- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Women philanthropists in our galleries

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Recently, it was disclosed that the National Gallery of Victoria now pays the salaries of ten per cent of its permanent staff from donations. The Art Gallery of New South Wales’s Sydney Modern Project currently derives around a third of its budget from private donors.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

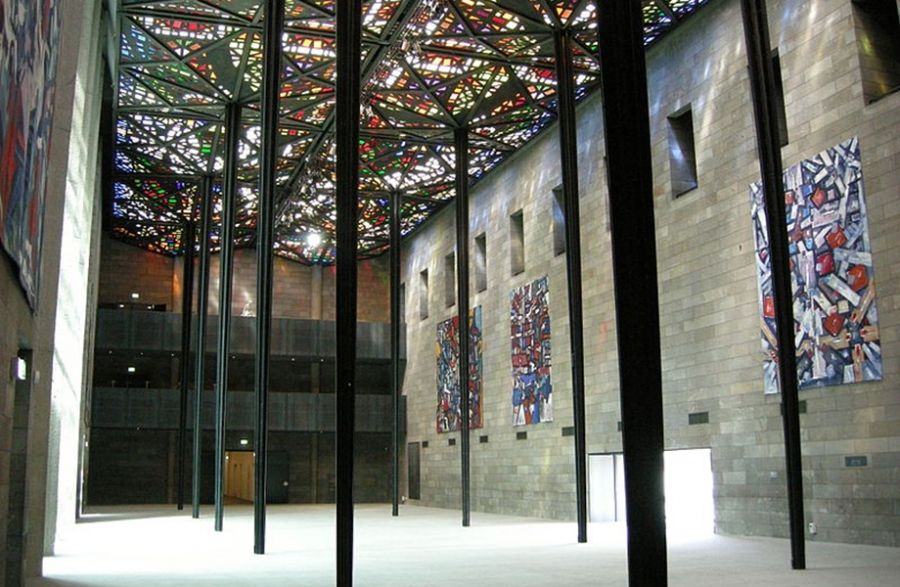

- Article Hero Image Caption: National Gallery of Victoria Great Hall (photograph courtesy of Sailko, Wikimedia Commons).

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): National Gallery of Victoria Great Hall (photograph courtesy of Sailko, Wikimedia Commons).

These women benefited from the tectonic societal shifts initiated by World War II. Women entered public life at unprecedented rates, and wealthy women stepped cautiously into the field of cultural philanthropy. An assumption about philanthropy at this time was that while men gave money and earned tax breaks, women gave time. The reality was that women did, and still do, both. Australian women gave their energy, fortunes, and collections. In the process, they helped to transform the direction of Australian art.

Women in Australia may well have taken inspiration from their sisters overseas. Internationally and historically, women had long embraced arts philanthropy as a form of soft power. Patrician women in Renaissance Europe such as Isabella d’Este and Catherine de Medici commissioned some of the finest examples of Renaissance artwork; in the 1920s, New York philanthropist Abby Aldrich Rockefeller co-founded the Museum of Modern Art. Cultural capital, social prestige, political influence: arts patronage offered all this to women who otherwise had little say in the workings of public life.

Elisabeth Murdoch, the acknowledged doyenne of Australian philanthropy, professed herself content with being a wife and mother. When her husband, Keith Murdoch, died in 1952, Murdoch inherited much of his wealth. She found that philanthropy, with its associated values of altruism and social duty, was an acceptable way for her to move outside the domestic sphere. Modest, energetic, and committed to hard work and service, she approached philanthropy as a profession. In the 1970s, she directed her energies, and fortune, to the arts. Murdoch was initially reluctant to take on a formal leadership position within the NGV: would the all-male trustees be comfortable making decisions alongside a woman? She ended up serving on the Gallery’s board of trustees for eight years, and the board of the Friends of the Gallery Library for ten.

Murdoch became a trustee of the McClelland Art Gallery on the Mornington Peninsula, a benefactor of the Art Foundation of Victoria, and funded the Timothy Potts Travelling Endowment for NGV staff. She purchased major works for the NGV, including Rembrandt’s The Women with the Arrow (1661). She helped to bring tapestry into the mainstream, founding the Victorian Tapestry Workshop in the 1980s, and commissioning a tapestry series by Roger Kemp to adorn the Great Hall of the NGV. In 1989, she was awarded the Companion of the Order of Australia in honour of her work as a Patron of the Arts.

Mab Grimwade (photograph courtesy of University of Melbourne).

Mab Grimwade (photograph courtesy of University of Melbourne).

Mab Grimwade lived in the shadow of her philanthropic husband, Russell Grimwade. The Grimwades built a diverse collection of art, furniture and Australiana that was gifted to the Ian Potter Museum of Art at the University of Melbourne as part of the Grimwade Bequests in 1973. Although Russell Grimwade is regarded as the architect of the Grimwades’ major bequests, the Miegunyah Bequests, Mab was a driving force in building and donating their collection. She wanted to leave a cultural legacy, and she did. Her archival papers are brimming with letters, receipts, and bills from Victoria’s artistic institutions, including the NGV, the Victorian Artists’ Society, and the Arts and Crafts Society of Victoria. They thank her for her generous financial gifts, invite her to gallery openings, and ask her to negotiate acquisitions. In the NGV’s permanent collection, Mab’s donations record her devotion to the Gallery: artefacts of early twentieth-century Australian and European textile design, and several works of art, one being Rembrandt’s David in Prayer (1652). In 1959, she gave £50,000 to the state government’s Cultural Centre building appeal; the NGV responded by honouring her husband in the naming of the gallery’s Russell Grimwade Gardens, making her contribution harder to discern today.

Women’s philanthropy remains an invaluable sector of the arts economy. Class is still the basis for large-scale cultural power in Australia, and most women art philanthropists continue to depend on familial and spousal wealth to facilitate their patronage. Melbourne businesswoman Naomi Milgrom, whose foundation runs the annual MPavilion and Living Cities Forum in Melbourne, and Judith Nelson, who co-founded the White Rabbit Gallery in Sydney, loom large in the contemporary art scene. In 2015, Krystyna Campbell Petty became one of the NGV’s most important donors, and her voluminous gifts of haute couture must now be valued in the many millions. The current generation’s arts patronage is informed by a manifesto of ‘socially responsible giving’ and ‘feminist philanthropy’.

Women like Elisabeth Murdoch and Mab Grimwade lived worlds apart from these current #girlboss arts patrons. For the earlier patrons, philanthropy provided opportunities for the expression of influence and social power in lives so defined by domesticity. They sat on boards, enriched permanent collections, and funded new projects. They used this power to have a say in what kind of art should be viewed publicly, which artists and art forms should be fostered, and what the future of Australian art could be. When we consider the integral role of private funding in the arts today, it is important to recognise the role of women in shaping this tradition of giving.