- Free Article: Yes

- Contents Category: Opera

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Siegfried

- Article Subtitle: Another triumph from Melbourne Opera

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

The past few weeks in Melbourne have seen a series of extraordinary musical events that collectively represent the ultimate triumph of the creative spirit over the forces of pestilence – something that applies equally to audiences as well as performers. There is certainly, hanging in the air, a palpable spirit of communion and fulfilled expectations from our re-emergence from the stygian isolation of Covid lockdown into the iridescent aura that only live performances can achieve. In Wagnerian terms, we are all Brünnhildes, reawakening from lengthy slumber to joyfully hail the sunlight. As it was – in life and in art – at Sunday’s magnificent performance of Siegfried.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

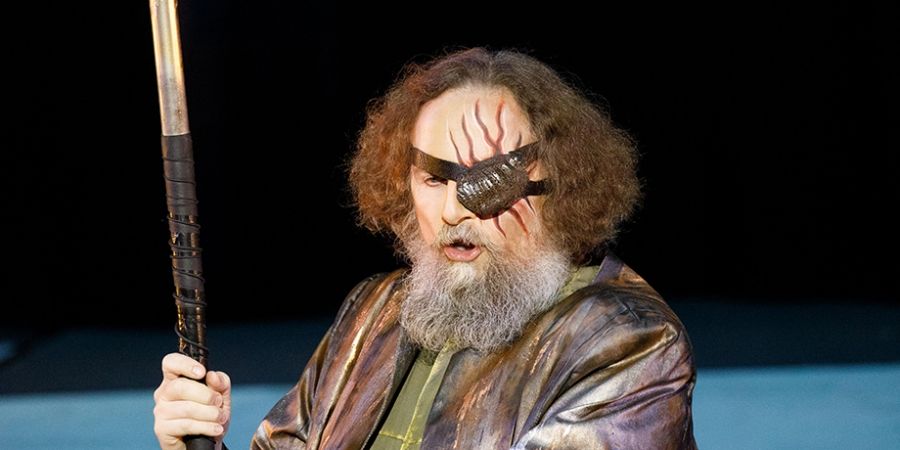

- Article Hero Image Caption: Warwick Fyfe as Wotan, from the February 2022 performance of Die Walküre

- Production Company: Melbourne Opera

Yet, Siegfried was not an isolated incident. I felt the same dizzying exhilaration at three other recent performances, all five-star quality: Victorian Opera’s recent Elektra, and the Australian World Orchestra’s Richard Strauss concert conducted by the great Zubin Mehta, both at Hamer Hall; and, at the Recital Centre, Musica Viva’s wondrous semi-staged recital of Schubert’s Winterreise, with the incomparable English tenor Allan Clayton and the fine pianist Kate Golla. Somehow, to my mind, all four events have coalesced into an overall aesthetic experience, as connected and as persuasively tensile as the invisible filaments on a spider’s web.

Siegfried is not an easy opera to bring off, either in a staged or semi-staged version. Not for nothing is the opera called the scherzo of Der Ring des Nibelungen. When you think of the distractions of the gallimaufry of sword-forging, dragon-slaying, spear-breaking, soup-making, horn call (here commanding and lyrically played by Roman Ponomariov), birdsong, and the specified (but hardly ever observed) brief appearance of a bear, there is so much going on. But Siegfried also has its magical moments of beauteous repose, such as the Forest Murmurs of Act II and the hero’s arrival at Brünnhilde’s rock in Act III – the heightened altitude conveyed so ethereally by the orchestra that one almost requires an oxygen mask.

For a couple of reasons, I did not miss a full staging at all. There will, of course, be one, next year, by Suzanne Chaundy, when Siegfried joins the other Ring operas in three cycles in Bendigo. Sunday’s version, with a slightly reduced Melbourne Opera Orchestra (concertmaster, Ben Spiers) of seventy-eight players occupying most of the platform, served to bring the musical and narrative complexities into sharper focus. This was aided by the surtitles, in German as well as English, clearly projected above the stage.

In concert, with the orchestra literally on the same level, there were times when things were too loud, and swamped the singers. This, though, was more likely down to the hall’s more intimate size and acoustic.

