Albanese’s ‘Australian Way’

Current Issue

- Events

- Book reviews

- Arts criticism

- Prizes & Fellowships

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

- Events

- Book reviews

- Arts criticism

- Prizes & Fellowships

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey

In The Möbius Book, an ingenious merging of fact and fiction by American writer Catherine Lacey, Lacey recalls including in one of her pieces of short fiction a poem about growing up with ‘an angry man in your house … and if one day you find that there is / no angry man in your house – / well, you will go find one and invite him in!’ (The poem appears in Lacey’s stinging short story ‘Cut’, first published in The New Yorker in 2019.)

Fierceland by Omar Musa

Omar Musa’s first novel, Here Come the Dogs (2014), is a rousing dramatisation of the combustible sense of displacement and dissatisfaction simmering at the underrepresented margins of Australian life. Its protagonists are singular and compelling: each is tender and violent, hopeful and despairing, pitiful and triumphant. They all possess a uniquely hybrid identity, and each is searching for something that is always out of reach.

Pissants by Brandon Jack

In The Season, Helen Garner describes a photograph of Australian Football League player Charlie Curnow celebrating a goal: ‘It’s Homeric: all the ugly brutality of a raging Achilles, but also this strange and splendid beauty.’ There is a mythic image in Australian culture of the AFL player doing battle on the football oval with the strength of Hercules or the wit of Odysseus. Brandon Jack’s Pissants, his first novel, is an inversion of this mythopoeia; it is an exposé of football culture, the false pluralism of Australian masculinity, and a deranged form of identity that runs through ‘the club’. It shows the average life of a footballer at the fringes of a team list. Jack, having played for the AFL’s Sydney Swans from 2013 to 2017, has firsthand experience of the (in)famous ‘Bloods Culture’ – one built on a mantra of self-sacrifice, discipline, and unity – and this experience shows throughout the novel.

Prove It: A scientific guide for the post-truth era by Elizabeth Finkel

Living alongside the world’s only native black swans, Australians should be more alive to the provisional nature of truth than most. For thousands of years of European history, the ‘fact’ that ‘all swans are white’ was backed up with an overwhelming data set that only the delusional – or a philosopher – would debate. But as Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume pointed out, the difficulty with inductive reasoning is that it can seem incontrovertible all the way up until it is not. But if the truth is always shifting, where do we find solid ground when our lives depend on it? And to what absolutes and experts can we refer in an era of wilful misinformation, institutional mistrust, and anti-expert populism?

A Life in Letters by Robert Chevanier and André A. Devaux, translated from French by Nicholas Elliott

In his otherwise bleak 1963 novel The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, John le Carré lets himself have a little fun with the character of Elizabeth Gold. She is an idealistic Jewish woman in her mid-twenties who works in a small library in the London neighbourhood of Bayswater. She is also a member of the British Communist Party. For Liz, however, membership is less a matter of ideology than a token of her moral commitment to peace work and the alleviation of poverty. She is disdainful of her local branch, with its petty ambitions to be ‘a decent little club, nice and revolutionary and no fuss’ – unlike her comrades in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), whose determined struggle against the militarism and decadence of the capitalist West she admires from afar.

Ripeness by Sarah Moss

Sarah Moss’s tenth novel, Ripeness, charts the burden of bearing witness to tragedies, both personal and historical. At the heart of the story are two sisters from rural Ireland: Lydia, a ballerina, and Edith, a school-leaver due to commence a degree at Oxford. When Lydia falls pregnant, the girls’s mother charges Edith with the responsibility of assisting in the birth and overseeing the transfer of the baby into the care of his adoptive mother.

Walking Sydney: Fifteen walks with a city’s writers by Belinda Castles

During the walk she takes with Michelle de Kretser along the Cooks River, the bit that snakes between Hurlstone Park and Tempe, Belinda Castles, the author of Walking Sydney, muses on the impact of Sydney’s geography. ‘On the footpath-climb to skirt the golf course,’ she writes, ‘the village-like nature of Sydney makes itself felt, the way suburbs are enclosed and cut off by ridges and valleys, cliffs and rivers, the tentacles of the harbour. A city’s form has an effect on thinking and ways of being.’

