Albanese’s ‘Australian Way’

Current Issue

- Events

- Book reviews

- Arts criticism

- Prizes & Fellowships

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

- Events

- Book reviews

- Arts criticism

- Prizes & Fellowships

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey

In The Möbius Book, an ingenious merging of fact and fiction by American writer Catherine Lacey, Lacey recalls including in one of her pieces of short fiction a poem about growing up with ‘an angry man in your house … and if one day you find that there is / no angry man in your house – / well, you will go find one and invite him in!’ (The poem appears in Lacey’s stinging short story ‘Cut’, first published in The New Yorker in 2019.)

The Shortest History of Turkey by Benjamin C. Fortna

Can a ‘shortest history’ of Turkey, including the expansive history of the Ottoman Empire, work? As well as covering imperial grandeur, it must address complex and sensitive issues such as the Kurdish conflict, the Armenian genocide, Islamism, slavery, and autocracy. Benjamin C. Fortna, a Middle Eastern historian, successfully combines sympathy and interest in Turkey with a candid examination, including of darker aspects of its past.

‘Weather’

These days, evenings are heavy

with clouds that refuse to crack, to open

a window is let in the night

creatures, which flutter and tumble

into the glow of a phone

Poet of the Month with Ellen van Neerven

Ellen van Neerven is a writer and editor of Mununjali and Dutch heritage. Their books include Heat and Light (2014), Comfort Food (2016), Throat (2020), and Personal Score (2023). Ellen’s first book, Heat and Light, was the recipient of the David Unaipon Award, the Dobbie Literary Award, and the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards Indigenous Writers’ Prize. Ellen’s second book, Comfort Food, was shortlisted for the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards Kenneth Slessor Prize and highly commended in the 2016 Wesley Michel Wright Prize. They live and write on unceded Yagera and Turrbal dhagun.

On the Calculation of Volume: Book I by Solvej Balle, translated from Danish by Barbara J. Haveland & On the Calculation of Volume: Book II by Solvej Balle, translated from Danish by Barbara J. Haveland

In a famous thought experiment based on the notion of ‘eternal return’, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche asked what it would be like to live the same life over and over again, for eternity. Nietzsche’s intention was to set a kind of test that encourages us to consider whether we are living our best life, the life that makes us happiest.

Now, the People!: Revolution in the twenty-first century by Jean-Luc Mélenchon, translated from French by David Broder

Jean-Luc Mélenchon is famous in France for his booming eloquence, his rich vocabulary, and his deep knowledge of history and politics. The firebrand orator was born in 1951 in Tangier, Morocco, to parents of Spanish and Sicilian descent, then moved to France with his mother in 1962. After a degree in philosophy and languages he was a schoolteacher before becoming a political organiser and elected politician, notably from inner-city Marseille.

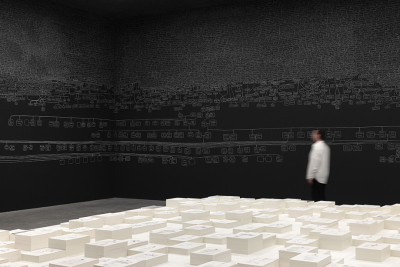

Our Story: Aboriginal Chinese people in Australia edited by Zhou Xiaoping

It is deeply sobering to be writing about the depth of the history of multicultural Australia only days after rallies against immigration have been held and in the midst of a palpable and disturbing negative response to non-white immigration. There are echoes of the shameful twentieth-century White Australia policy. Far from being a recent phenomenon, multiculturalism has been an integral aspect of Australian society since European settlement in the late eighteenth century. This collection, edited by the artist Zhou Xiaoping, is the outcome of a three-year research project and is the companion monograph for Our Story: Aboriginal Chinese people in Australia, a free, ground-breaking exhibition currently at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra that will run until late January 2026.

