- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Opera

- Custom Article Title: Otello, Hamlet, War and Peace

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Otello, Hamlet, War and Peace

- Article Subtitle: Three nights at the opera in Munich

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Many would regard Verdi’s late masterpiece, Otello, as the most successful operatic adaptation of Shakespeare. Some have also even opined that it is better than the play. There is no doubting that it is a remarkable work and a towering landmark in nineteenth-century opera. It was a remarkable alignment of fate for this reviewer to able to see the Verdi work a day before a third viewing of perhaps the most successful Shakespeare adaptation of the twenty-first century, Brett Dean’s Hamlet.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Exterior of the National Theatre, Munich, 2017 (image from Wikimedia Commons).

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Exterior of the National Theatre, Munich, 2017 (image from Wikimedia Commons).

Otello is an opera that relies heavily on the quality of the performance of the title role, regarded by many as the pinnacle of the Italian repertoire. It calls for a voice of dramatic power, with baritonal colours in the middle register, and ringing top notes that can cut through any orchestra. Otello’s entrance ‘aria’, forty seconds of visceral power, is generally enough to judge what kind of performance awaits. Yonghoon Lee will be familiar to Opera Australia audiences as Otello in Sydney, from 2022. It was a highly promising vocal performance, lacking only some finesse in the shaping and colouring of text and tonal variety – it was his début in the role. A year later, he has moved substantially along the path to true vocal excellence, and his performance was confident, commanding the stage physically and, of course, vocally. A good Iago is an essential foil for Otello, and Munich had the distinguished Canadian baritone Gerald Finley. This is not a role that one would immediately connect with Finley’s suave and stylish vocalism, but he reveals another side of his vocal armory with this finely judged characterisation. Occasionally, one misses some of the animal power and vocal menace of the best exponents of this role, but Finley was most impressive with his oleaginous destruction of Otello, seen and heard to slimy perfection in era la note, Cassio dormiva, as he seduces Otello into doubting Desdemona’s fidelity.

The third member of the principal trio, Desdemona, is American soprano Ailyn Pérez. This a beautiful shimmering and rich sound, with a wide range of colours and an innate instinct and ability to shape musical phrases. Her opening duet with Otello showed the voice at its best, with the wide range of dynamics demanded by the music. She soared over the chorus and orchestra in the big Act Two finale, with a burnished ring in the tone. Desdemona’s final scene before her murder contains some of the most ravishing music Verdi ever wrote, with a heartbreaking ‘Willow Song’ followed by ‘Ave Maria’. Pérez has an engaging stage presence and the scene was a high point of the performance.

As one would expect of this major opera house, the other roles were cast with excellent singers from the ensemble, with the ringing tenor of American Evan LeRoy Johnson as Cassio particularly fine – a big future awaits him. The production by Amélie Niermeyer is clear and precise, with excellent character direction. The sets by Christian Schmidt suggested a large, somewhat shabby military base, which provided effective playing spaces, while the contemporary costumes by Annelies Vanlaere were striking. The performance was conducted by Briton Edward Gardner, who brought out all the power and varied colours of this sumptuous and demanding score. No performance is perfect, of course, but this was as close to ideal as one might hope and expect from the Bayerische Staatsoper.

Allan Clayton in Hamlet at the 2018 Adelaide Festival (photograph by Tony Lewis).

Allan Clayton in Hamlet at the 2018 Adelaide Festival (photograph by Tony Lewis).

The next evening it was fascinating to consider how Neil Armfield’s production of Hamlet has developed in the four different venues where it has been staged. Designed initially for Glyndebourne – with the theatre’s unique layout and employing a variety of off-stage sites for the chorus and members of the orchestra – the sonic experience was submersive and enveloping, effectively creating the claustrophobic atmosphere of the opera. The Festival Theatre in Adelaide perhaps had less of this sonic intensity, but the larger stage added some scope to the visual aspect. The film of the Metropolitan Opera production conveyed less of the claustrophobia of the work – the Met theatre is by far the largest of the world’s major opera houses, but the sound of this Rolls Royce of an orchestra and chorus was overwhelming. Munich falls somewhere in the middle with its excellent acoustic, typical of the best of the ‘traditional’ large European opera houses.

The constant and towering presence in all these performances was British tenor Allan Clayton, who has made the title role his own. Much has been written about this performance, and it remains astounding in its range of dynamics, colours, and almost reckless physical engagement. Several singers have sung in all the performances of the Armfield production, led by American Rodney Gilfrey as Claudius. He remains a powerful vocal and physical presence, and the character has gained in nuance and complexity. The same could be said for the sympathetic Horatio of South African Jacques Imbrailo, with his beautifully smooth baritone, as well as several of the other roles.

