- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: Mandy Martin – A Persistent Vision

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Mandy Martin – A Persistent Vision

- Article Subtitle: A major retrospective at Geelong Gallery

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text: Before environmental psychologist Glenn Albrecht gave us the language of solastalgia, Mandy Martin painted Depaysement (2003). Martin chose a different word that also explores a sort of longing for a home that was no longer there, a safe place that predated the environmental destruction that rendered home unrecognisable.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

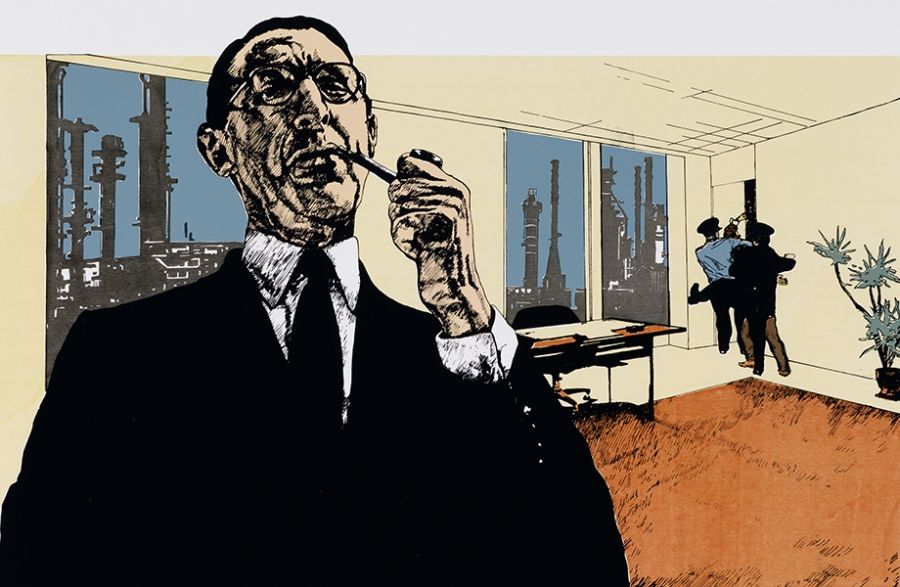

- Article Hero Image Caption: Mandy Martin, Unknown Industrial Prisoner, 1977 (photograph by Andrew Curtis)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Mandy Martin, Unknown Industrial Prisoner, 1977 (photograph by Andrew Curtis)

In the transition from her industrial and justice activism in 1970s Adelaide, to the environmental and climate activism that marked all her work from the 1990s onwards, Martin undertook her most visible major work, Red Ochre Cove, which, since 1988, has ruled over the Committee room at Australia’s new Parliament House, opened in that ‘bicentenary year’. Red Ochre Cove is twelve metres long. It is still the biggest work of public art commissioned for any building in Australia. It provides the context for every policy announcement negotiated there by the bipartisan committees of federal parliamentarians. National decisions in faraway Canberra are backed by a wonderful and deeply place-centred work of art, one that evokes Australia’s desert with its Red Ochre colours and, with the Cove, the coastal fringes where most Australians live. It is a gift from Martin’s South Australian heart, illuminated by her ecological father’s sensibilities about place.

In the time leading up to Red Ochre Cove, Australia was beginning to invest in ‘wild’ places. The campaign to save the Franklin River, the ‘last wild river’ in Tasmania, swung the federal election in 1983. Yet wilderness remained problematic and divisive. Just a decade earlier, another Tasmanian icon, Lake Pedder, had been drowned in Hydroelectric dreams.

