- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Labour of love

- Article Subtitle: The biography of a pedagogical innovator

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

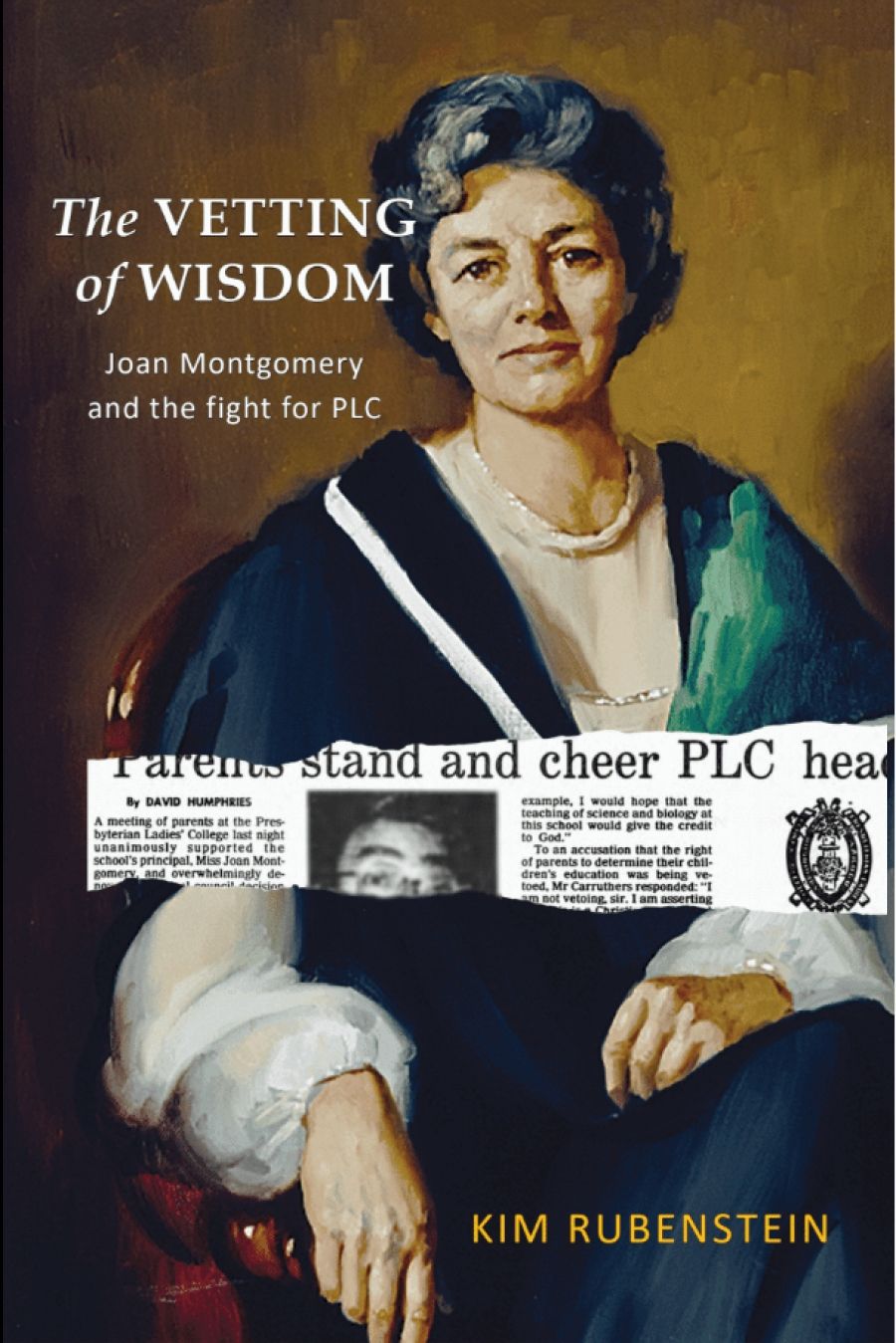

Kim Rubenstein’s biography of Joan Montgomery, the venerable former principal of Melbourne’s Presbyterian Ladies’ College (PLC), has been thirty years in the making and is the definition of a labour of love. It involves Rubenstein, a distinguished and worldly legal scholar and human rights campaigner, revisiting scenes from her own life. She was a pupil at Montgomery’s PLC. As a first-year law student, she addressed the remarkable public meeting in April 1984 that opposed Montgomery’s defenestration by Presbyterian reactionaries, who were avenging the formation of the Uniting Church seven years earlier by asserting control over the school. Rubenstein’s subsequent career has been that of a distinguished old girl following the tenets of a liberal education.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Gideon Haigh reviews 'The Vetting of Wisdom: Joan Montgomery and the fight for PLC' by Kim Rubenstein

- Book 1 Title: The Vetting of Wisdom

- Book 1 Subtitle: Joan Montgomery and the fight for PLC

- Book 1 Biblio: Franklin Street Press, $39.95 pb, 399 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/e4ryRz