51 Alterities by Keri Glastonbury

The title of Keri Glastonbury’s latest collection of poems, 51 Alterities, evokes the title of 81 Austerities (2012) by the English poet Sam Riviere. Glastonbury’s collection is, according to its author, ‘offered as a loose “antipodean” adaptation’ of 81 Austerities, a collection that was written ‘in response to the impact of austerity measures on the arts and as a provocation on poetry as a contemporary media in the internet age’. Post-internet poetry, taking on as it does the syntax and lexis of internet discourse (especially, but not wholly, that used in social media), has become a dominant style in contemporary Anglophone poetry. When 81 Austerities was reviewed by The Daily Telegraph the headline was ‘Poetry for the Facebook Age’. Such a caption now seems laughably dated, and perhaps a little naïve, suggesting something of the dangers of writing post-internet poetry. A decade is a long time in cyberspace.

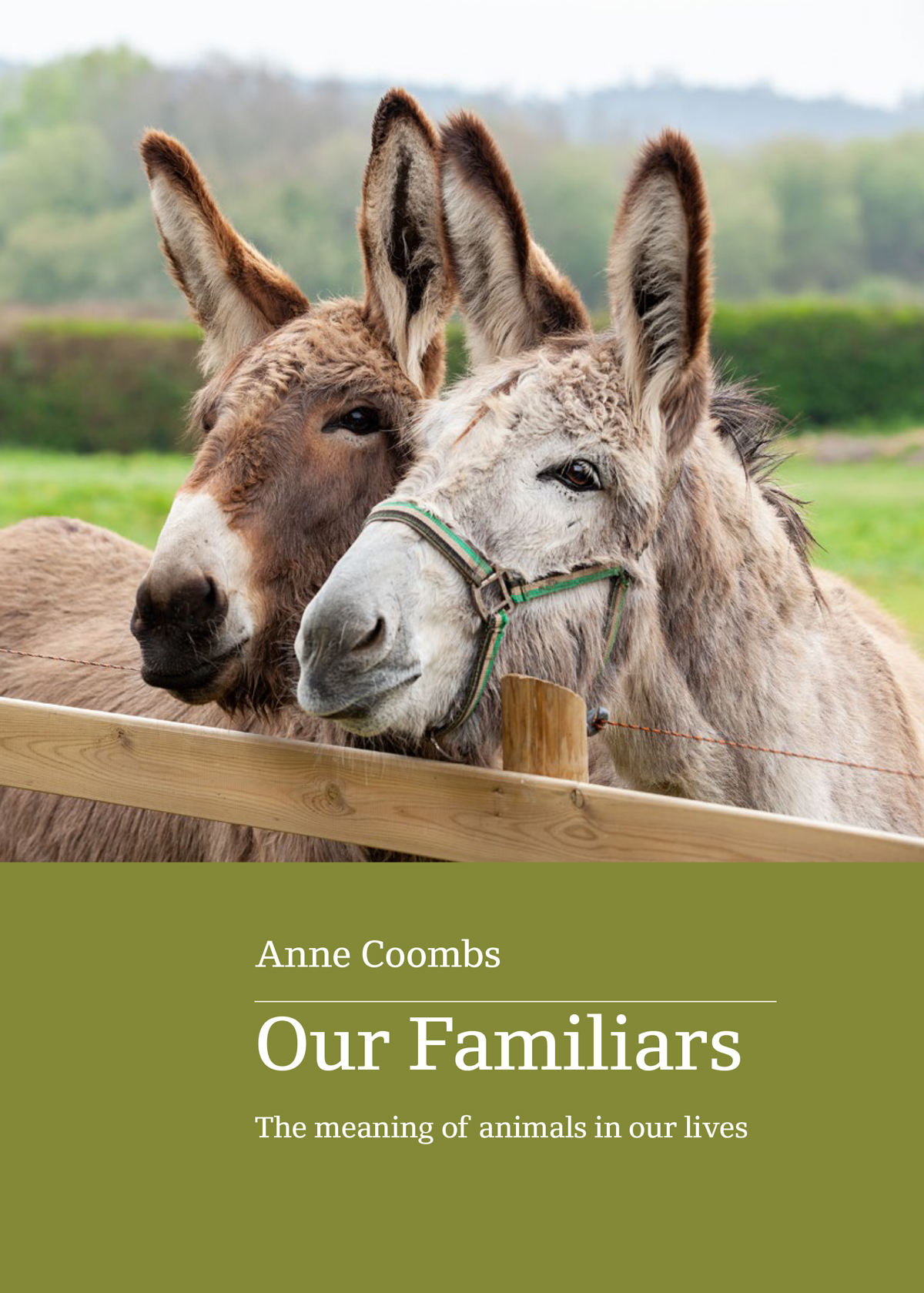

Our Familiars: The meaning of animals in our lives by Anne Coombs

The unbelievable lacework of it all – the patterns and linkages, the flickerings of knowledge and mystery, the astonishing shapes – is what Anne Coombs’s Our Familiars: The meaning of animals in our lives explores. This is a family book; specifically, a multi-species family book. Intimacies made between bodies is the soil in which the work is grown. And it comes from a writer who spent a lifetime thinking about, writing for, and working towards companionship, co-operation, and the safety of others. It is a posthumous publication too; a work fed and raised by Coombs, but finished, edited, and carried into the world by Susan Varga, Anne’s partner of thirty-three years, and close friend Joyce Morgan. Coombs died in December 2021, not long after the Black Summer fires and the Covid-19 pandemic – a time when all our interdependencies were raging (as they continue to).

ABR Arts

Bruckner and Strauss: A thoughtful performance of works by two Romantic masters

Letter from Santa Fe: 'Marriage of Figaro' and Wagner’s 'Die Walküre' at the Opera House

‘Waiting for Godot: Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter reunite for Beckett’s classic’

