- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: McAuley Sans Almost Everything

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This book is a bird of most curious kidney. For the life of me I can’t see any raison d'etre for it. Not that James McAuley, with his wardrobe of fascinating hats, doesn’t cry out for a book, and not that Peter Coleman doesn’t have so many of the qualifications to write that book. But this work is not it. It’s thin, to the point of emaciation. It appears exactly four years after McAuley’s death, which, as literary biographies go, is but a day. Which puts me in mind of an Entebbe Raid or Teheran Hostages book, hitting the market while the event is still fresh. But McAuley’s career, for all its interest, lacks that brand of newsworthiness. And a book with so comprehensive a title as The Heart of James McAuley: Life and Work of the Australian Poet presumably aims to be more than a piece of ephemera.

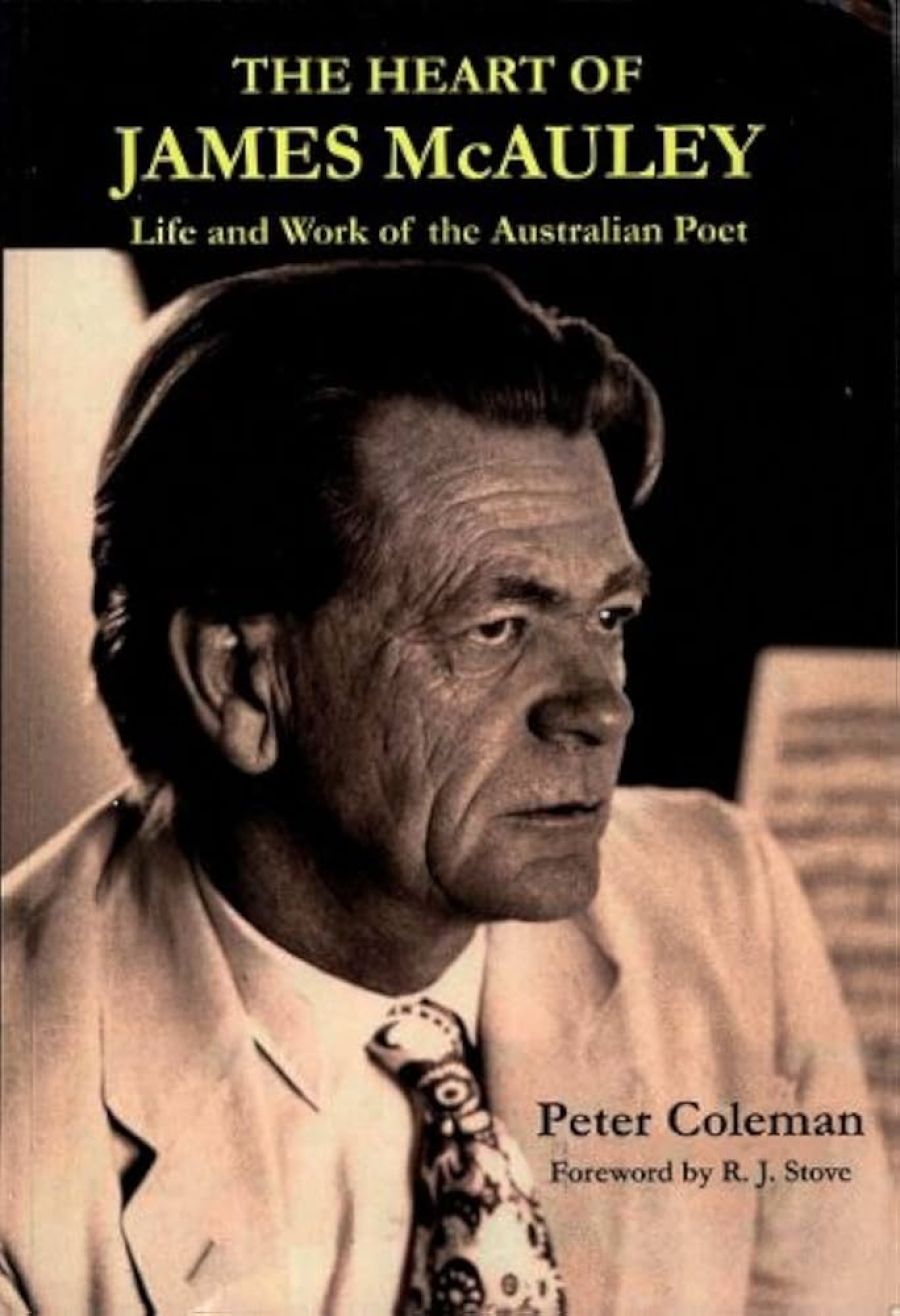

- Book 1 Title: The Heart of James McAuley

- Book 1 Subtitle: Life and work of the Australian poet

- Book 1 Biblio: Wildcat, $11.95 pb, 132 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Perhaps the book is in the nature of a crib, a one-sitting introduction to McAuley for those who know nothing of the man or his poetry but would like to redress that ignorance. But I have great trouble believing any such people exist. And even they would be dissatisfied by some of its quirks. The photos alone suggest things are not quite right. Ail save one previously appeared in a McAuley memorial issue of Quadrant. We have one photo of McAuley on his rocking horse, one of his parents, two of him at Fort Street (presumably taken within twelve months of one another), one with his wife and a daughter, one against a backdrop of wine flagons, and finally two photos of various functionaries at the Requiem held for him in Sydney. Hardly representative. Such a bizarre selection neither illustrates the text, nor provides any kind of pictorial record in its own right. What, for example, does a half-page head and shoulders of Ron Haddrick at the lectern tell us about the heart, the life or the work of James McAuley? Haddrick might scrape a guernsey amongst ninety photographs, but amongst nine!

The fundamental weakness of the book is that the very people who, I believe, would want to read it, will already know all it tells them, or at least will want a sight more than it provides. Take, for example, half of the five lines devoted to McAuley’s early youth: ‘McAuley grew up with his brother and sister in a small, brick house in Homebush, facing the Western railway line, with a fowl run at the back and wisteria on the fence.’ The last three phrases could be culled by anyone with a passing knowledge of McAuley’s small group of poems on his childhood. (In fact the dependence on the poems is so close that it is disconcerting that Coleman uses the alternative spelling ‘wisteria’ to the ‘wistaria’ preferred by McAuley.)