Montgomery, who recently celebrated her ninety-sixth birthday, is almost as much an educational institution as PLC, where she was herself a schoolgirl. A spinster who was eighteen when her widowed father died, she has always exuded a powerful autonomy, as serene as the Dudley Drew portrait that adorns the cover of The Vetting of Wisdom. Rubenstein rather nicely parallels her with Queen Elizabeth, whose coronation Montgomery saw as a young Australian traveller; the new monarch was ‘a role model, kindred spirit and virtual mentor’. In Australia, Montgomery taught at Frensham and Tintern before taking over at PLC in January 1969 after a decade running Clyde. She also acted as president of the Association of Independent Girls’ Schools of Victoria and president of the Association of Heads of Independent Girls’ Schools of Australia.

Montgomery is recalled by generations of students for her exemplary dignity, seasoned with compassion. My favourite story retailed by Rubenstein is of a boarder who was found with an illicit bottle of Marsala rolled in her sleeping bag. As PLC maintained zero tolerance of alcohol on school premises, the girl was instantly expelled. But Montgomery allowed her to complete her year by correspondence, housed her personally during exams, rang her directly after one to see how she had gone, and was the first to congratulate her on good grades – justice tempered with mercy.

At PLC, Montgomery was also a pedagogical innovator introducing syllabi in ‘liberal studies’ and adventurously incorporating comparative religion, and ‘human relations’, including sex education. Neither endeared her to ‘Continuing Presbyterians’ who refused to join Methodists and Congregationalists in the tripartite denominational merger of 1974, and who extracted Scotch College and PLC as what might be considered the spoils of defeat, led by episcopal intriguers who would have made Obadiah Slope blush. They believed that PLC had come to offer not an appropriately ‘bible-centred’ curriculum but an ‘élitist secular education clothed in the trappings of Christianity’.

Worthy as Montgomery is as a subject of Rubenstein’s admiring glances, The Vetting of Wisdom only really develops a genuine narrative tension in the presence of her nemesis, Melbourne barrister Max Bradshaw. His photograph appears early on, fleshy and lordly, obscuring an overpowering urge to control beneath a veneer of piety and traditionalism, outwardly reminiscent of Albion Gidley Singer in Kate Grenville’s Dark Places.

Bradshaw’s clique did not sack Montgomery; rather, they ensured that her contract ended when she turned sixty. But their ‘whatever it takes’ campaign ran the gamut of harassment and intimidation, legal confrontation and media manipulation, a foretaste of the culture wars. In the middle of it up popped David McNicoll, that dreadful old Bulletin proto-Bolt, writing aslant the facts; PLC’s curriculum was impugned as ‘Marxist’, in anticipation of the parrot cry today when anyone takes a position to the left of the Institute of Public Affairs.

This enmity struck some as eerily personal. Rubenstein traces it to the 1950s, when the Montgomery sisters were parishioners at the dour Hawthorn Presbyterian Church, where Bradshaw was Session Clerk – the church’s senior lay role. Bradshaw actually attended the wedding of Joan’s sister Margaret, though she viewed him as ‘decidedly odd’. Margaret and her sister Anne decided that the Toorak parish might be more congenial.

When Joan, after returning from a first visit to the United Kingdom, also tried to move to her sisters’ new parish, Bradshaw would not grant permission, as the church required. ‘Have I been excommunicated?’ Joan chirped. Rubenstein believes that Bradshaw ‘long nursed the perceived slight of Joan’s spirited independence’, and had a ‘general disdain for assertive women in a church steeped in the culture of male dominance’.

I dare say that Rubenstein is probably right. ‘Misogynist’ has become a kind of two-dollar word for anything that would once have been designated merely ‘sexist’, but Bradshaw surely was one, and the concept of collateral damage held no meaning for him. A telling aide-mémoire concerning the observations of another barrister in chambers depicts him as a tireless schemer determined to establish a ‘bible-centred’ curriculum at PLC, come what may. ‘Parents may not like what Max has planned’, it is recorded, but ‘it doesn’t worry Max and what the parents want is of no interest to him at all, in fact Max wouldn’t worry if he had an empty school’.

There is something to the dynamic of the characters that eludes a factual retelling of events, something fathomless. In the way that sometimes happens, Montgomery and Bradshaw are comparable figures: solitary, scrupulous, driven, charismatic, frankly unknowable. Montgomery’s ouster, including Bradshaw’s role in it, could also be regarded as the making of her. Not only did it do nothing to curb her influence – no fewer than five of her staff went on to become principals themselves – but it made her story still more inspirational. The Vetting of Wisdom embodies this paradox. Had Montgomery not departed PLC as an involuntary martyr, would Kim Rubenstein have written it?

Correction

The original version of this review refers to five of Joan Montgomery’s students going on to become principals. This has been corrected to refer to five of Montgomery’s staff .

Comments powered by CComment