A new Ophelia was Norwegian Caroline Wettergreen, following Barbara Hannigan, Lorina Gore, and Brenda Rae. Wettergreen negotiates Dean’s fearsome vocal acrobatics with great aplomb and brings a lithe physicality to the role. The voice is even throughout the extended range and her humanity elicits the audience’s sympathy from the start. The outstanding French mezzo Sophie Koch has distinguished predecessors such as Sarah Connolly and Cheryl Barker in the role of Gertrude. Koch brought great poignancy and depth to the role, particularly at the end of Act One, while her lament over the death of Ophelia was heartrending.

American Charles Workman is a suitably pedantic and arrogant Polonius with a strong and incisive tenor and precise diction. It was wonderful to see the great John Tomlinson back as the Ghost, First Player, and Gravedigger. Acoustically, this theatre is possibly close to the ideal space in terms of size and layout to hear this opera in all its subtlety and complexity, and this is a work that has made a profound impact since its première. Vladimir Jurowski, the General Music Director in Munich, takes up the conducting duties again, having premièred the opera in Glyndebourne. As before, he is a master of this intricate and demanding score, and the orchestral playing was superb.

Again war, again suffering, necessary to nobody, utterly uncalled for: again fraud, again the stupefaction and brutalization of man. (Lev Tolstoy, 1904)

These lines are displayed at the beginning of a much anticipated performance of Sergei Prokofiev’s sprawling opera, War and Peace (1946), and are central to the overall concept and effect of this production. It demonstrates that opera, supposedly in its death throes, can be vividly relevant to the current political and cultural situation. Performing any Russian music, especially in Europe at the moment, is problematic to say the least, so this particular work, with its difficult subject matter, raised eyebrows when it was announced that the production would go ahead earlier this year. The Munich Opera obviously anticipated many possible issues arising from the first ever performance of this opera in the theatre, and a number of press announcements and various online publications addressed the event.

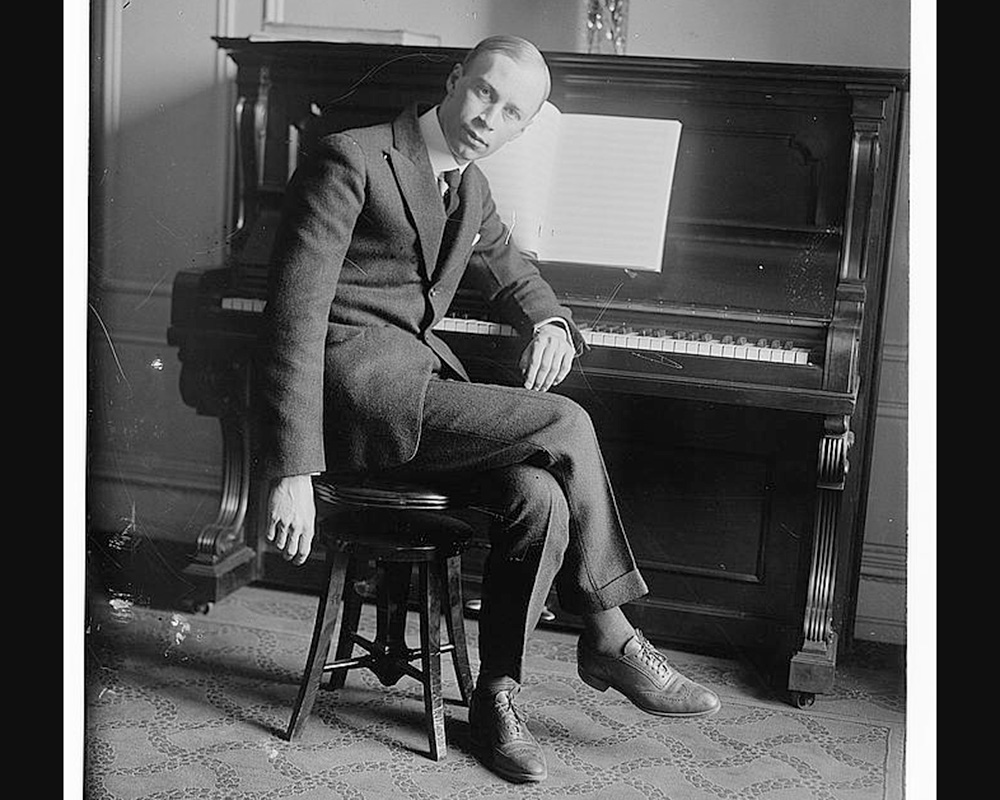

Sergei Prokofiev in 1918 (photograph from US Library of Congress George Grantham Bain Collection, via Wikimedia).

