalíland’ is not exactly Wonderland, although it has a capricious queen at its centre: Dalí’s wife, Gala (Barbara Sukowa), who plays the role of a muse, mother and monster in her husband’s life. Dalí asks James to become his assistant: the gallery owner agrees, as long as James focuses on making sure that Dalí produces work in time for the opening of his show, three weeks away.

Harron has explored a legendary figure of the art world at a moment of crisis before, although the outcome and emphasis were very different. Her vivid first feature, I Shot Andy Warhol (1996), which she also co-wrote, is the story of Valerie Solanas, radical feminist and aspiring playwright, who shot Warhol. Dalí and Warhol knew each other, and, as it happens, there is a crossover moment in Harron’s Warhol film, in which Andy mumbles to Solanas that he can’t stop and talk to her, because he is going to a party that Dalí is throwing at the St Regis hotel.

Dalíland – written by Harron’s husband, John C. Walsh – is in some ways a generous vision of its subject, even as it acknowledges his declining reputation, his taste for distraction, his cupidity, his gift for and vulnerability to manipulation, not to mention the more brutal and abusive aspects of his tormented relationship with Gala. He has plenty of enablers and exploiters around him, all of whom rationalise or explain away what they are doing, no matter how dubious.

The central performances are strong. Kingsley, as Dalí, highlights frailty as well as excess; it is a precisely observed rather than extravagant interpretation. As Gala, Sukowa (who began her career in the films of Rainer Werner Fassbinder), brings a contrasting energy, an explosive abruptness and volatility: brief, spiky outbursts of rage, handing out slaps and throwing objects, as well as disconcerting moments of tenderness or reflection.

Dalí and Gala, seventy and eighty respectively, both have an appetite for youth and beauty that affects them in different ways. Gala – who had taken lovers throughout the marriage – had become besotted with Jeff Fenholt (Zachary Nachbar-Seckel), a young singer who was appearing in Jesus Christ Superstar on Broadway. She is spending a fortune on him, partly in the belief that he has an extraordinary career ahead of him. ‘His songs will change the world,’ she says confidently; it’s as if she has found her new muse project. This infatuation irks and distresses Dalí, but she is still available to manage him when she’s needed, subject to negotiation.

The film also seeks to show us, in somewhat awkward fashion, Dalí and Gali in the bloom of their youth: their first meeting; the time when Dalí painted a key work; and a moment when Dalí realised, as he tells James, that he had found his other half. In these scenes of flashback-recollection, as described by Dalí, the younger pair are played by Ezra Miller and Avital Lvova.

Unfortunately, these brief diversions are heavy-handed; worst of all is a literally cheesy scene in which Dalí is inspired to paint what is presumably his 1931 The Persistence of Memory, as implied by point-of-view shots of a melting camembert and a wall clock. There are no actual examples of Dalí’s work in the film, but this is not the way to manage its absence or suggest its presence.

The figure of James also weighs heavily on the film, despite his insubstantial nature. Unlike many of the characters who appear, often fleetingly, in Dalíland, James is fictional. A composite, perhaps, of handsome young men who were in the Dalí orbit. He starts out as a naïve, non-judgemental enthusiast, but functions as a narrative device, a figure whose curiosity and straightforward questions, as well as his gradual disillusionment, are a means to channel information or interpretation to the viewer. Ultimately, this dilutes rather than heightens Dalíland; as people confide in him or explain themselves or Dalí or Gala to him, we somehow end up with less rather than more.

Dalíland (Kismet) is on national release from 13 July 2023.