If Siegfried is the eponymous hero, then let it be said the orchestra was of equal heroism and stamina. It was fascinating to see them play at full tilt, and how the forces are deployed. For example, how relatively little the upper strings have to play as against how much the violas have to do. As one musical scholar put it: ‘Page after page of the score read like excerpts from some vast, dark, High Romantic Concerto Grosso for the viola section – with vocal obbligato.’

Presiding stage centre, like a benevolent penguin, was conductor Anthony Negus, whose unerring sense of structure and swift tempi allowed Richard Wagner’s score to ebb and flow almost as if on its own accord. Even moments that are often tiresome or bombastic (am I alone in thinking Mime whinges on for too long?) were fleet, yet all the more vivid. More telling was how Negus took the pace and balance of each act almost as a single paragraph. This worked especially well in Act III, which Wagner composed after a five-year absence, during which he wrote those divertimenti, Tristan and Meistersinger. This act is markedly different from the preceding two, with its almost seamless construction and more ingenious use of leitmotifs.

Anthony Negus conducting (Melbourne Opera)

The staging, though mostly restrictive, nimbly avoided being as static as a Sitzprobe, with seated, score-bound singers in front of the orchestra. Instead, there were appropriately dramatic entrances and exits, no props, such as spear or sword, and most of the artists – most notably and heroically, Bradley Daley’s Siegfried – singing from memory. All of them, even those who occasionally consulted their music-stands, really performed their roles.

‘The best part of him is the stupid boy,’ Wagner said of Siegfried. ‘The man is awful.’ The composer might have reconsidered, had he seen Daley’s thoughtful and beguiling performance. Siegfried is as notoriously difficult a role to dramatise as it is to sing: Daley achieved both with remarkable ease, combining boyish charm (his genial grin helped) with supple, never over-forced singing that ensured he lasted the distance – to that point where one great Siegfried of the past lamented, ‘In comes this bloody woman who hasn’t sung a note all night, and she sings you off the stage.’ No such fears for Daley who, by the end, still looked and sounded as if he could do it all over again.

His Brünnhilde, Lee Abrahmsen, was, in appearance and voice, a Valkyrie to the hilt, projecting her rich and gleaming voice like a silver spear right to the back of the hall. I can’t wait to hear and see what she has in store for Götterdämmerung.

Warwick Fyfe’s Wanderer-alias-Wotan was as compelling, as masterly, as he was in Melbourne Opera’s Die Walküre, in February 2022. He transformed his question-and-answer sessions with Mime into something with the intensity and ingeniousness of a chess match with only one Grand Master; and likewise in his scenes with Alberich and then Erda. Even small gestures said everything – for example, after Siegfried breaks his spear, Fyfe almost muttered his final words, ‘Go forth; I cannot prevent you’, and trudged offstage, the weight of the world on his shoulders.

Robert Macfarlane made the most of the treacherous Mime, down to some extraneous eye-rolling, tongue-sticking, hair-pulling, and assorted gestures, along with a few whines and whimpers not in the score. Simon Meadows was more restrained as Alberich, and all the more ominous because of it. Steven Gallop was a superb Fafner, essaying the dragon’s dying words with sympathy.

It takes until well over halfway through Siegfried before we hear a female voice. That it happened to belong to a Woodbird as beguiling and sweetly accurate as Rebecca Rashleigh was indeed a bonus. For a change, this Waldvogel appeared onstage to deliver her tweets, and was all the more credible for it. Deborah Humble’s beautifully sung Erda was majestic, wise, and utterly convincing.

It is tempting to regard Siegfried as strictly long haul – as one might well believe from a performance that lasted from 2 pm to just shy of 7.30. In this case, such was the high-definition quality of the playing and singing, it was but a short hop. As the final exultant notes of the love duet resounded, the audience was on its feet in a proper, instantaneous standing ovation. The performers, orchestra, and conductor looked stunned. For them, let alone us, it was all a momentous experience.

Siegfried (Melbourne Opera) was performed in concert at the Elisabeth Murdoch Hall, Melbourne Recital Centre on 25 September 2022.