- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The least beautiful of lies

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This collection of stories put me off from the first page. In the opening paragraph there is ‘an exuberant kelpie bounding’. The second paragraph outdoes that, presenting seagulls as ‘wheeling and screaming’, in search of ‘a reeking fish head’. We already know that ‘the life was lonely, but it was peaceful’. Clichés enlivened by irony or just some simple surprise of context proves useful tools in the hands of a good writer. But Julie Lewis, on the evidence of Double Exposure, is not a good writer and cliches are offered up to us without any apology. Much of the problem seems to be that she overdoes adjectives and adverbs:

She felt for a pulse. Feeble. She gingerly touched the stubbly cheek It was bruised and there was a gash on the forehead. His clothes, seaman’s wear, were soaked. She studied the unconscious form. He was fairly young, about thirty, she thought. Looked a battler. She smiled ruefully and gently lifted the lock of hair that had fallen across his brow. It was matted with blood. (‘Flotsam’, p 2)

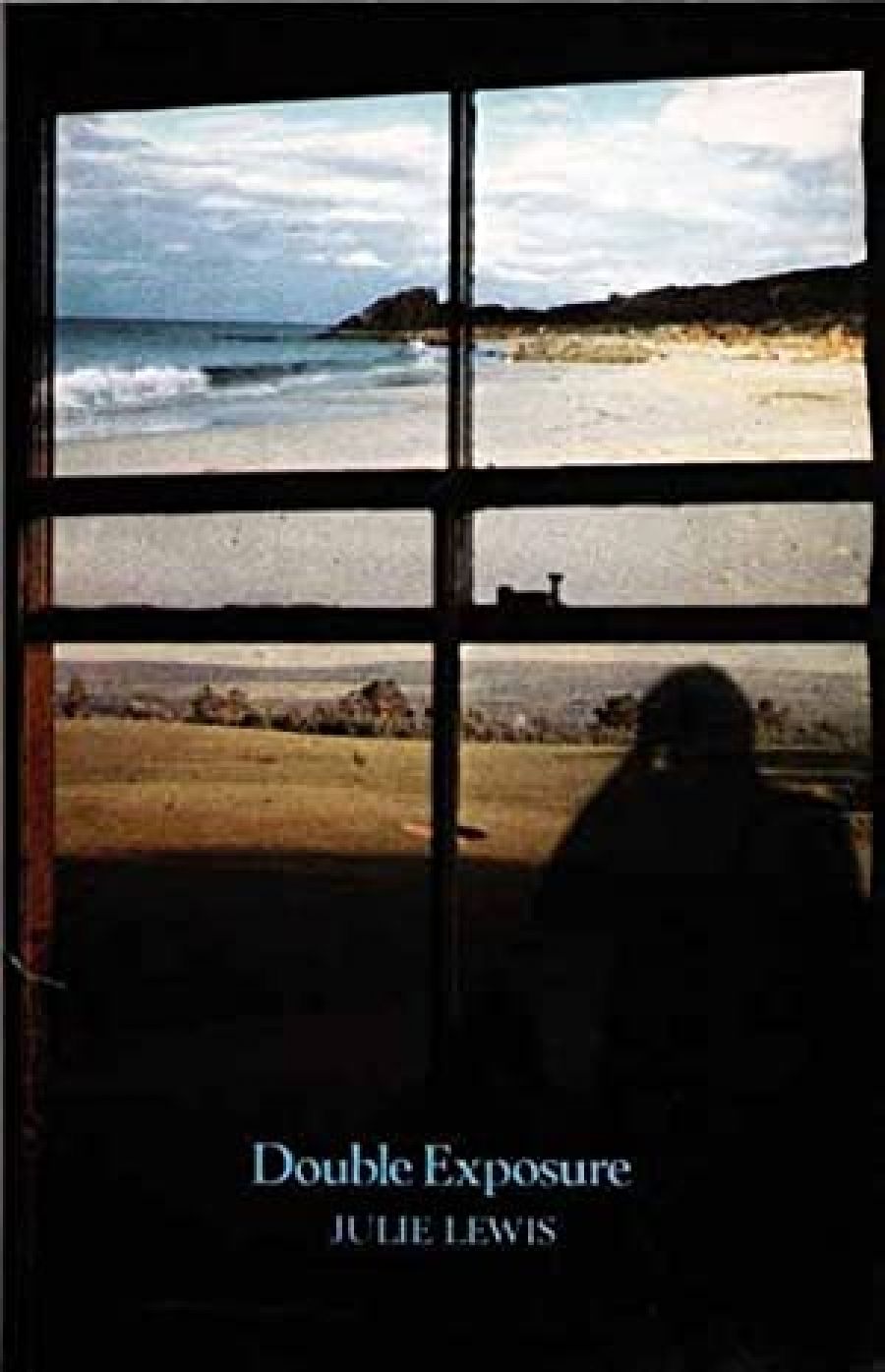

- Book 1 Title: Double Exposure

- Book 1 Biblio: Fremantle Arts Centre Press. 96 p ., $5.75

There is a disjunction between the pleasant storytelling tone and rhythm of this string of familiars (‘stubbly cheek’, ‘smiled ruefully and gently lifted’) in an ill-sorted mixture of conventional and ungrammatical sentences and the nature of what is being described. So, it is no surprise when we are told the wounded man receives attention from ‘firm, sure hands’ and that the woman works on him ‘with detached skill’. Unfortunately, ‘Flotsam’ is typical of the stories in this volume. Awkward, cliched phrasing and obvious contrasts distract attention from the storyline.

The title of the collection is taken from one of the stories. A painter feels exposed when she attends the first exhibition of her work and hears the way people talk about her painting, ‘But it’s bits of me that’ll be hanging there. Bits of me!’ In a marginally less stereotyped way, the art patrons (and the gallery director) are exposed too, ‘Don’t give a stuff for art. It’s marketable’’. Such dichotomies shape nearly every story in Double Exposure. ‘Tutorial’, for example, treads the ancient ground of showing us how vacuously pretentious university tutorials may be and how students often feel confused and alienated. But I am left with the impression that Julie Lewis believes she has the entire tertiary game summed up.

