- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: Retainers of Anarchy

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Retainers of Anarchy

- Article Subtitle: Howie Tsui’s mesmerising installation at Sydney Modern

- Online Only: No

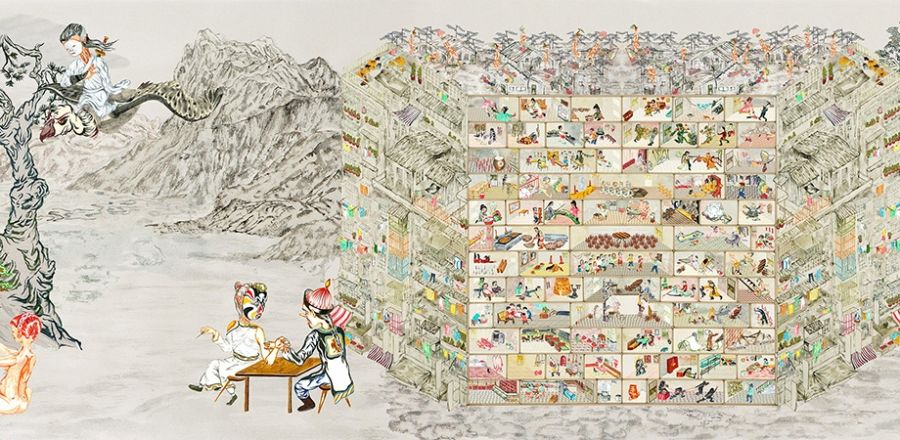

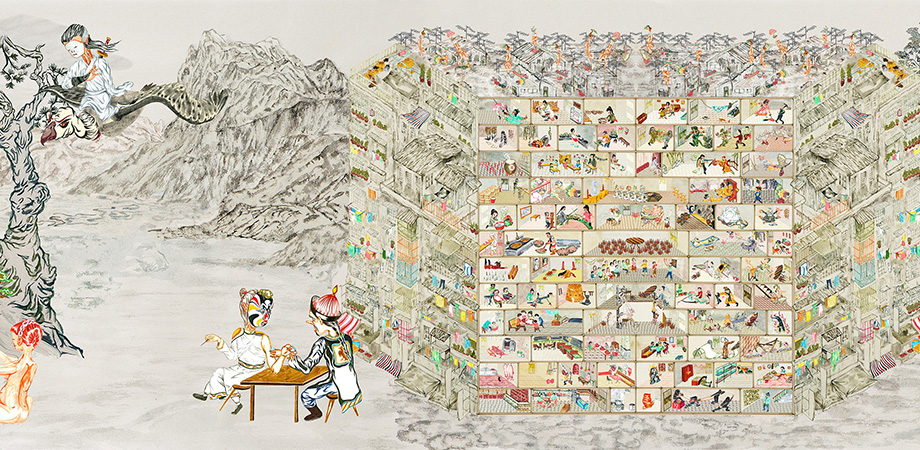

- Custom Highlight Text: Outlaw, the opening exhibition of the purpose-built new media gallery at Sydney Modern, (the Art Gallery of New South Wales’s new extension) features Howie Tsui’s mesmerising multimedia installation, Retainers of Anarchy. On a 27.4-metre long, 3.85-metre high projection, which simulates the form of a scroll painting, hundreds of images hand-drawn in ink are animated into a kaleidoscope of supernatural severed heads, grotesque tortures, and characters familiar from wuxia (martial arts) novels and television series. These fantastical images jostle with motifs of everyday life in Hong Kong and iconic figures from the pro-democracy protests that culminated in the Umbrella Movement of 2014 and were later to erupt in the all-out rebellion in 2019 and its violent suppression by Xi Jinping’s government.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Howie Tsui 'Retainers of anarchy' 2017 (video still), Art Gallery of New South Wales

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Howie Tsui 'Retainers of anarchy' 2017 (video still), Art Gallery of New South Wales

The work feels like a puzzle that we have to piece together. Hong Kong-born Tsui says that he ‘pays tribute to the current generation of Hong Kong political activists by representing them as wuxia’, legendary martial heroes of ancient China who populate the wildly popular fantasy world of martial arts fiction and film, living according to their own code, often outside the control of – or directly contesting – central government. The inhabitants of this fantasy world are combined in Tsui’s cartoon-like iconography with rebels and ghouls from the popular culture and folklore of Hong Kong and other influences from Asian popular culture – Chinese ghost stories, horror tales, Japanese manga and anime. Evoking the graphic punishments of the fourteen Buddhist hells – which include the hell of tongue ripping, boiling faeces, and trees of knives – figures everywhere are bound, hanged, decapitated, and tormented. Tsui says, ‘At heart I’m a surrealist.’

