- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Truth, Life and Death

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This volume is subtitled ‘A novel About The Nature of Truth’ and thus marks Frank Hardy’s continuing concern with basic concepts, the source matter of philosophical and theological debate, rather than with the social immediacies tat inspired and formed the texture of his earlier fiction. As with But the Dead are Many, his previous novel, a tour de force of considerable proportions in which Life and Death were set forth as interchangeable terms rather than irreconcilables, the present work is intricately structured in recognition of the complexity of the issues which is being debated, or, put otherwise, the evasiveness and obduracy of the daemon with which the writer-character is wrestling. There is certainly some sense in Hardy of being more than just interested in narrative formulae, modi operandi, recapitulative tactics. (Appropriately enough, since he writes of men in the grip of obsessions which gnaw at their intellectual vitals, and, as suggested, he stands on extraordinary intimate terms with them.)

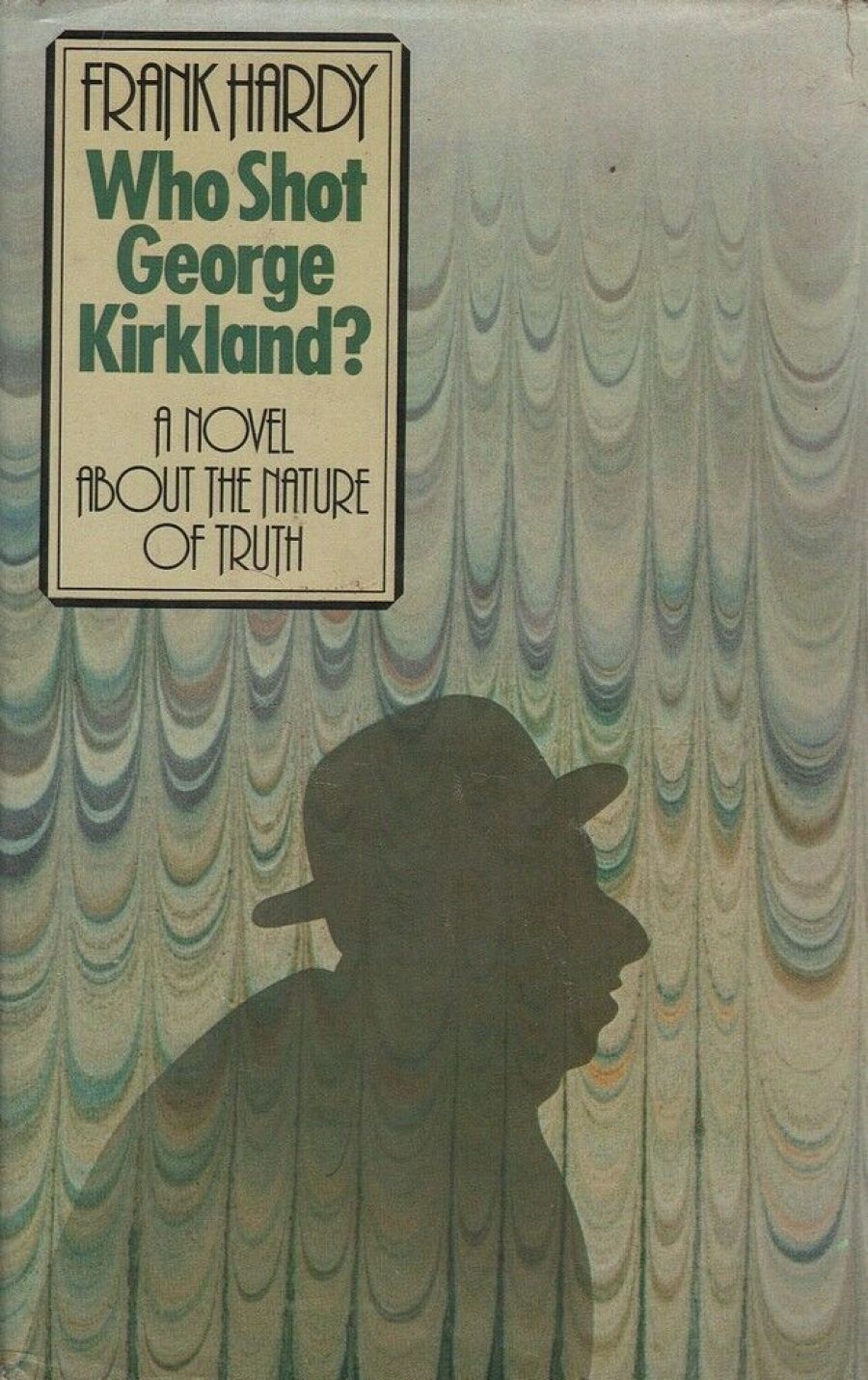

- Book 1 Title: Who Shot George Kirkland?

- Book 1 Biblio: Edward Arnold, 180p, $14.95

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In Who Shot George Kirkland? there appears, as in But The Dead Are Many, the dead man, the victim of his own hand as well as his own thoughts, speaking from beyond the grave, instructing a recorder-investigator who might be called his semi-self. Again too, an arduous and painful attempt must be made to bring into focus of those now living, events to which the dead man stood close and which occurred in the near-distance, so to speak, some thirty years before.

In the previous book, the Moscow treason trials had to be played out in memory and imagination. Here it is, (for one thing), the trial of the author, ‘Ross Franklyn’ on a charge of criminal libel incurred as the result of writing about the supposed adultery of a ‘Mrs. Nelly West’, wife of ‘John West’, villain and central figure of Franklyn’s exposé novel, ‘Power Corrupts’. The fictional (?) adultery is with a builder’s labourer and a child is born of it who dies of natural causes at the age of eight. For Franklyn, of course, referring to the famous Melbourne Trials of 1950, read Hardy, for West, who organises the charge, read Wren, and for the novel concerned read Power Without Glory. Franklyn suicides twenty-eight years after his trial and acquittal, at the end of the first part of Who Shot George Kirkland? Through the second and final part, an unemployed literary researcher, who has written a thesis on Franklyn’s fiction, attaches himself to the matter which has driven the