- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Nature Writing

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bushwalks and rambles

- Article Subtitle: Examining Australian walking habits

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At what point does a ramble or meander through the bush become a bona fide bushwalk? Was my two-hour stroll near Wolli Creek during semi-lockdown – when I locked eyes with the now-maligned fruit bat – a bushwalk or just a ramble? Answers to these questions vary wildly according to the conflicting approaches to bushwalking detailed in Melissa Harper’s updated version of The Ways of the Bushwalker (2007).

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Caitlin Doyle-Markwick reviews 'The Ways of the Bushwalker: On foot in Australia' by Melissa Harper

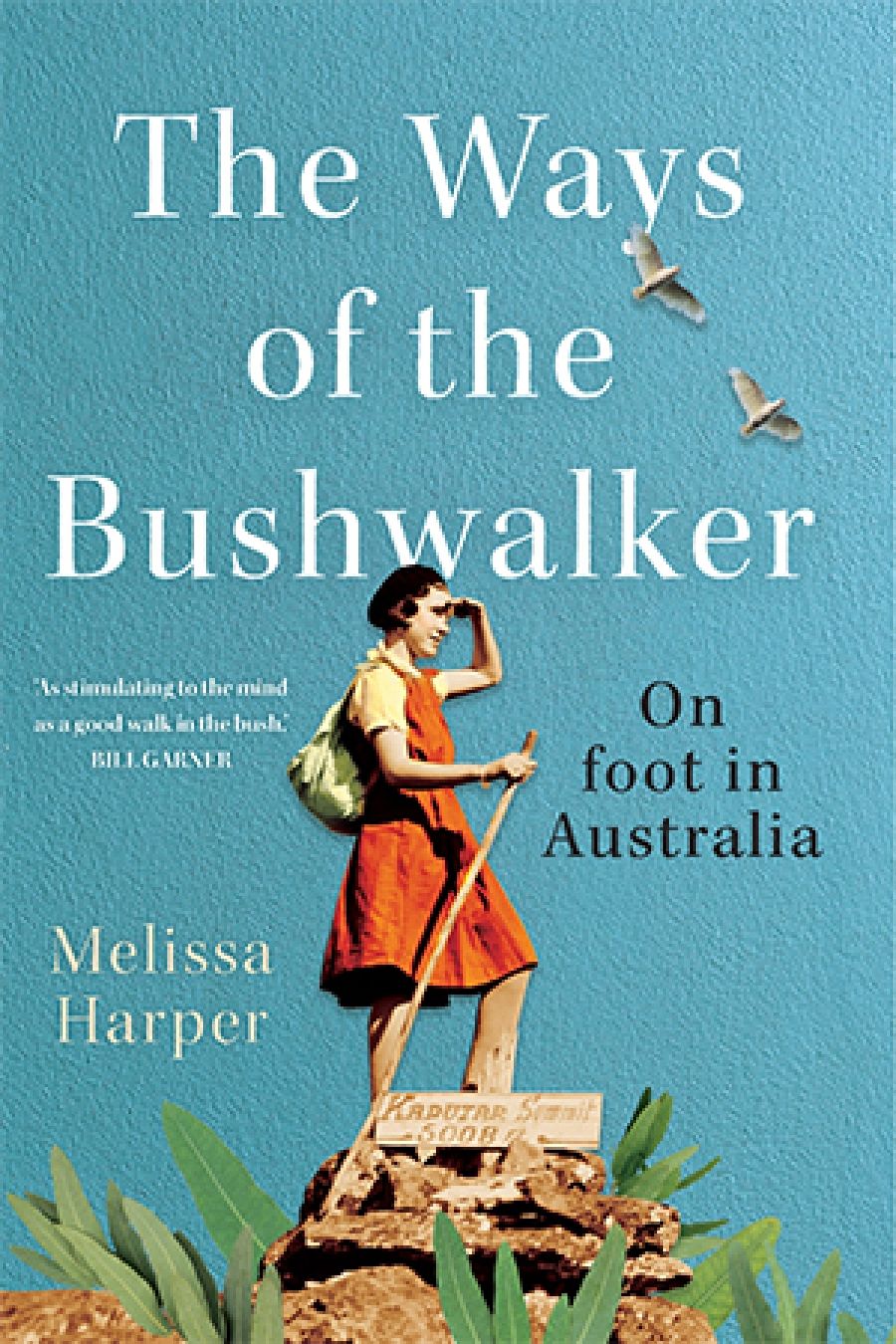

- Book 1 Title: The Ways of the Bushwalker

- Book 1 Subtitle: On foot in Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.99 pb, 381 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/n1Rrox

