- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: LImbo

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Limbo

- Article Subtitle: Ivan Sen’s new film

- Online Only: No

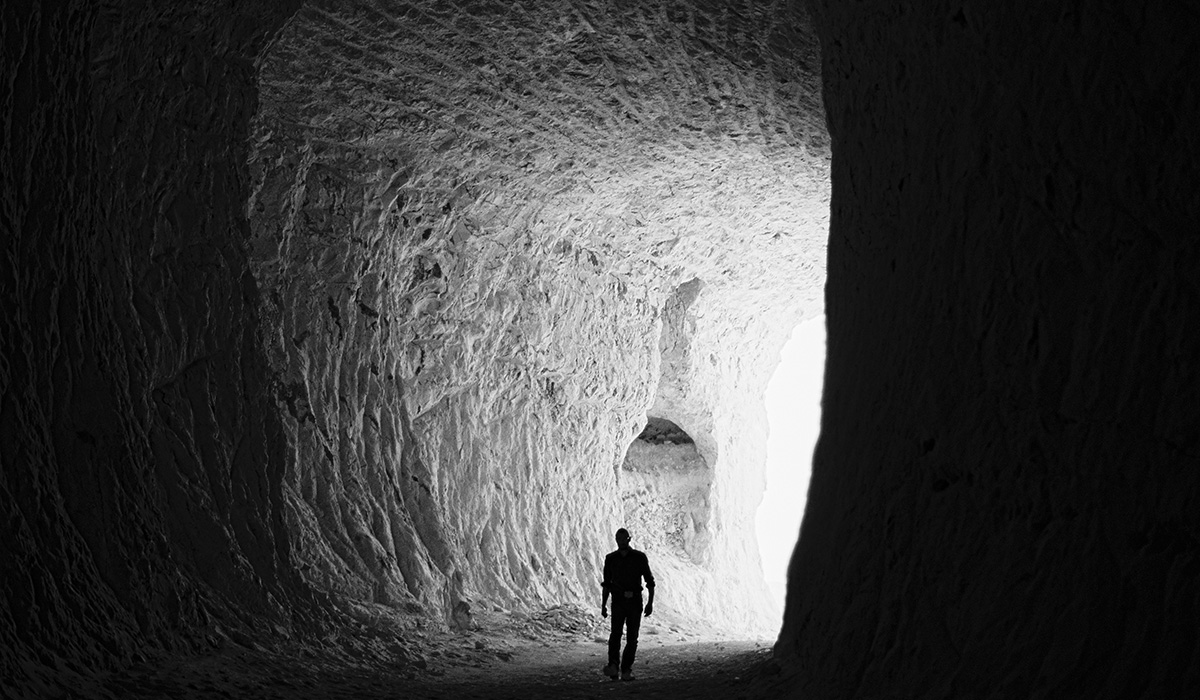

- Custom Highlight Text: At one moment in Ivan Sen’s new film Limbo (Bunya Productions), I suddenly felt as though I was watching a German Expressionist film from the 1920s, that era in silent cinema when the expressive power of the image reached its zenith, when mood emanates from every surface and character was crafted by an indivisible composite of elaborately constructed sets, sculptural lighting, texture, composition, and the gestural and postural performance of actors.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Simon Baker as Travis and Natasha Wanganeen as Emma (courtesy of Bunya Productions)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Simon Baker as Travis and Natasha Wanganeen as Emma (courtesy of Bunya Productions)

- Production Company: Bunya Productions

In Sen’s sparse soundscape, only a low muffled rumble works its way through the rock. Insulate and isolate are conjoined twins in this world of loners eking out a living underground, away from the glare of the sun, battling the odds in the search for opal. It’s a hardscrabble existence and everything in this world is hard – from the gravel-strewn land to the rusty cranes and winches looming over the skyline like giant praying mantises gulping chunks out of the land, chewing it up and spewing out the waste in mullock heaps as far as the eye can see. The monochrome cinematography leeches all the colour out of the land, as if the blood has been drained from it. This is no tourist mecca rising from the red dirt. No iridescent colours wink alluringly from seams in the rock.

Simon Baker as Travis in Limbo (courtesy of Bunya Productions).

Simon Baker as Travis in Limbo (courtesy of Bunya Productions).

The people who live here, too, are calloused by the merciless environment, both natural and social. Hurley has rolled into town to investigate a cold case: a young Indigenous girl, Charlotte, who disappeared twenty years ago, the case left unsolved by an incompetent, half-hearted police investigation. The negligence of the police in the investigation has corroded the community and torn the family apart. Drawing on experiences of his own friends and family, Sen has stated elsewhere that, for an Indigenous family, the disappearance or unsolved murder of a family member is never a cold case. The case review leads Travis to a family eviscerated by loss and grief: Charlie (Rob Collins), the girl’s brother, an opal miner who has exiled himself away from family and is wracked by loneliness and regret; and Emma (Natasha Wanganeen), the surviving sister, riven by remorse that, if she had reported what she knew back then, her sister might have been spared. Joseph (Nicholas Hope), the ageing brother of the chief suspect, who looks like the wind could blow right through him, hardly ever sees anyone and stays alone in his mine with his dog because he has nowhere else to go. This is Limbo: the edge of hell.