author into a delayed depression, state of guilt and then suicide, the truth or falsity of the Nelly West adultery episode. This, Franklyn had claimed, was the one aspect of his realist novel that he had not himself researched and based upon proven fact. He had, instead, included the story on the word of its recounter, a dubious figure named Alan Hall. Having struck a barren patch half through his manuscript of Power Corrupts¸ the younger Franklyn had found that inclusion of Nelly West-Bill Egan material gave impetus to all which had to follow, the later fats of West’s villainous career. The younger researcher, never named, has not only to bring alive Franklyn, using the latter’s last notes, which he finds at the scene of the suicide in a south of France hill-top village. He must also, following where Franklyn had led, try to bring into focus the shadowy figure of the deceased Alan Hall. He does this by following a twisty trail to Hall’s past dwelling, to his widow and his psychoanalyst son, through rather dowdy Melbourne inner suburbs.

The attention to detail, on both author’s and fictional researcher’s part, in this latter section is first class. So too, in terms of fictional satisfaction, is the conclusion to which researcher and reader, one as wrung-out as the other, are finally drawn. The question of the historical actuality or otherwise of the Nelly West-Bill Egan adultery becomes inextricably mixed in the minds of both West and his biographer-to-be with that of Who Shot George Kirkland? For reasons that I am happy again to pronounce as fictionally ingenious.

I am applauding overall, the fictional force resident in the narrative ground plan. In the actual dramatics though, there’s insufficient intensity for long passages, with the authorial attention fixed on marginal social matters or given to arduous exercises in inductive thinking of an unfleshed sort. It is, of course, twilight territory which Hardy, a fictionalist of mature power, has chosen on this occasion to visit, and it can be allowed, (rather charitably), that the flickering effect persisting through the narrative is a necessary aspect of the operation. Certainly the uncertainty which both Ross Franklyn and his biographer feel about the book’s central character ensures that Alan Hall, who first told Franklyn the adultery story (as well as several others of a not-quite-unbelievable sort about his own life), is a genuine man-of-mystery. The living Hall who visits the younger struggling Franklyn has a quality of remoteness; and contrary-wise, when the parts begin to jell for our researcher of Part Two, the long dead Hall comes up from the pages of period newspapers, and other sources as a vital presence. He is the suitable centre piece of a novel about intellectual uncertainty.

