- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: Beau is Afraid

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Beau is Afraid

- Article Subtitle: A horror-comedy of tired ruminations

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text: When you wake up from a nightmare, it can feel so vivid, so real – so relevant. But over the following minutes and hours, your brain undertakes the important task of synthesising what your subconscious has subjected you to; it interprets symbols, recognises familiar anxieties, and likely suggests that you refrain from boring everyone you encounter that day with a blow-by-blow account of it all.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Beau is Afraid (courtesy of Roadshow)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Beau is Afraid (courtesy of Roadshow)

- Production Company: Roadshow

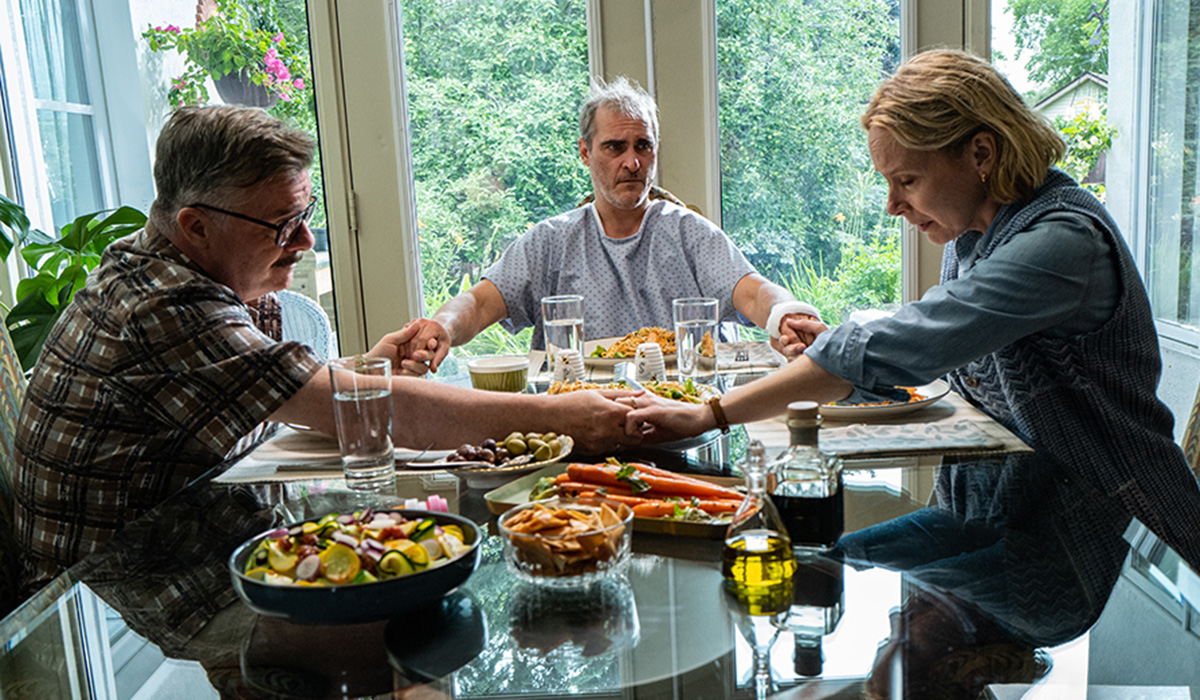

The A24 horror ingenue has followed up his massively successful Hereditary (2018) and Midsommar (2019) with this two-hour-and-fifty-nine-minute opus of anxiety. Joaquin Phoenix plays Beau, a useless middle-aged loner (putting it kindly), who is preparing to visit his mother, Mona (Zoe Lister-Jones, then Patti LuPone), a figure who looms large in the film even from its opening sequence, in which the audience, trapped inside the protagonist’s POV, is shucked from her womb. On the day of Beau’s trip, he is faced with a series of fantastical, ever-mounting obstacles: the city streets around him are a cesspool of depravity and open violence; there is a lethally poisonous spider on the loose in his apartment building; his credit card has been cancelled; his keys and luggage have been stolen. A phone call to Mona to break the news that he won’t be coming tells us everything we need to know about their relationship: with a well-timed pause or a trick of intonation, Beau’s mother can leave her son twisted with guilt. The next day, he embarks on a winding, surreal (and did I mention three-hour-long?) journey to return home to her.

Joaquin Phoenix as Beau in Beau is Afraid (courtesy of Roadshow)

Joaquin Phoenix as Beau in Beau is Afraid (courtesy of Roadshow)

Aster’s third feature may be formally classified as horror-comedy, but it’s this attempted blend of genres that proves to be Beau’s greatest weakness. Such a significant runtime might suggest the whole endeavour is designed to be one huge ‘persistence gag’ – a type of durational joke that somehow becomes funnier the longer it drags on (and just when you think it’s over … it’s not). Except Aster treats the film’s lengthy stretches of quasi-humour as horror beats instead (even musically scoring them as such) and while the timing of a punchline and the timing of a good jump scare have plenty in common, they are not automatically interchangeable, and reaching for one when the audience expects the other is not as instantly subversive as Aster might have hoped. Instead, the two modes consistently cancel each other out. Slapstick is another example; a precisely timed injury of minimal consequence can be very, very funny. Flub the timing, or turn the injury into a gruesome mutilation, and you haven’t reinvented slapstick – you’ve simply shot and missed.

Yet another example is the dialogue, which at its most fatuous recalls the stilted deadpan of Wes Anderson characters. In an Anderson film however, the players use this measured delivery to talk around things. They’re restrained by social constructs or an inability to express the depth of their feelings, hence the affectation. In Beau Is Afraid, there is little such subtext, and not a single genuine character connection cuts through its unfocused, excess absurdity. Joaquin Phoenix is, as ever, up for the challenge of his role, and he doesn’t waver even for a second in his portrayal of this detestably weak and put-upon man. Committed as he is, his performance builds to nothing – Beau spends the film in a state of constant, horrified, one-note reaction. This may be fittingly illustrative for such a profoundly passive protagonist, but it is one of many points the film successfully makes in its first thirty minutes, then insists on making again, and again, and again.

In the opening stretches of Beau Is Afraid, we watch like armchair psychologists playing bingo with the DSM-5 as we try to pin down the precise cause of our lead character’s suffering. For a while, the film plays like Neurosis: The movie, and could still go on to become many things: a portrait of agoraphobia; a pandemic-era freakout about the dangers of the outside world; a satire on modern America’s prescription pill dependency; an elegy for losing one’s parents and becoming an orphan as an adult. But as the film looks further inward, it becomes less about one man’s universal fears and more of an Oedipal odyssey into one man’s specific psychosexual failings. After that, no amount of eye-watering violence, surgical jump cuts, or villainous monologues can distract from its tired ruminations: sex equals death, woman equals Mother, Mother equals monster. In case we hadn’t been paying attention for the previous one-hundred-and-seventy minutes, Beau Is Afraid culminates with perhaps the most elaborate and expensive castration complex metaphor ever committed to screen.

So why does something like David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive work, and this does not? Both movies are rooted in and progress with the inevitable pull of dream logic. Both obsess over sex and co-dependency. It could be the fact that Lynch’s film, while frequently funny, never tries to make us laugh. Or it could be that every one of his characters, regardless of their gender, is elevated to an archetype rather than boiled down to a cruel punchline. The nightmare worlds of Lynch’s films feel like they could belong to any one of us – Ari Aster’s Beau Is Afraid feels pointedly, exhaustingly, inaccessibly his.

Beau Is Afraid (Roadshow), 179 minutes, in cinemas from 20 April 2023.