- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Opera

- Custom Article Title: A Christmas Carol

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A Christmas Carol

- Article Subtitle: A new adaptation of Dickens's classic

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text: 1843 was quite the year in Christmas lore. It can boast both the first Christmas cards, commissioned by Sir Henry Cole, and the first edition of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. Our passion for the former may have ebbed a little in the age of digital communication, but Dickens’s novella – albeit most commonly in one of its many theatrical adaptations – continues to draw our interest. Melbourne is currently hosting the Old Vic production of Jack Thorne’s adaptation at the Comedy Theatre (with David Wenham as Scrooge). Now it also has an opera première: composer Graeme Koehne and librettist Anna Goldsworthy’s version for Victorian Opera.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Samuel Dundas as Scrooge in A Christmas Carol (photograph by Charlie Kinross)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Samuel Dundas as Scrooge in A Christmas Carol (photograph by Charlie Kinross)

Dickens was inspired to write his novella after having read a government-commissioned report on child labour in the United Kingdom. He had worked as an eleven-year-old in a factory himself, so he had a natural sympathy for the subject, as well as being a shrewd observer of the lives of the urban poor.

Melbourne may be enduring one of the coldest Decembers in living memory, but thankfully for most of us there is no proximate equivalent to the kinds of domestic squalor and miserable winter conditions in which Dickens imagined Bob Cratchit and his family to be in, nor the quintessentially nineteenth-century urban diseases that Tiny Tim was likely subject to, such as rickets or tuberculosis. Furthermore, as the evidence emerging from the Robodebt Royal Commission reminds us, Cratchit’s abusive employment conditions are much more likely to be found in the gig economy these days than in salaried employment, or where we find him in the opera -- in a generic office suite. And the reason why the Robodebt scandal did not seem to exercise us at the time (after all, we re-elected the government that conceived it) was because (as Dickens’s sought to show his readership) it didn’t involve most of us. We simply failed to care.

Other possibilities for refreshing Dickens’s social critique that were missed in this production include the transfer of a scene in a Victorian Christmas Market to, well, a Victorian Christmas market. Here was surely a chance to highlight the wasteful, vacuous consumerism that dominates our modern-day celebration. Similarly, our transformed social, (multi-)cultural, and theological relationship to Christmas was not explored. In this sense, the ghost of Christmas past cannot but haunt a modern-day adaptation, as it perhaps haunts all of us with some historical connection to the Christian tradition at this time of year.

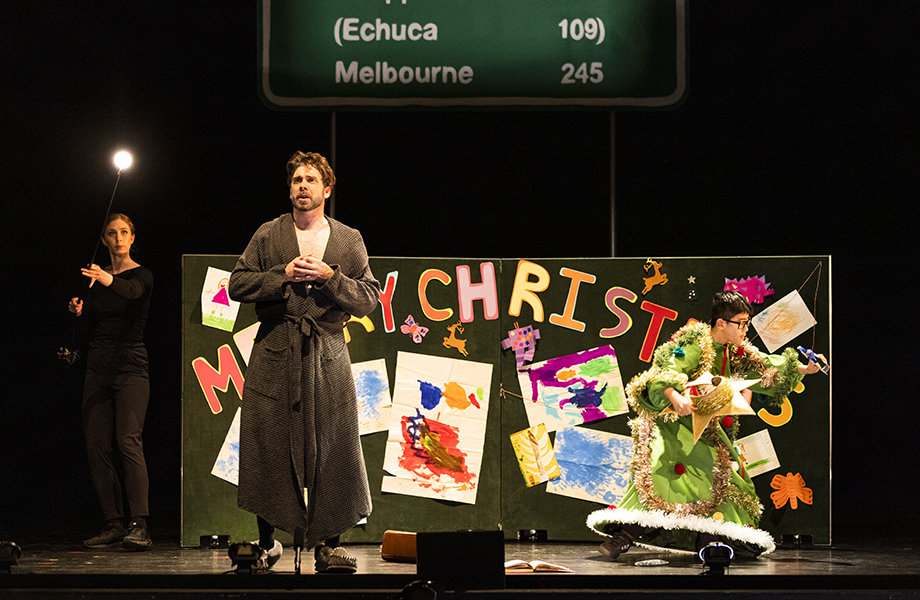

The cast of A Christmas Carol (photograph by Charlie Kinross)