The Sea in the Metro by Jayne Tuttle

Jayne Tuttle’s The Sea in the Metro is the third book in a trilogy of memoirs about living, working, and becoming a mother in Paris. Like Paris or Die (2019) and My Sweet Guillotine (2022), Tuttle’s latest book applies a sharp scalpel to her own psyche while playing with genre. She explores the brutal realities of giving birth and raising a toddler in a foreign city, the seemingly impossible task of balancing motherhood with paid work, the joys and hardships of striving to be a capital ‘W’ writer while copywriting for cash, and what family might look like in brittle, Parisian culture. Tuttle also examines the complex ramifications of a near-death experience and a hospital birthing trauma on her ongoing physical and mental health – and intimate relationships.

Electric Spark: The enigma of Muriel Spark by Frances Wilson

Some literary biographies are best known for their gestation – or malgestation. Some authors, we might go further, should have a big sign around their neck – noli me tangere. Muriel Spark is one of them. Her voluminous archive, lovingly tended all her life, is full of booby traps. Twice she went into battle with biographers: first Derek Stanford, a former lover; then Martin Stannard, whose biography of Evelyn Waugh she had admired.

ABR Arts

Bruckner and Strauss: A thoughtful performance of works by two Romantic masters

Letter from Santa Fe: 'Marriage of Figaro' and Wagner’s 'Die Walküre' at the Opera House

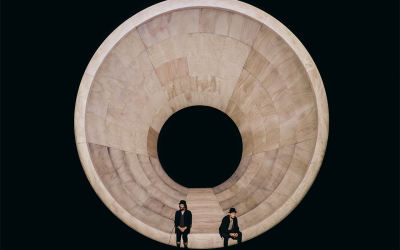

‘Waiting for Godot: Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter reunite for Beckett’s classic’