Sergei Prokofiev in 1918 (photograph from US Library of Congress George Grantham Bain Collection, via Wikimedia).

War and Peace premièred in Munich on 5 March 2023, a portentous date: the seventieth anniversary of the death of both Prokofiev and Stalin. At the time of the live television broadcast, a discussion was aired which included the conductor Vladimir Jurowsky and the director Dimitry Tcherniakov – both Russian but living in Germany, and both important and influential figures in the opera world. Of course, this dilemma is not unique to Munich, and there has been world-wide agonising concerning the performance of Russian music, and engagement with Russian art in general.

If there is an overall consensus, it is the sensible and pragmatic approach that views the current Russian regime as not representative of Russian art. Consequently, most performances have gone ahead and few Russian artists have been ‘cancelled’. In the case of an opera such as this, plans are usually made several years in advance, long before Russia invaded Ukraine. Certainly, a frisson passes through the theatre when Marshall Kutusov in the opera sings the words in his great soliloquy, ‘We will return the peace to the land of our fathers, and bring peace to other nations’, words laden with contemporary deeply ironic overtones.

The opera, just under four hours in duration, is an expert distillation of Tolstoy’s novel by Prokofiev and his wife, Mira, in which the thirteen scenes initially centre on the love story between Natasha Rostova and Andrei Bolkonsky, later contrasted with scenes depicting aspects of Napoleon’s ultimately doomed invasion of Russia, culminating in the battle of Borodino in 1812. The arrogance and foolishness of much of the Russian nobility influenced the relationship at the centre of the story; Natasha and Andrei are surrounded by a richly drawn tapestry of the mostly flawed but fascinating characters swirling around them, blending the personal with the political and historical.

So how do you stage War and Peace with the present conflict on everyone’s mind? In this production, most indications as to specific time and place are elided, so that the action takes place in an undefined country. The characters in the initial scenes appear as listless refugees, wearing a variety of contemporary winter clothes, once elegant but now somewhat shabby, carrying backpacks and dossing down in a bare, formerly sumptuous large hall. The stage set is a model of the Column Hall of the House of Trade Unions in Moscow, remembered as the setting for the funerals of Lenin and Stalin, whose bodies were on display, but also for many Communist Party congresses and other major events. In this production, this space is turned into a theatre. In effect, the ‘peace’ part of the opera emerges out of a continuing ‘war’.

The figures in the stage action evoke the countless European refugee scenes that have flashed across our television screens in recent times. We see these characters using what few materials they have at their disposal to act out the aristocratic scenes in the novel: the Tolstoy characters are played by various refugees. It is a highly ingenious conceit as it adds another layer to the artifice that is opera. The emotions appear as genuine, as if it were acted in costume in the original period of the novel, but it also provides a certain distancing of the action and offers a viable way of performing this currently almost unperformable opera. Several of the characters are costumed and made up in a way that reflects their ‘original’ Tolstoyan counterparts – a plumpish, bespectacled and sympathetic Pierre Bezukov could have stepped out of any of the many productions of the opera, not to mention film and television adaptations – but the characterisation never oversteps the overall refugee aesthetic of the production.

Sleeping bags and grubby mattresses are moved to make space for the elegant ball scenes which become a children’s party with fake tiaras, fans, jewels, and disguises. The czar appears in a Boris Godonov costume decked out with Santa Claus accoutrement. The evocative waltz melody heard at the beginning of the opera – and which will recur at the end, with emotionally devastating effect – provides a central leitmotif. Natasha teaches a clumsy Andrei the steps, and the play-acting continues with various characters moving in and out of the spotlight, the action watched disdainfully and often with sullen indifference by the others, all huddling for warmth and attempting to sleep in this potentially explosive environment.

The failed abduction of Natasha by Kuragin, the feckless womaniser, takes place while all are sleeping in the darkness around them. Finally, at the end of the first half, a young boy creeps forward, playing with a plastic toy gun and imitating aggressive actions that he has probably seen on television, or possibly around him, signalling that we are close to the second half of the opera – war. This is a world where everyone is looking for an elusive, perhaps impossible happiness, a society mired in misfortune.