From early on, arguments have raged over what constitutes legitimate ‘bushwalking’, including a thread of élitism and exclusivity still present today. Influenced by the Romantic literature of the nineteenth century, with its notion of the sublime, middle-class Australian walkers often saw bushwalking as a means of cultivating one’s finer senses and intellect away from the hubbub of industrialised cities. For intellectuals like George Sutherland, founder of the Melbourne Review, bushwalks were also social occasions, an opportunity to throw off the shackles of polite society to thrash out philosophical arguments. As interest in the natural sciences grew, it became fashionable to spend long days ‘botanising’ or examining curious rock formations as they walked.

A section of upper-class bushwalkers rejected what they saw as an indulgent approach to bushwalking. These Robinson Crusoe-like adventurers valued self-sufficiency and, like the nascent Scouting movement, saw bushwalking as a means of cultivating skills needed for war. Even gentlemen bushwalkers took pride in carrying minimal supplies and subjecting themselves to Australia’s harshest landscapes.

Harper makes clear that what defined self-titled bushwalkers was their ability to opt out of these hardships, unlike the swagmen and workers who walked the country roads and bush in search of work during the depression of the 1890s. The romanticisation of the swagman figure by both bushwalkers themselves and Australian literature – from Henry Lawson to Les Murray – has arguably led to the existence of a national myth conflating the image of this intrepid adventurer with the impoverished swagman, despite the marked differences in their material circumstances. Scattered throughout some of our most prized literature is ‘a bush myth created by an alienated urban intelligentsia who then projected their values onto the outback’.

Although the Australian bush and our apparent collective connection with it loom large in the national imagination, access to the bush since colonisation has remained restricted along the lines of race and class. Harper shows how middle-class bushwalkers reacted with scorn when thousands of mostly working-class people began taking advantage of day hikes organised by the railways in the 1930s. She reveals that engagement in bushwalking as a leisure activity remains low among LOTE and First Nations communities. And while Indigenous struggles to maintain access to their traditional lands have been a feature of our history from the beginning, they rarely feature in bush poetry.

Perhaps ironically, most of the experiences of the bush described in The Ways of the Bushwalker, whether those of a wealthy explorer or a working-class day-hiker, are premised on the separation of nature and ‘real life’ in an industrial system imported from Britain, and on a profound alienation from the environment. Harper is careful to distinguish the walking habits of settlers from the practices of Aboriginal people, whose way of moving through the landscape wasn’t determined by a need to escape the grind of industrial cities but by a relationship with nature based on mutual reciprocity and inextricably bound up with their economic and spiritual lives.

In the last chapter, Harper delves into recent debates around the concept of ‘wilderness’, or pristine nature, and how we conceive of the pre-colonial landscape and the founding myth of terra nullius. She criticises the often racist and dismissive attitudes of walkers towards Indigenous people, and rejects the absurd claims of bushwalkers to be charting new, ‘undiscovered’ territory on their adventures.

Some of Harper’s cheerful descriptions of bushwalking in earlier colonial times manage to skip over the less wholesome aspects of settlers’ activities, drawing too hard a line between the innocent adventures of colonialists on their days off and the project of colonisation as a whole. Whether or not the Macquaries or Macarthurs marvelled at the beauty of the landscape they later violently expropriated seems an odd thing to focus on without mentioning the fact or nature of the expropriation. This new edition could have referenced the large post-2007 body of research detailing the Frontier Wars, which were still raging in the early 1900s. Similarly, while Harper problematises the tendency of the tourism industry to ‘monetise nature’ – as well as the conflict between equitable access and the protection of vulnerable ecosystems – discussion of the most damaging commercial practices being carried out in the same areas, such as land-clearing, is conspicuously absent. These omissions risk perpetuating some of the very myths that Harper confronts about just how healthy our relationship with nature is in Australia.

If the desire of tens of thousands of people in this country to connect with the natural world can be seized upon to protect the landscapes through which they walk, perhaps there is a chance that this relationship can be turned around.

Comments powered by CComment