Book of the Week

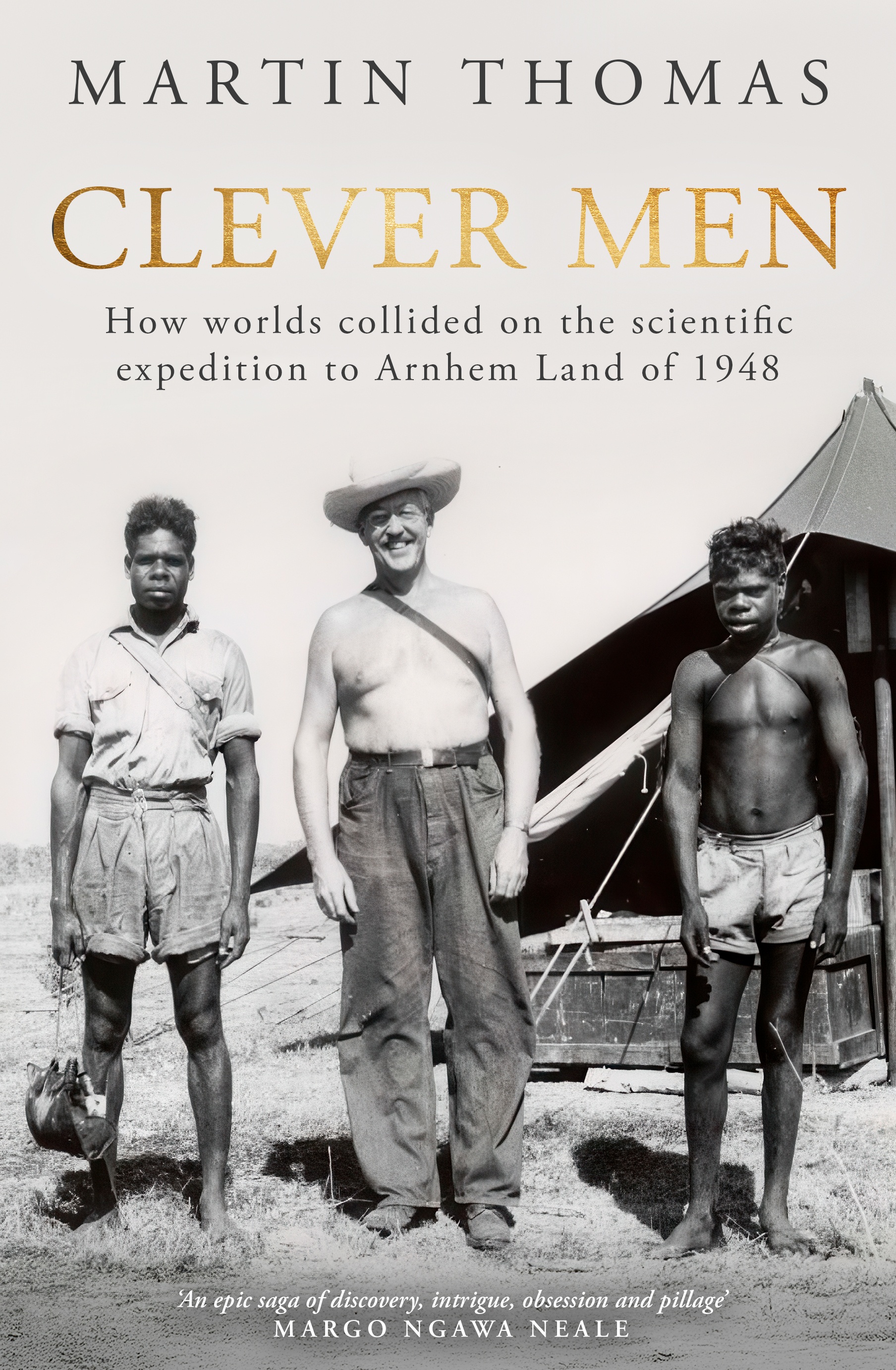

Clever Men: How worlds collided on the scientific expedition to Arnhem Land of 1948 by Martin Thomas

Soon after the conclusion of the 1948 Arnhem Land expedition, its leader, Charles Pearcy Mountford, an ethnologist and filmmaker, was celebrated by the National Geographic Society, a key sponsor of the expedition, along with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC and the Commonwealth Department of Information. In presenting Mountford with the Franklin L. Burr Prize and praising his ‘outstanding leadership’, the Society effectively honoured his success in presenting himself as the leader of a team of scientists working together in pursuit of new frontiers of knowledge. But this presentation is best read as theatre. The expedition’s scientific achievements were middling at best and, behind the scenes, the turmoil and disagreement that had characterised the expedition continued to rage.

From the Archive

Sense and Nonsense in Australian History by John Hirst

John Hirst is a throwback. I don’t mean in his political views, but in his sense of his duty as an historian. He belongs to a tradition which, in this country, goes back to the 1870s and 1880s, when the Australian colonies began to feel the influence of German ideas about the right relationship between the humanities and the state. Today it is a tradition increasingly hard to maintain. Under this rubric, both historians and public servants are meant to offer critical and constructive argument about present events and the destiny of the nation. Henry Parkes was an historian of sorts, and he was happy to spend government money on the underpinnings of historical scholarship in Australia. The Historical Records of New South Wales was one obvious result, and that effort, in itself, involved close cooperation between bureaucrats and scholars. Alfred Deakin was likewise a man of considerable scholarship (and more sophisticated than Parkes), whose reading shaped his ideas about national destiny, and who nourished a similar outlook at the bureaucratic level.