- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Custom Article Title: Worstward Ho

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Worstward Ho

- Article Subtitle: Late Beckett at Theatreworks

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text: It is a curious fact that perhaps the most famous lines in all of Beckett are contained in one of his least-known works, the 1983 prose piece Worstward Ho. ‘All before. Nothing else ever. Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

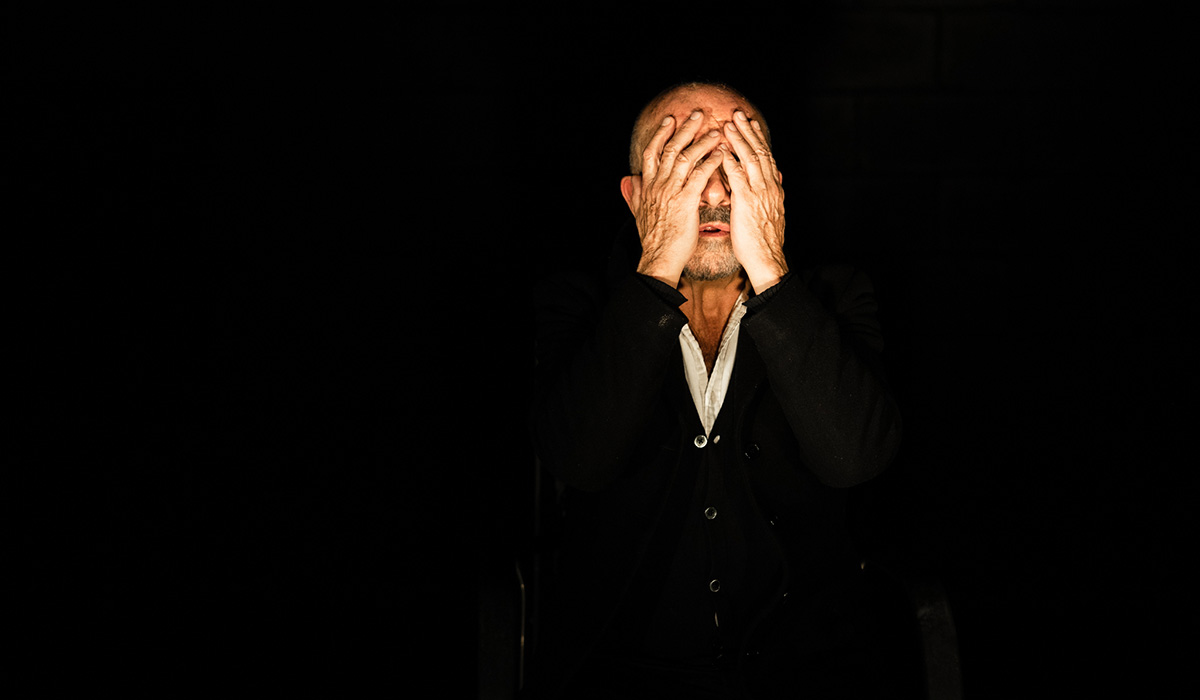

- Article Hero Image Caption: Robert Meldrum in Worstward Ho (photograph by Chelsea Neate).

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Robert Meldrum in Worstward Ho (photograph by Chelsea Neate).

- Production Company: Victorian Theatre Company

The venerable Meldrum who, with his lean, timeworn features and black overcoat, could just as easily be playing Beckett’s Krapp or Hamm, is easily the best thing about this production. If, as James Knowlson observed in his biography of Beckett, ‘the words in Worstward Ho resurrect themselves, particularly powerfully when read aloud’, then Meldrum’s performance is the proof. It is a fiendishly difficult text for an actor, brimming with neologisms and tongue-twisters (‘to last unlessenable least how loath to leasten’). For the most part, he makes it look effortless, his diction not only near faultless but also commendably varied in tone.

Robert Meldrum in Worstward Ho (photograph by Chelsea Neate).

Robert Meldrum in Worstward Ho (photograph by Chelsea Neate).

Given that Worstward Ho was not written for the stage, there are no images here as memorable as Winnie’s mound or Waiting for Godot’s leafless tree. Yet, out of the ‘dim void’, Meldrum is nevertheless able to conjure vivid pictures: an old man walking together with a child; the ‘clenched staring eyes’ of a disembodied head. These images, and the words that evoke them, keep circling back on themselves, subtly transforming like the variations in a piece of classical music. ‘Evermost’, ‘meremost’, ‘dimmost’. ‘Worse’, ‘worst’, ‘unworsenable’. They exhaust themselves, these ungrammatical coinages, and us with them. Whatever Meldrum’s skill, this production makes its sixty-minute duration feel much longer. Just as director Richard Murphet writes in his program note of having to decode the text’s ‘difficult wavelength’, so too does it take us a while to attune ourselves to its pared-down language and twistingly recombinational logic.

Worstward Ho is not simply a modernist exercise, the lugubrious venture of a word game obsessive. It is also, in its way, quietly moving. While far from grounded in any kind of recognisable reality, it shares with other works of Beckett – Krapp’s Last Tape (1958) and the television play Eh Joe (1965), to name two – a distinctly haunted quality. Like Krapp and Joe, the protagonist of Worstward Ho appears both physically and metaphysically trapped, a hostage to memory and regret – and, of course, a frighteningly indifferent universe. When, towards the end of Worstward Ho, Meldrum begins to speak of a woman using variations of the word ‘longing’, his voice cracking and eyes moist, the poignancy at the heart of Beckett’s coldness and ambivalence is revealed.

None of which is to say, unfortunately, that this is a wholly successful production. Knowlson may be right that the text of Worstward Ho benefits from being read aloud, but Murphet’s busy, unfocused direction does it few favours here. Rapid-fire lighting changes jar, working against the text’s sense of inertia, and Meldrum’s constant moving around of the few, disparate pieces of set – a desk and chair with a lamp, a wooden bench, and a highbacked garden chair – is distracting. Murphet’s interventions are often overly literal, such as when silhouettes are cast onto the back wall of the space while Meldrum is referring to the ‘shades’ which haunt his mind’s eye. It’s as though the director lacks faith in the ability of Worstward Ho to hold our attention – or, perhaps, in our ability to give it. Ironically, the effect was to make me feel less rather than more attentive, pulled out of the text’s otherwise potent linguistic spell. It all made me think that the enterprise might have been more effective as a radio play, stripped of this production’s redundancies.

It is pleasing that, at the same time as the Melbourne Theatre Company has rendered a new production of Happy Days, the Victorian Theatre Company has chosen to shine a spotlight on one of Beckett’s more unfamiliar works. It reminds us that, even towards the end of his life, Beckett was still questing, still exploring the limits of language and its inevitable deficiency. It’s a shame that Murphet, on this occasion, has not been equal to the task of successfully shepherding Worstward Ho from the page to the stage.

No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.

Worstward Ho (Victorian Theatre Company) continues at Theatre works until 3 June 2023. Performance attended: 25 May.