Most of the stories run the theme of a double exposure: one character pitted against another whose worldview is utterly different. But there is no dialectic at work, because no-one budges. The characters rarely transcend the barest stereotypes and all that keeps us interested is some cleverness of plot – despite the badness of Julie Lewis’s prose. I found myself interested enough to finish every story. I wanted to find out what would happen. Often nothing did, and I found the failings in those stories most blatant because they were undisguised by any liveliness of plot. ‘A Day in the Country’ is probably the worst short story I have ever read (yes, including Mills & Boon). Three upwardly mobile suburban couples visit a couple living on a farm. Just for a start, the names of the three pairs of visitors are Jerome and Vanessa, Nigel and Romona, Anthony and Fiona. Jerome and Vanessa have friends named Montaigne. When they arrive, we are treated to nearly every cliché of farm life. One sentence seems to have been lifted straight out of The Tree of Man (remember Dudley Forsdyke’s discomfort on the farm?): ‘Anthony, more at home selling broad acres than strolling through them, stepped into a newly dropped cow-pat and completely ruined his Hush Puppies’. The double exposure is unconscious: Julie Lewis’s conventional, merciless ideas about upwardly mobile people and her naïve endorsement of what can only be summed up as rustic pleasures. What is so disturbing about fiction like this is that it remains fiction in the narrowest sense of the term. In dealing solely with caricatures, the author encourages her readers not to look further: unquestioning distinctions are reinforced; boring and obvious themes are perpetrated. These are the least beautiful lies.

The lack of freshness in the narrative makes for mawkishness where otherwise there might have been pathos. Overdrawn contrasts lead us to ask such questions as: ‘how did this couple come together in the first place?’. If there are goodies and baddies, then female figures are usually the former: most of the men are boorish and/or timid, while the women tend to be sensitive and open to new experience. Julie Lewis seems uncomfortable with vernacular and the dialogue of her characters is stilted and jerky.

‘Withdrawal Symptoms’, the final story in the collection, is also the least bad. As well as traces of wit, there is inventiveness. A competent character sketch of an ageing physical education teacher is nearly spoilt when Julie Lewis tells us he is ‘a coiled spring, quivering with tension’. The novelty is the inclusion of some convincing handwriting in the text. But even in this rather charming touch, there is one disturbing aspect: why couldn’t the author have conveyed the nature of the character, and the characters, through her own prose?

Comments powered by CComment