Book of the Week

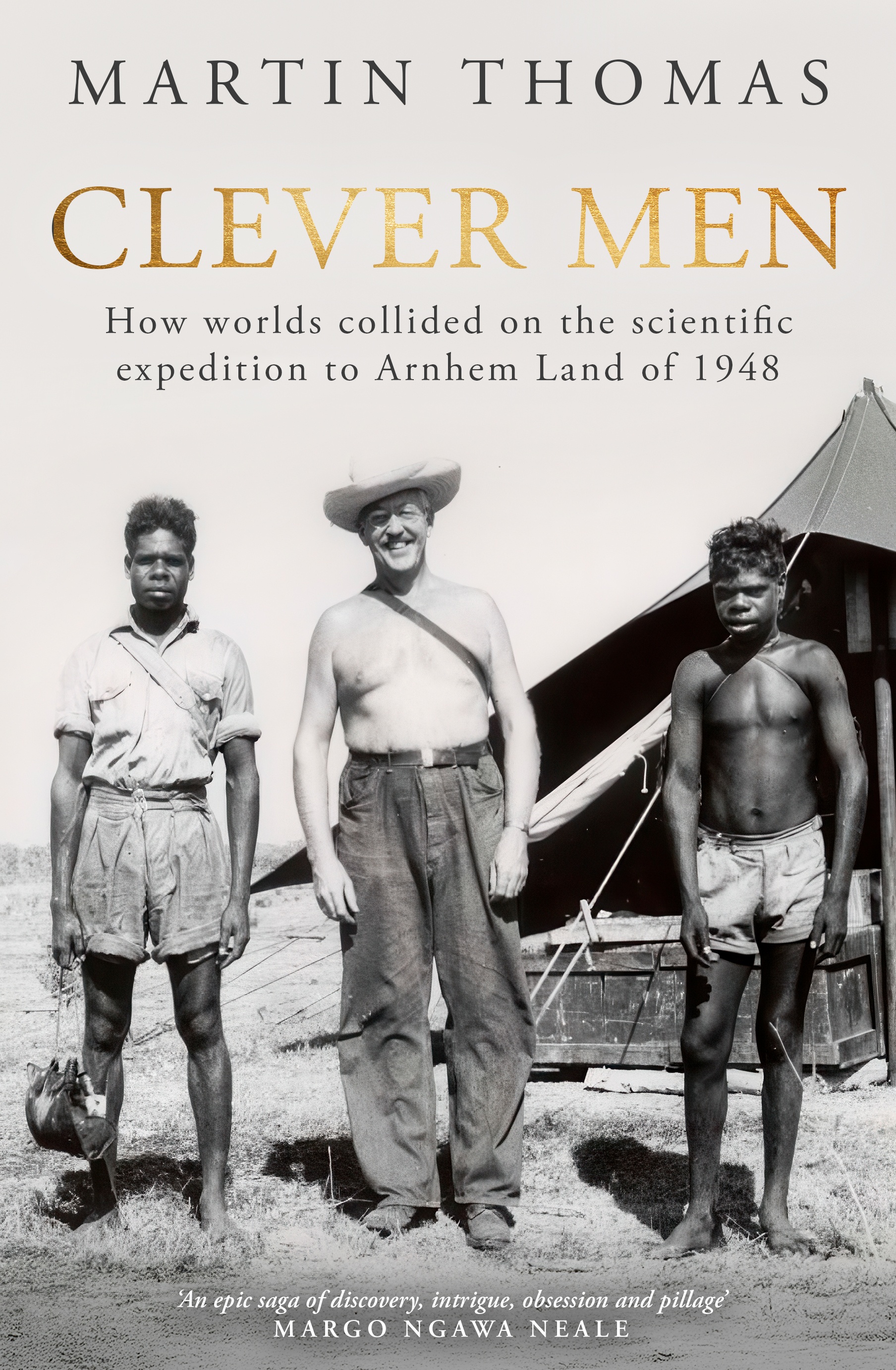

Clever Men: How worlds collided on the scientific expedition to Arnhem Land of 1948 by Martin Thomas

Soon after the conclusion of the 1948 Arnhem Land expedition, its leader, Charles Pearcy Mountford, an ethnologist and filmmaker, was celebrated by the National Geographic Society, a key sponsor of the expedition, along with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC and the Commonwealth Department of Information. In presenting Mountford with the Franklin L. Burr Prize and praising his ‘outstanding leadership’, the Society effectively honoured his success in presenting himself as the leader of a team of scientists working together in pursuit of new frontiers of knowledge. But this presentation is best read as theatre. The expedition’s scientific achievements were middling at best and, behind the scenes, the turmoil and disagreement that had characterised the expedition continued to rage.

From the Archive

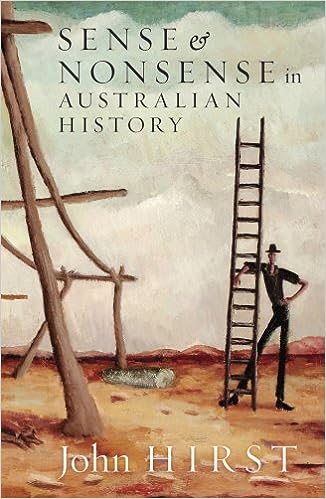

Sense and Nonsense in Australian History by John Hirst

John Hirst is a throwback. I don’t mean in his political views, but in his sense of his duty as an historian. He belongs to a tradition which, in this country, goes back to the 1870s and 1880s, when the Australian colonies began to feel the influence of German ideas about the right relationship between the humanities and the state. Today it is a tradition increasingly hard to maintain. Under this rubric, both historians and public servants are meant to offer critical and constructive argument about present events and the destiny of the nation. Henry Parkes was an historian of sorts, and he was happy to spend government money on the underpinnings of historical scholarship in Australia. The Historical Records of New South Wales was one obvious result, and that effort, in itself, involved close cooperation between bureaucrats and scholars. Alfred Deakin was likewise a man of considerable scholarship (and more sophisticated than Parkes), whose reading shaped his ideas about national destiny, and who nourished a similar outlook at the bureaucratic level.