- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

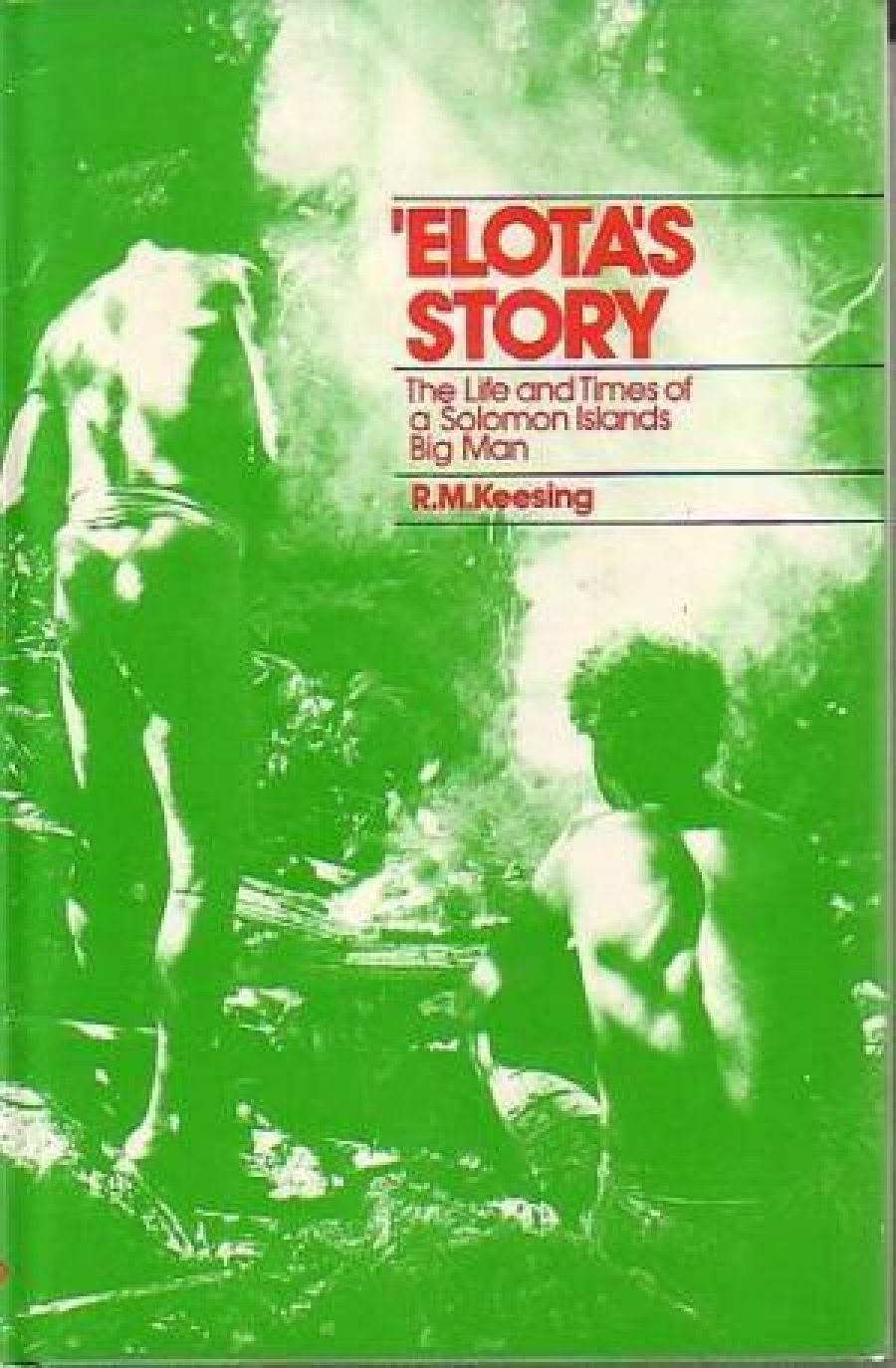

- Article Title: Olaf Ruhen reviews ‘'Elota's Story'

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A virile energetic people inhabits the island of Malaita in the middle Solomons. From the time of first contact Malaitamen were prized for their ability to work, but they had to be handled cautiously, or their inherited pride and confidence would turn them to rebellion. Those who live on the sea-coasts are readily adaptable to innovation when they can see value in it, but they abandon tradition with some misgivings.

- Book 1 Title: 'Elota's Story

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and times of a Solomon Islands big man

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $13.95 pb

The hill men in this most populous island of the group are more resistant to change. Hardly more than a decade has passed since a missionary was speared, apparently because he interferred in an adjudication of land rights. The arduous and exacting rules of the vendetta, developed here to a point at which if became central to village life, reigned with little more than token discouragement from the British authorities; in no way could these get adequate information of dark doings in the mountain valleys. Here too the curious belief in the uncleanness of women, which has influenced so much of Melanesian custom, reached its greatest intensity of prohibitions and punishments.

A tribe called Kwaio inhabits the mountains of the island’s central sector. Between the wars its men massacred a District Officer named Bell, his assistant and a dozen others of his patrol over tax collection and the seizure of illegally held firearms. After the Second World War it was here that the variety of Cargo cult usually called Masinga Lo had its staunchest adherents.

A tenet of this belief was that Americans would someday free the people from British rule. About 1969 the Kwaio heard a rumor that an American intended settling among the people in another district. They set in train an ancient six-day ceremonial to the end that he would change his destination and come amongst them.

On the sixth day Professor Keesing, an American quite new to the islands, unable to speak Pidgin, walked out of the bush. He had determined to study the Kwaio in spite of his knowledge that (in his own words) they ‘featured as the most dangerous villains and darkest and wildest heathens in the colonialist conversations of planters and missionaries’.

Results of his studies, pursued through two lengthy periods pursued through two lengthy periods of residence there, are published elsewhere. This present book is the translation of a taped life-story, told in his own words, of ‘Elota, a respected elder of his village. A curious and absorbing document it reflects ‘Elota’s calm acceptance of a life that, for man, woman or child, could end by murder at any moment, and not necessarily at the hands of an enemy. Death was the answer to an insult made publicly by a man or his relations, the answer to a breach of the tribe’s strict rules against adultery or to an affront to the ancestors; and of course each murder had to be answered in kind. ‘Elota tells of a woman killed to compensate for her husband’s adultery with one of her relations, of a mother who nominated her young son to atone with death for his brother’s fault. His tale is studded with such examples, yet permeated with a reflection of the happiness that warmed the more ordinary days of existence. He clarifies the protocol of bride-price and explains how a man can get rich through hosting mortuary feasts. Bad reproduction of mediocre photographs hardly helps the short text.

Comments powered by CComment