Sen’s earlier features – Beneath Clouds (2002), Mystery Road (2013), and Goldstone (2016) – all staged the constant police harassment of Indigenous people but, in Limbo, Sen turns an unflinching eye to the effects of that harassment: a pervasive antipathy toward the police. Travis is met repeatedly with ‘I don’t talk to white coppers’, leaving him clutching at straws. This is a world where black girls and women are targeted by predatory white men, where the police refuse to take a young Indigenous girl’s disappearance seriously, saying she’s probably just ‘gone walkabout’, where they turn the screws on the local black men and boys with violence and threats, instead of questioning the chief suspect, and where perpetrators carry on as some kind of protected species.

The detective genre gives Sen a template to explore themes he has returned to across several films, but the conventions of the genre are here pared back to bare bones, distilled to their essence. Limbo is a slow burner: there are none of the stylishly filmed action scenes of the earlier films, no supposed resolution in a final shoot-out. The focus shifts from action to the ongoing ramifications of the crime across the family and community left in its wake. The simmering tension is sustained by the taut, tightly controlled pace and the intensity of the relationships evolving between Travis and the family. Travis is jaded, but he too has a past that has left him shattered. As Charlie and Emma sense that affinity and Travis recognises his own buried feelings mirrored in the grieving family, they gradually forge relationships across the divide. The kids help to open chinks in Travis’s armour – a spark of hope and humour with their smart, cheeky forthrightness.

Simon Baker as Travis and Rob Collins as Charlie in Limbo (courtesy of Bunya Productions).

Simon Baker as Travis and Rob Collins as Charlie in Limbo (courtesy of Bunya Productions).

When we first see Travis driving into this desolate place, he is accompanied by a voice on the car radio, an evangelist spruiking positive thinking and biblically inspired hope, but it’s a stop-start message, constantly broken mid-sentence every time he turns the engine off. The stylised, staccato rhythm acts as a jarring punctuation, prefiguring the discord in the town. This religious voice weaves back into the film when Travis follows a shifty character into a church where the recorded greeting spells out what Christianity promises the damned: limbo, the edge of hell, where the ones who couldn’t get into paradise are stuck for a thousand years. In typical Sen style, this religious voice is ambiguous, hard to pin down. Is it an ironic commentary, a ventriloquist for Travis’s search for meaning and perhaps redemption, or a cynical jibe at the message of the missions, or all of the above in shifting permutations?

Other layers weave in and out of the film in complex relationships of harmony, resonance, and disjunction. Sen is both composer and conductor orchestrating this rich, complex symphony but, in a virtuoso performance, he is also the soloist on almost every instrument. His credits include writer, director, producer, director of photography, editor, composer, and visual effects supervisor. This level of creative control allows him to envisage every element of the film in an intricately crafted dialogue between each instrument. There is a unity of concept here: the layers often echo and bleed into each other: the barren landscape, austere cinematography and spare soundscape echo and reinforce the gruff, taciturn characters and the backstory shadowing every abrasive interaction.

All of the performances in the film are strong, and the casting is spot-on, from the leads down to the smallest bit-parts, which include Joshua Warrior (better known as a comedian) as wary local man Oscar, and Mark Coe, a schoolkid from Coober Pedy, as Charlie’s estranged son, Zac. Sen has a history of coaching great performances from young, non-professional actors, and the kids – Coe, Alexis Lennon as Jessie, and Tiana Hartwig as Ava – are impressive.

In the closing shot, as Travis heads out of town back across the desert, the drone camera tracks across the bleached-out, denuded minefield, up high across the perforated land, the guts ripped out of it by the mine shafts – the magnificence, the destruction, the epic scale, the beauty and the tragedy of this place, all in a single shot. The widescreen cinematography glides over this spectacular, devastated carcass as the preacher’s voice rises again on the radio, like a final testament commenting on the action.

In a mark of Sen’s flair for cinematic nuance, there is a symmetry between this final shot and the opening shot of the film. At the opening, as a young girl’s hand (Charlotte’s) paints dots on an artwork, the dots dissolve into pebbles and then into the gravelly verge. In the closing shot of the eviscerated land, it’s as if the dots that paint the story of this country have been stomped down into the ground and only the blackened scars remain. The two sequences that bookend the film – the only two in the film modulated by music – nest the narrative in a context of Country and culture bigger, more profound, than this particular story, in a condensed, experiential way that only cinema can do.

Limbo is that rare film that leaves us with lots of questions, wanting to think more about it, talk about, see it again. This accomplished film needs to be seen on the big screen to fully appreciate its power and resonance.

Limbo (Bunya Productions) opens in cinemas nationally on 18 May 2023.