Yet there are a multitude of points on which we could well do with some enlightenment. Peter Coleman lists McAuley’s early reading, his school and university subjects, his extra-curricular activities and members of his circle, but there is no time for any solid analysis or evocation of personality. John Anderson was a ’major influence ... for his general style of teaching ...’ This is explained: ‘As a teacher, Anderson taught a comprehensive doctrine and the student learnt what a coherent view of the world and a creative, critical mind were like.’ This is avoiding the issue. It goes nowhere near pinpointing the precise impact of Anderson on probably his most illustrious student. Coming from another Andersonian it reads as a sad abdication of the ‘creative, critical mind.’ Nor is there any suggestion of the charismatic McAuley of the university years that Donald Horne creates in The Education of Young Donald.

The disappointing, anaemically factual is the norm for the rest of the book. Peter Coleman does tap two new major sources: the A. D. Hope papers and the Quadrant papers, and he does write interesting, if brief, accounts of the early days of Quadrant and of McAuley’s involvement with the Movement and the D L.P. But his version of this latter, ever ancient ever intriguing, political story adds very little to what can be gleaned already from a combination of McAuley’s own article on Sir John Kerr in Quadrant January 1976, and B. A. Santamaria’s ‘So Clean a Spirit’ in Quadrant March 1977, and Graham Williams’ safe book on the then-living prelate, Cardinal Sir Norman Gilroy of 1971. (What price a study of the involvement in Australian politics of Arch bishop James ‘his close adviser was a canonist’ Carroll?)

Perhaps most striking of all is the lack of any really illuminating commentary on the poetry. Of the text of 123 pages, 41, at a conservative estimate, are taken up with reproducing McAuley’s verse. This is wasteful unless the critical analysis is fresh and stimulating. But it is not. Frequently it consists only of one or two words linking the passages, and the eight page summary of Captain Quiros insults the potential reader of such a book.

In March 1977 Peter Coleman edited a Quadrant tribute to James McAuley. It included a remark by Vivian Smith on McAuley’s concern for printing standards. Apart from the curious change of wistaria, McAuley would not have been delighted by such an unfortunate lapseas ‘cholostomy’, a schoolboy howler of a translation of Justus ut palma florebit, and a collection of words between full stops on page 116 that is quite unembarrassed by either verb or sense.

Surely Peter Coleman can give us better.His McAuley Quadrant is comprehensive, penetrating and most moving. It tells us infinitely more about the heart of James McAuley than the present book. Add to it McAuley’s political last testament, with its magnanimity and humility, in his John Kerr article, and Les Murray’s obituary, ‘In Passion so eloquent in the Sydney Morning Herald ( 16 October 1976), and we have Something of substance to chew on till McAuley’s biography, potentially the widest-ranging and most fascinating of all Australian literary lives, is written.

Comments powered by CComment