Had Hardy been concentrating full force on writing a mystery documentary then Alan Hall, the walking question mark, plus the ingeniousness of the plot line may have ensured its success. But he wasn’t. Rather he sees his labours as aimed, fundamentally, at philosophical definition, the ‘nature of truth’ so we are told, with all the above ingredients merely contributory to what seems at best no more than a verbal triumph, one rather more easily won than Franklyn’s self tortures and his biographer’s halting dialectics might suggest. Here are Franklyn’s last thoughts after overdosing on sleeping tablets:

Does an exploration of truth through memory lead to a truth other than that which it sets out to tell? Does it create a tension between fact and fiction, life and literature, which opens the door to deeper levels of understanding?

And here is the young researcher, in the concluding pages, musing upon the truths to which the dead author has led him:

Literature looks like but can never be a record of actual experience. For when a writer recalls events whose basis in in persons other than himself, those persons are transformed as he recalls them and enter the realm of art…(And) when a writer recalls his own experience, explores his own memory of himself, he is also transformed completely.

The insertion here of the word ‘completely’ might lead a comatose reader to snap out of the comment ‘Nonsense’! Otherwise, of course, there’s no desire to react to these laborious generalisations (though one might answer ‘More or less’ to the questions). It’s all rather like looking up at the stars painted on the ceiling of the old State Theatre. There’s not really much there to invite a positive response.

Too large a part of the novel consists in the evocation of just such a metaphysical space, and then, in contradiction of that, in casting about for social data, often a marginal relevance only, with which to people the void. The hefty material detail of how the exposé novel was printed without John West’s and his henchmen’s knowledge is laid out, as are glimpses of glamour figures with whom Ross Franklyn mingled and sometimes got entangled around the Vence valley before his suicide. A third overall intention, nosing in between the others, then, seems to be to create the posthumous fame of Ross Franklyn as Aussie raconteur, bawdy tongued radical, lure of sinuous bright finned European beauties, and novelist ‘whose greatness lay in his obsessive belief that verity is born, and all literature belongs, in the mysterious border region between imaginative and empirical truth’. The contempt revealed here, as in the other quoted extracts, for philosophy as anything like a strict intellectual discipline rivals the same ‘Franklyn’s’’ contempt for psychoanalysis and for its founder father, ‘Siggy’ Freud who ‘screwed up half the women in the world’. The fact that Franklyn’s creator, Frank Hardy, uses his own rough cast interpretation of Freudian motivations as ballast, to keep the narrative afloat is one among other contradictions. And, since this sort of slack easy-handedness tends to spread, we find contradictions occurring in the area of the novelist’s own professionalism. So that the research student of Part Two, though he lies ‘on the (St. Kilda) beach with my latest lady, saturated by sun, surf, sand, sex – and smoking pot’, a typecast contemporary sort of guy, is yet capable of musing upon ‘the young ladies in St. Kilda Road from the offices which had invaded the stately homes opposite the gray Cenotaph who joggled their breasts and bums in tune to their tapping heels’. He things, such anatomical detail plainly suggest, not in the mode or idiom of the sexually liberated at all, but in the manner, at once lewd and deeply suspicious, of a sixty year old survivor from the days of sexual puritanism! The two grammatical solecisms detectable in the same passage are typical I am afraid. A reference, earlier on, to the ‘defending councel’ could be the sort of boo-boo that gets through even into the King James Bible, except that here it becomes one item of a prevailing and many tiered slackness.

My feeling is that Who Shot George Kirkland? was hurried to the publishers at the mid rather than the terminal point of gestation. Hardy hasn’t quite seen where the real strength of his material lies. I think he should have fixed just much more centrally and extensively on the real question which is, of course, who shot George Kirkland. Certainly when there’s adequate attention given to this matter then the self indulgence, with philosophical concepts and sleeping tablets alike, gets put aside and we’re back in that finely shadowed, echoing area of half truth where the author of But The Dead Are Many is at his impressive narrative best.

Comments powered by CComment