Whereas the spectacular chandeliers in the Hall glittered brightly in the first part, now they are covered by a black cloth. The war scenes are described on a banner as a ‘Military-patriotic game, “The Battle of Borodino”’, and in the opening scene the characters paint Russian flags on their faces. Again, there is play-acting by the men involved as the rest of the figures on stage sit back and watch this increasingly threatening ‘game’; the weapons being brandished are real and the atmosphere becomes much grimmer. As the game finishes, injured people enter and the mattresses are placed back on the floor to tend to the wounded. All of these stage actions have an element of play about them, thus adding a sense of Brechtian Verfremdung.

Several of the potentially most contentiously propagandistic scenes have understandably been cut, but as this opera underwent almost constant revision while Prokofiev attempted to accommodate the swirling winds of political change under Stalin, this does not seem inappropriate, and one should perhaps not accuse the director of disrespecting the composer’s intentions, as is so prevalent in many other contemporary productions. One might see it as a ‘de-Stalinization’ of the opera. The time frame of the opera speeds up from early scenes separated by months, then weeks, then days, and finally by a few hours.

As we near the end, the meeting of Pierre and Andrei has a real sense of poignancy, both wondering whether they will ever see each other again, baritone and tenor voices beautifully matched in an expressive duet. Marshall Kutusov appears as one of the most dilapidated-looking of all the characters, deflating any militaristic pomposity. His conversation with Andrei is sincere and moving, while Napoleon is caricatured as a strutting buffoon playing his own ‘war game’. The burning of Moscow is suggested through depictions of looting, executions, and general violence and rape, where everyone seems to turn on one another.

For the final scene between Natasha and the dying Andrei, the darkened hall is virtually empty and very quiet. The return of the waltz as he dies is almost unbearably poignant as she lies down on a mattress next to him, attempting to keep him alive. The opera generally concludes in a rousing people’s chorus, but this has been substantially cut; we see the crowd slowly beginning to pack their belongings and clear the hall. As Kutusov proclaims that Russia is ‘saved’, he is accompanied by a rather derisive stage brass band. The theatre of war has been dismantled.

The opera has a huge cast of more than seventy characters, some of whom are doubled or even tripled by a single performer. The overall impression was of a uniformly strong cast, excellent principals in the major roles, and even those with only a couple of lines to sing displaying excellent vocal quality. One can only single out a few of the major characters. Natasha was sung by young Ukrainian soprano Olga Kulchynska, who has already performed in several important opera houses. The voice has a distinctive, silvery Slavic quality, with a gleaming, even sound throughout the range, all coupled with a delightful stage persona. She was matched by the Andrei of Moldavian baritone Andrei Zhilikhovsky. This is a superb, sumptuous voice, attractively dark in tonal quality, but with an even range culminating in a ringing top, and another strong stage personality. These are two young singers with enormous potential.

Count Pierre Bezukov, Armenian Arsen Soghomonyan, a baritone now turned tenor, gave a finely shaded vocal performance of this most sympathetic role. Field Marshall Kutusov was sung by Russian bass Dimitri Ulyanov. This is a stentorian sound in the tradition of great Russian bass voices, and Ulyanov created an interesting character despite the relative brevity of the role. Russian mezzo, Victoria Karkacheva, playing a suitably dissolute Countess Hélène Bezukova, revealed a rich, dark voice and attractive, if flighty stage persona, while her brother, Prince Anatole Kuragin, was Uzbekistan tenor Bekhzod Davronov. Within the relatively limited compass of his role, he displayed a fine voice with a ringing tone, and richly hued tonal variety.

Tcherniakov’s production makes the most of his own striking set. Costumes by Elena Zaytseva and lighting by Glen Filshtinsky are most evocative. The detail displayed by the many figures on stage in terms of characterisation and overall choreography suggests a long and complex rehearsal period. The audience reaction at this performance was extremely positive, with standing ovations for singers and conductor; from all accounts, the series of performances have been well received and attended, and the success owes much to this brilliant concept and production, made possible by the quality of performances of this large cast, filled with singers from virtually every central European country and beyond.

One leaves the theatre exhilarated, impressed, and deeply moved, but also disturbed. The opera’s troubled performance history mirrors the wider political issues of the time of its conception, but the war currently raging only a few hundred kilometres away suggests that society has not heeded Tolstoy’s sombre injunction. Opera at its best, as here, is far from being a ‘culinary’ art form, and has the capacity to provoke much thought and profound reflection.

Otello, Hamlet and War and Peace (Bayerische Staatsoper) continue at the National Theatre in Munich throughout July 2023. Performances attended: Otello on 30 June, Hamlet on 1 July, and War and Peace on 2 July.