The way the drawings are animated adds to the sense of a riddle. Small scenes play out across the space of the screen, sometimes on the edge of frame, just caught in peripheral vision so that no one image has priority. Many of the figures who appear are caught in a cycle of repetitive movements, truncated like the endless looping of GIFs: a scroll painter is winched up and swung in a tree, and then again and again; a woman slurps noodles in a snippet of movement that keeps repeating around and around; a group of mahjong players morphs into swirling, twisted blobs before reconstituting and then twisting and distorting again. There is something in the perfunctory fragments of movement that confounds any attempt to take hold of them, as the interrupted images recycle back on themselves in an endless looping present with no resolution. Meaning cannot be pinned on any given sequence but is dispersed across a multitude of fragments. Clearly, these fragments fit together into some kind of story, but how they fit together is completely different to our familiar models of narrative. This non-linear storytelling is more like an assemblage: a hybrid world made of disparate fragments, each operating according to its own logic.

The world of wuxia (mou hap in Cantonese) provided a vivid fantasy world for the young Tsui growing up in the diaspora, in Nigeria and then Canada. Wuxia fiction was banned as subversive in China for much of the twentieth century, but flourished in Hong Kong where many wuxia writers wrote in exile. The most famous of them, Jin Yong (‘pronounced ‘Gum Yoong’ in Cantonese; aka Louis Cha), developed a fantasy world of highly trained martial artists who, armed with esoteric knowledge and magical powers, challenged corrupt tyrants. Tsui draws characters familiar from Jin’s serialised novels, particularly The Condor Trilogy, and there are many references to this world that will add a whole layer of pleasure and recognition for fans of the genre.

Other animated characters in Retainers of Anarchy are recognisable as icons of the Hong Kong struggle: a likeness of the young pro-democracy leader Joshua Wong is suspended in a cage, extending his tongue to eat a meal that is always just out of reach; a scholar with books on his head is dragged along the ground, arms flailing, by a cantering horse, a scene reminiscent of Hong Kong bookseller Lam Wing-kee, who disappeared in 2015, abducted and rustled away to eight months of detention in China. A young woman deploys an umbrella to fend off a barrage of flying star darts spewing from a loudspeaker. Mingling with these references, clusters of figures act out seemingly unrelated scenes across the space: a group of beggars strikes their staffs on the ground in a syncopated beat beside a man with his queue in his mouth like a gag, repeatedly lowering his neck onto the points of two raised spears; a boat bobs up and down on a stormy sea, its roof opens and it ejects a levitating abbess, who then disappears; a phalanx of hopping zombies advances in synchronised bounds, led by a Daoist master; a ghostly woman swings on a rope while a man with an eyepatch writhes against the ropes that bind him, and butterflies spiral out of an urn and buzz around him; a figure flies overhead on a giant condor, wielding a huge dagger.

Plonked in the middle of this bewildering assemblage is a massive twelve-storey tenement – the legendary Walled City of Kowloon in the centre of Hong Kong that was never under British sovereignty and that was also largely ignored by China. The walled city became a haven for refugees from China and was notorious for triads and other outcasts and criminals, but also functioned as a self-governing city free from external control. Tsui has spoken of his ‘compulsion for creating hyper-dense, maximal and layered kinetic picture spaces’. In this spirit, the front wall of the tenement is sliced off to reveal scenes playing out in each miniscule apartment in a clamour of competing animated moments: a butcher mechanically chopping meat; washing hanging on a line that suddenly turns into a screeching ghost; a noodle maker bouncing incessantly on a bamboo pole to knead dough; supernatural figures lurking everywhere; ghostly heads bobbing out of a boiling pot; a rice-cooker jiggling manically as steam rises up. On the roof of the tenement a scrabble of shaolin monks performs acrobatic feats amid a tangle of television antennae. Intermittently, a musical motif swells but then recedes, going nowhere, and the camera sweeps across the building façade, creeping closer to reveal a fitful scene, as the chatter of television screens ratchets up, and then sweeps off in another direction. This work is not simply about anarchy: anarchy is the principle that guides its construction.

Describing the source materials and iconography of Retainers of Anarchy does not begin to approach the experience of the work: a phantasmagoria that combines a rabble of fragments with a slow, meditative pace. Much of the action is set in a sparse, muted landscape that echoes the conventions of classical Chinese painting – trees, hills, a river running through – and when sequences stay on screen for long enough we have plenty of time to roam around the visual space of the screen to take in the disparate elements.

We could describe the installation as polycentric – no single image or sequence works as a unifying entity and scenes are dispersed across many ‘centres’ – but we could also describe it as polyrhythmic. The idea of polyrhythm in music is a familiar one, but a polyrhythmic image is an unfamiliar concept and much more difficult to grasp at the moment of viewing. The rhythms of Retainers of Anarchy are intriguing. Each animated motif has its own visual rhythm and no single rhythm runs through the work: a movement may last several seconds, apparently in sync with a brief musical phrase, but others last just a second or less and then repeat, over and over, producing a complex juxtaposition of rhythms. The slow, meandering flow of the landscape will suddenly switch into a riot of flickering animations. The movement of the camera adds another rhythm driven by a rationale all its own.