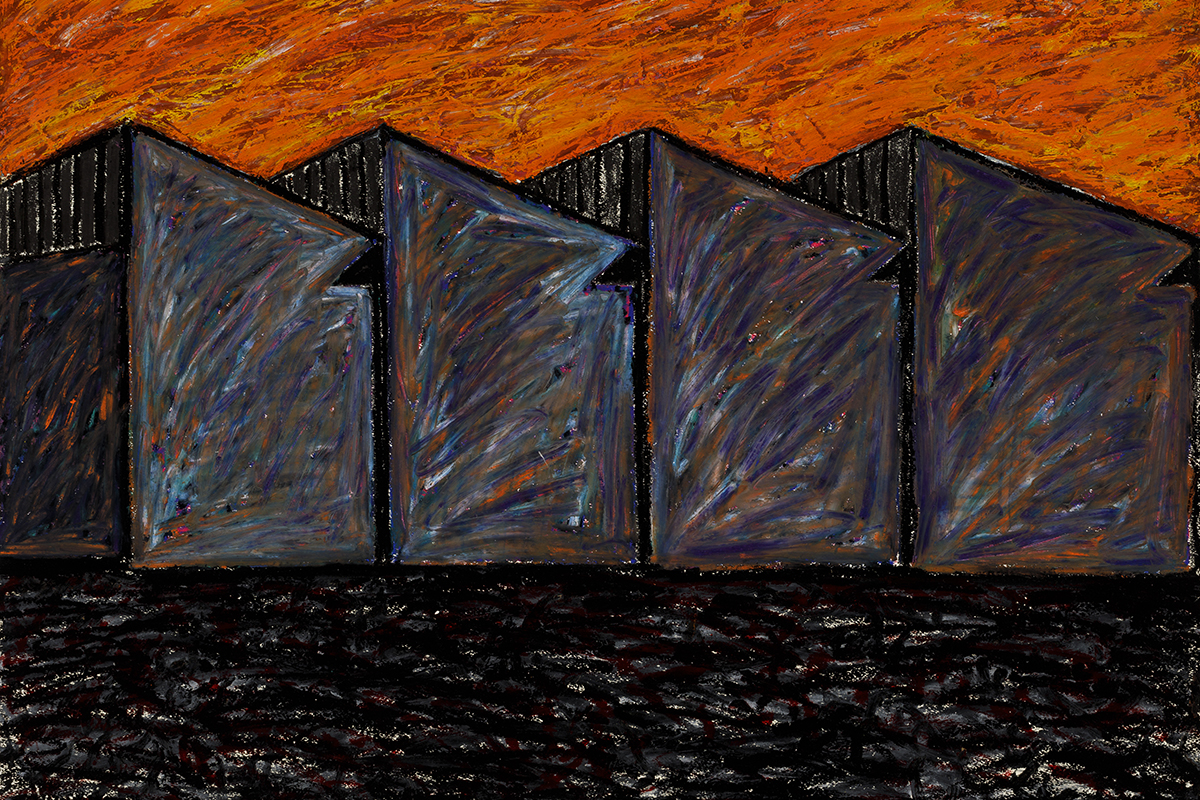

Mandy Martin, Sawtooth 1, 1981 (photograph by Andrew Curtis)

Mandy Martin, Sawtooth 1, 1981 (photograph by Andrew Curtis)

In Beyond Eden (1987), Martin painted the huge wood-chip mill looming on the edge of the emerald waters of Twofold Bay. This vast harbour, a nursery and safe haven for migrating whales, is also home to extraordinary stories of Aboriginal cultural relations with whales. Yet Eden, the biblical and faraway name of the town, celebrates the dreams of settler Australians and passing yachties. Beyond Eden explores Martin’s developing ideas inspired by philosopher Edmund Burke’s 1757 idea of the ‘Sublime’. It is a crucial work in Mandy Martin – A Persistent Vision, the important retrospective solo exhibition hosted by the industrial city of Geelong in 2022–23. Martin’s vision bridges the industrial and the ecological, the brutal aspirations of human-made architecture and the exceptional natural beauty that transcends, despite the grubby greed of exploitation and mining, in this case, old-growth forests. Jason Smith, Curator and Director of the Geelong Gallery (and a former student of Martin’s) commented that the ‘work encapsulated Martin’s abiding interests in the effects of industry at the water’s edge and in European settlement and First Nations’ ownership of country’. Like its twin work, Red Ochre Cove, Beyond Eden features a glorious parabola sky, but instead of the Cove’s optimistic upturned parabolic dish, sparkling with a shaft of sunlight, Eden’s parabola is downturned, deep in stormy clouds that echo the mood of the ‘satanic mill’ below its sky-dome.

Martin’s Sublime quest characterised the years at the turn of the millennium, in her practical environmental projects. Martin was an ‘explorer artist’, developing her work in the field with scientists, local landholders, and other scholars, creating impromptu travelling art exhibitions, drawing on the pigments and materials of the very country she depicted. The projects, in outback New South Wales and south-western Queensland, resulted in a suite of published booklets, Tracts: Back o’ Bourke (1997), Watersheds: the Paroo to the Warrego (1999), and Inflows: the Channel Country (2001).

Martin sensed the cognitive dissonance in the Australian sense of place: cultural leadership, like ecological sensibilities, still came from somewhere else. With a new Parliament House, it was time to ground national thinking here, in Australia. But which Australia? Whose Australia? The ecological power of Red Ochre Cove was clear, but how to paint in the diversity of a nation rapidly changing as the children of postwar immigrants were coming of age. The new Greek-Australians, Croatian-Australians, Vietnamese-Australians – even those born in Australia – also had ‘foreign’ ideas of home, and a double vision about home here-and-there. These were the exploited people of Martin’s 1970s industrial prints, the underpaid women feeling the oppression of big men with cigars, pipes, and American flags.

Mandy Martin, Plant 8 No. 9 Redundant, 1983 (photograph by Mandy Martin)

Mandy Martin, Plant 8 No. 9 Redundant, 1983 (photograph by Mandy Martin)

The Australian idea of Home was no longer ‘England’, as it had been when the first Parliament House was opened in Canberra in 1927. By 1988, the doctrine of terra nullius was under challenge, but Country, Indigenous Country with a capital C, had yet to find its way into the national conversation. Australia Day was 26 January, but this was a relatively recent fixture (not adopted in Victoria until 1931) and the pain raised by this date for First Nations peoples was poorly understood by non-Indigenous Australians.

By the time Martin painted Depaysement in 2003, the whiteness and foreignness of the ‘wilderness idea’ was becoming apparent. What had been described as ‘America’s best idea’ in the 1960s was decidedly out of place in twenty-first century Australia. Wilderness was something that had retreated to its origins in imaginary, biblical deserts, not the practical ecological ones that are homelands for Indigenous (and some non-Indigenous) Australians. The wilderness idea had turned inwards. It was a wrestling of the mind, not something ‘out there’, but part of the terra nullius thinking that had blinded Europeans to the ever-presence of people in this country. Depaysement is uncharacteristically blurry in style – it is an imagined landscape with formal elements of both Red Ochre Cove and Beyond Eden. The tones are similar, but the palette is softer, more aquarelle and less grit. There is no soil in the life of the mind. But there is wilderness in its abstract, distorted sky: no parabolic domes or dishes, just shards of darkness unsettling the sublime landscape. Martin’s handwritten inscription on Depayesment declares: ‘Our fear of the wilderness within ourselves matches its counterpart, the wildness without.’

The retrospective has a special capacity to consider Martin’s ‘persistent vision’ yet also to follow her commentary on Australians’ changing, awkward sense of place (and displacement) across decades. Martin’s work is alive to the trends of ecological sublime and anthropogenic destruction that mark the period leading to the emergencies of extinction, climate, and inequality that shape our world today.

Mandy Martin – A Persistent Vision continues at the Geelong Gallery until 5 February 2023.