- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Custom Article Title: Vale Barry Humphries

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Vale Barry Humphries

- Article Subtitle: The great comedian’s love affair with Weimar Germany

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text: Barry Humphries loved telling a story concerning a visit he and the painter David Hockney made to an art exhibition held at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1991. What drew them there was a reconstruction of the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition the Nazis had assembled in Munich in 1937 to help validate and promote their racial ideology.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Barry Humphries

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Barry Humphries

We have, of course, many reasons to celebrate the life of Humphries – actor, author, painter, and comedian. To that list we should add his love for the music and theatre of the Weimar Republic (1918–33). It, too, has been a love of some consequence.

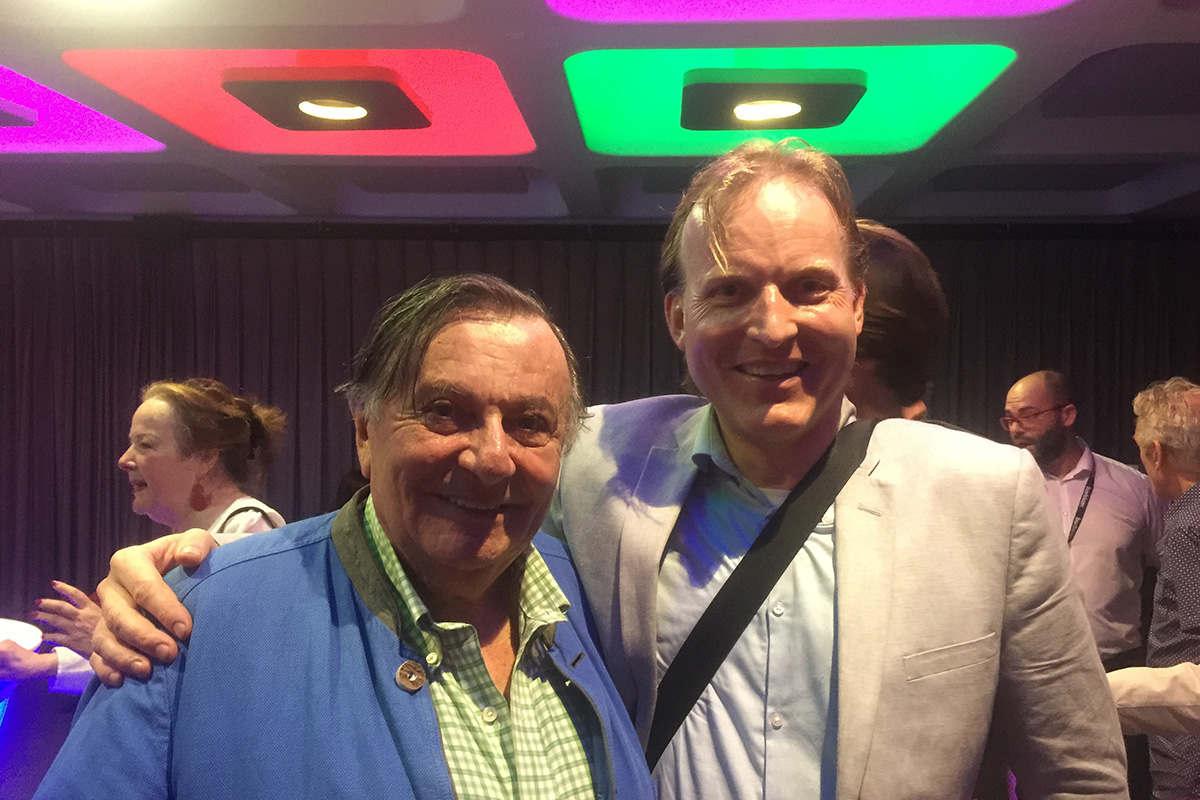

Barry Humphries and Peter Tregear in the foyer of the Barbican Centre, London, after the London premiere of Weimar Cabaret, July 2018 (courtesy of Peter Tregear).

Barry Humphries and Peter Tregear in the foyer of the Barbican Centre, London, after the London premiere of Weimar Cabaret, July 2018 (courtesy of Peter Tregear).

Some forty years earlier, Humphries had stumbled across a copy of Nicolas Slonimsky’s Music Since 1900 (1937) in his high school library. Within its pages, a kind of annotated chronology, he read tantalising descriptions of operatic rarities such as Ernst Krenek’s Jonny spielt auf (1926), Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s Dreigroschenoper (1928), and Max Brand’s Maschinist Hopkins (1929), and of the impact they had on their native audiences. He was hooked. Soon he was ordering 78s of recordings and collecting vocal scores that had made their way to Australia in the suitcases of Jewish refugees.

Although he had been born into a comfortable middle-class family, Humphries had a preconscious sense of being an outsider. He quickly recognised how a Weimar theatrical sensibility, its heady mix of cutting-edge social critique and Dada-inspired irreverence, could be repurposed for use in (or, more accurately, against) the social and aesthetic complacencies of suburban Melbourne.

He also recognised that the cultural loss that accompanied the political and humanitarian catastrophe of the Nazi era had been profound. Very few recordings were available. Many musical scores may have survived the war, but they required significant renewed advocacy and investment in order to be experienced once again as a living heritage, and there was precious little of that to be found in the decades after World War II.

Humphries decided that he would, when his burgeoning performing career allowed, assist in redressing this lack. Although he had not studied music, he had an acute sense of musical judgement. In his autobiography, More Please, for instance, he describes his first encounter with a recording of excerpts from Jonny spielt auf as ‘at once an exciting and disappointing experience’. He noted that the score sounded rather like something by ‘a pupil of Mahler played by Paul Whiteman’. ‘But’, he continued, ‘the curdled harmonies, the curious dragging rhythms and the air of melancholy that lay behind even the more sprightly episodes captivated me.’

Humphries would eventually convince the management of the forerunner to Opera Australia to consider letting him direct what would have been the Australian première of Jonny spielt auf at the Sydney Opera House. He even travelled to Palm Springs to discuss the work with its composer. Alas, the company’s management lost their nerve and decided to remount The Pirates of Penzance instead.

Humphries had more success later, when living in London. He noticed that a few doors down from his dentist’s surgery there was a doorbell with the label ‘Spoliansky’. Being aware that a Mischa Spoliansky had written numerous cabaret and film scores in Weimar Germany, Humphries knocked on the door and discovered that the composer was indeed living there, though largely forgotten. The two struck up a friendship that lasted until Spoliansky’s death in 1985.

By the time I first met him in 2000, Humphries had developed an encyclopedic knowledge of the music and musicians of this era. Through his direct support, and that of the Jewish Music Institute in London, the following year I was able to mount the UK première of Maschinist Hopkins. The speech he gave on stage before the performance served as a powerful statement of advocacy not just for this and other forgotten musical works, but also for the lives of the forgotten musicians who had created many like it.

In more recent years, Humphries would also develop significant stage partnerships (and close friendships) with Melissa Madden Gray (Meow Meow), and Richard Tognetti and Satu Vänskä from the Australian Chamber Orchestra. All four collaborated on a concert of Weimar-era music they called ‘Weimar Cabaret’, which toured the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia to great success.

I was fortunate enough to see Humphries about two weeks before his death on 22 April. I suspect he knew he was fading, yet he was keen to tell me about his latest musical discovery, Emil František Burian (1904–1959), and also to discuss how we might one day get a production of Erwin Schulhoff’s Flammen (1929) up in Australia. This enthusiasm was typical of all our encounters. His love for this repertoire was indeed profound and abiding. Long may it continue to resonate in us.