The cast of A Christmas Carol (photograph by Charlie Kinross)

Goldsworthy’s libretto nevertheless does land a few goals. Koehne’s score, like many theatrical adaptations, takes a cue from the work’s title (and the fact that Dickens divides his story into five ‘staves’) to incorporate several well-known Christmas carols into the texture. Among other things, Goldsworthy takes the cue to turn ‘Once in Royal David’s City’ into a J’accuse to the audience about our treatment of the aged in nursing homes, asylum seekers, and First Nations People, in a series of cleverly rewritten verses.

For the majority of the work, however, Goldsworthy sticks to commonplace and predictable rhyming schemes, which both limits the subtlety of poetic expression and leads the score itself towards similarly repetitive phrase structures, already in abundance owing to its use of carols and other borrowings. Koehne, however, is an accomplished orchestrator and arranger, and the score rollicks along effectively, helped by some first-class playing and direction from Orchestra Victoria and conductor Phoebe Briggs, respectively.

Director Emma Muir-Smith managed the mixed cast of professional principals and amateur chorus with confidence and without fuss. The penultimate scene beside a vision of Scrooge’s grave was most effective, and the glorification of the Cratchit family Christmas pudding was a delicious coup de théâtre. Otherwise, the challenge presented by the capacious Palais Theatre, combined with Claudia Mirabello’s rather humble set, made the creation of both sufficiently grand and intimate moments on stage rather challenging. I wondered why Scrooge’s bedroom was decorated like an actual prison cell, with little other than grey blankets, instead of the metaphorical one that a modern version of Dickens’s original anti-hero would have had (indeed, we were told later that it had been filled with the latest digital consumer goods).

Samuel Dundas was Scrooge, and his attractive, rich baritone was always reliable. But he conveyed little sense of the character’s narrative arc – it seemed from the moment the ghost of his late business partner, Jacob Marley, appeared that Scrooge lost all self-confidence and conviction. We were later informed that he himself was a damaged soul from a broken family, but I suspect that Scrooge would make a more interesting and more effective medium for a broader social critique if we were made to face the possibility that the bad choices he makes were ethical and political ones, and not merely (or at least not just) an inevitable response to his own difficult backstory.

Otherwise, this was a strong ensemble performance, with all the other principals playing multiple roles. Simon Meadows (Marley/Ghost of Christmas Present), Antoinette Halloran (Ghost of Christmas Past/Freda/Woman in Bar/Thief/Tenant Woman), and James Egglestone (Bob Cratchit/Fezzoli/Belle’s Husband/Man in Bar/Pawnbroker/Tenant Man) were standouts, more than ably supported by Dominica Matthews, Askansha Hungenahally, Shakira Dugan, Stephen Marsh, Emily Burke, Michael Dimovski, and a marvellous young Maxwell Chao-Hong as Tiny Tim/Child Scrooge. Puppeteer Nadine Dimitrievitch provided the Ghost of Christmas Past with an effective spectral aspect, as well as embodying the Ghost of Christmas Future. Diction was excellent throughout, but when both the voices and orchestra are amplified (ably so by Sound Designer Jim Atkins), do we really need surtitles as well?

In the end, I was reminded that the great strength and weakness of A Christmas Carol, whether in its original form or, here, as an opera, is that it is a powerful appeal to our better selves but not a critique of the wider culture (and economic priorities within it) that encourage us to behave otherwise; it is a plea for seasonal acts of charity, but not a critique of Christianity’s limits and failures. As we know from our own era of social-media slacktivism and suspect political allegiances forged around appeals to our emotions, merely producing the right affect is not enough. It’s the effect that ultimately matters. Nevertheless, being made to feel something about the plight of those less fortunate than ourselves is at least a start.

A Christmas Carol (Victorian Opera) continues at the Palais Theatre until 17 December 2022. A livestream is available. Performance attended: 14 December.