As an accomplished composer and sound designer, Tsui’s co-creator, Remy Siu, would be well versed in how multitrack sound recording made it possible to build much more complexity into recorded music and to create new sounds and structures. Siu builds this understanding into what he calls ‘performance apparatuses’. Retainers of Anarchy is infused with a way of conceptualising both sound and image as a multitude of ‘tracks’ or strands – stand-alone elements that can be orchestrated against each other in multiple ways. In an interview with IFF-Animation, Tsui explained how these ‘tracks’ work:

All the animations were created separately and were considered ‘assets’ … The program places the assets in this space, and then the algorithm controls the camera moves in order to frame the picture. For example, zoom out is one camera, another camera pans across slightly – there were like 40 cameras – you are programming the movement of the cameras. When you hit play, the algorithm we created dictates how the computer jumps from camera to camera. That’s how the work lived in the gallery. In this random jumping from scene to scene, zooming in and out.

The result is a new media work that layers in complexity. Encountering the work challenges us to let go of conventional expectations about storytelling and to develop new ways of engaging with audiovisual media. In an exciting evolution of this approach, Tsui and Siu have recently expanded the capabilities of the algorithm in a new work, Parallax Chambers, to allow much more control of each individual element: light, sound, camera movement and speed, and the combination of animations in a scene.

Howie Tsui (photograph by Remi Theriault, National Gallery of Canada)

Howie Tsui (photograph by Remi Theriault, National Gallery of Canada)

Tsui was initially inspired to produce Retainers of Anarchy after viewing the official contribution of China to the 2010 Shanghai World Expo: River of Wisdom, an amplified, digitally animated projection of a well-known twelfth-century Song dynasty scroll painting. The projection enlarged the classical painting from its original 5.25 by .25 metres to an epic 128 by 6.5-metre, 12-projector extravaganza. In an impressive feat of technological sophistication, an estimated one thousand figures from the static slice of life of the famous painting spring to life in a bustling, animated scene. The transformation is spectacular, and would no doubt have inspired viewers to feel wonder and national pride at the fidelity and technical genius of the animation.

Tsui’s first reaction to this spectacle was, ‘Oh wow, major spectacle, mind boggled!’ On further contemplation, however, he realised that this installation, presented as a paean to the wisdom of ancient Chinese culture, valorised an officially sanctioned vision of social harmony as the core of cultural identity and tradition over millennia. It brooked no dissent. The artwork was, he thought, using its technological prowess to project Chinese soft power both domestically and internationally. It served to manufacture consent in the maintenance of order through rigorous control, enforced by strong, centralised government.

Critics Jeesoon Hong and Matthew D. Johnson describe the gargantuan, winding screen of River of Wisdom that ‘surrounded and enfolded the spectator’. They claim that spectators were overwhelmed and potentially anaesthetised by the immersive ‘multi-sensory overload’ of the work. They say that the installation ‘intended to promote globally an image of China as a world-class techno cultural superpower … putting forward a new national brand of China as the world’s greatest past, present and future civilisation’. It was, they suggest, ‘a symbolic milestone representing the compatibility of a state-sponsored and distinctly Chinese identity with the realisation of economic prosperity’.

Enter Retainers of Anarchy, Tsui’s counter-narrative that centres figures of rebellion, in an act of ‘artistic civil disobedience’, as critic Alice Wing Mai Jim described it. Tsui wanted, he says, to turn the vision of River of Wisdom on its head, to flip it one hundred and eighty degrees, to satirise it.

Retainers of Anarchy undercuts the ethos of River of Wisdom, both politically and aesthetically. Where there was harmony and consensus, now there is mayhem and rebellion; where there was a world of seamless unity, now there is a multitude of disjointed fragments; where there was order, now there is anarchy.

When Tsui was asked by Canada’s Newest magazine to describe his current creative process and emotions as a haiku, he replied:

spongy mesophyll

filtering formaldehyde

to purge the poison

Taking up the mantle of the pro-democracy protestors in Hong Kong, who used courage, creativity, and street smarts to counter the raw power of China’s security machine, Tsui deploys the power of the imagination, the inventiveness of pop culture, and the freedom of living in the diaspora to contest this unitary, triumphalist vision of Chinese culture. In an act of cultural brinkmanship, he challenges the Chinese state to a metaphorical duel of the animated scrolls.

In the world of Hong Kong martial arts films, no one style of combat holds dominion, and the narrative of many kung fu films centres around the struggle for dominance of one school over another. In duels and tournaments, fighters seek to prove both their own mastery and the superior knowledge of their lineage. This model gives Tsui a template for a hybrid world that allows for conflict and contradiction, a clash of beliefs and allegiances, and one where real events are intertwined with the world of the imagination created through folklore and pop culture. This is a world where cultural identity encompasses both the life experience of those living on the mainland and the sensory memories and identities of members of the diaspora, and where innovation is a vehicle for the freedom to rethink the old and discover the new. It is a world that contests hegemony at its core.

Retainers of Anarchy, featured in Outlaw, continues at Sydney Modern until 2024.