- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Land of a Thousand Sorrows

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The daughter of a prosperous-enough middle-class farming family in Devon, Elizabeth Veale received an upbringing and an education that stood her in good stead during her long existence in New South Wales as Mrs. John Macarthur.

- Book 1 Title: Elizabeth Macarthur and Her World

- Book 1 Biblio: Sydney University Press, $15.00 pb, 227 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

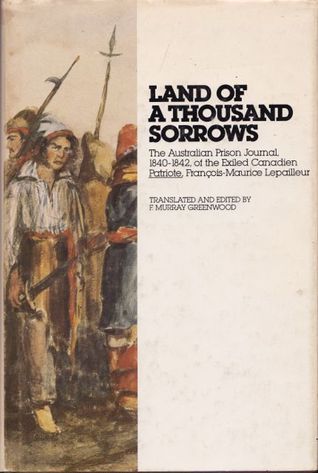

- Book 2 Title: Land of a Thousand Sorrows

- Book 2 Biblio: MUP, $25.00 pb, 174 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

This steadfastness of character was no doubt her greatest asset, but we should not neglect that her education also contributed significantly to her success, by giving her the means of accepting life in New South Wales, and of developing the potentialities that it offered.

Veale’s being able to find beauty in the Parramatta landscape, for example (‘charmingly turned and diversified by agreeable vallies and gently rising hills’), and to think, in 1795, only five years after her arrival, of New South Wales as ‘home’, reveal that imaginative capacity necessary to the successful prosecution of life in unfamiliar circumstances.

Dr King has written a very pleasant book, one based on extensive scholarship but reading easily, which chronicles the fortunes of the John Macarthur family in New South Wales and England, and especially, their rise to the enviable status of colonial gentry. She ranges easily through the intricacies of the colony's political, economic, and social development, presenting the reader with an integrated vignette of the family’s progress.

Despite her title, however, Elizabeth Macarthur is not invariably the focus of Dr King’s study, in which the activities of the Macarthur sons, especially, bulk equally as large. Indeed, at that point where we should most like a detailed exposition of the mother’s role and reality – i.e., in the periods between 1800 and 1817 when she managed the family and the estates – because crucial documents have not survived, Dr King can offer us only a little.

We do receive a stronger impression of Elizabeth Macarthur in the 1830s and 1840s, after her husband’s madness and death, but in most of the life described she is a rather shadowy figure – a resourceful but retiring woman in a world where men engross attention and leave their mark. In the end, more than of the intricacies and concerns of the everyday colonial life of such a person as Elizabeth Macarthur, this book tells us of the power of the impulse in such as her husband to obtain in New South Wales that gentleman’s country life to which he might only aspire from a distance in England; of the rapid development among this class of the sense of New South Wales's being home; and – notwithstanding – of the importance to its members of maintaining a presence in the metropolitan sphere – the Macarthurs sent their sons, when very young, to England to be educated, with John becoming a London barrister having the ear of the Colonial Office, Edward pursuing a career in the British army, and James and William becoming proficient in French and German, and revisiting England and touring the Continent at intervals.

The New South Wales that the French-Canadian patriotes transported after the uprising of November 1838 encountered was of course very different from that the Macarthurs enjoyed. Colonials themselves, the patriotes were alienated from New South Wales life by their cultural assumptions, their language, their isolation from their families, and most of all of course by their imprisonment. We may see readily enough why they should have found it a ‘Land of a thousand sorrows’.

Dr Greenwood has ably translated and edited that part of Lepailleur’s journal which covers the period of the patriotes' confinement at Longbottom (halfway between Sydney and Parramatta) in 1840-2. The narrative offers interesting details of their existence there, and of that of the small number of colonists with whom they came in contact. Sometimes – e.g., as with the details of public drunkenness, police inefficiency, and of the produce and animals passing to market – we learn too of the general life of the colony.

The peculiarities of the patriotes’ circumstances, however, rather limit the use that social historians of the colony can make of this work. The patriotes considered themselves to be political prisoners, and, as such, a distinct cut above the herd of common felons; and in other ways too they deliberately distanced themselves from colonial life. It’s hard to determine from the journal itself how much their experience of life in New South Wales mirrored the general convict experience; and in some aspects – e.g., the nature of their labour, the attention they received from the Catholic clergy, and in their commercial activities – it’s clear they enjoyed a certain privilege, a fact of which Lepailleur, for all his analysis of their situation, showed an insufficient awareness. More than about the prevailing convict experience, perhaps, or about the general colonial life, this narrative tells us about the tensions that extended confinement brings among people initially reasonably unified in outlook and purpose, and about such a group’s misery when exiled amid alien corn.

It’s the collective merit of these two works to show clearly that what one made of life in New South Wales depended as much on the personal resources that one brought to the task, as on the circumstances of one’s coming there.

Comments powered by CComment