- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthologies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The title of The Half-Open Door implies questions relating to the lives of modern professional women in Australia, and bears on the current attention, political and academic, being given to women’s matters. These questions are made explicit in the book’s Preface, which asks why women enter the demanding areas of the professions and the arts, and why so few achieve positions of high status in these fields. Contemporary evidence, formal and informal, of the ambiguity of opportunity for women in Australia is commonplace. For instance, the typical composition of academic humanities departments is like that in which the reviewers work: sixty-four per cent of the student body yet only twenty per cent of the full-time academic staff are female. Why the door – which was opened relatively early for women in Australia by university admittance, emancipation and equal job-opportunity –remains half-closed is a question that needs to be asked. Regrettably, this volume goes only half-way to suggesting an answer.

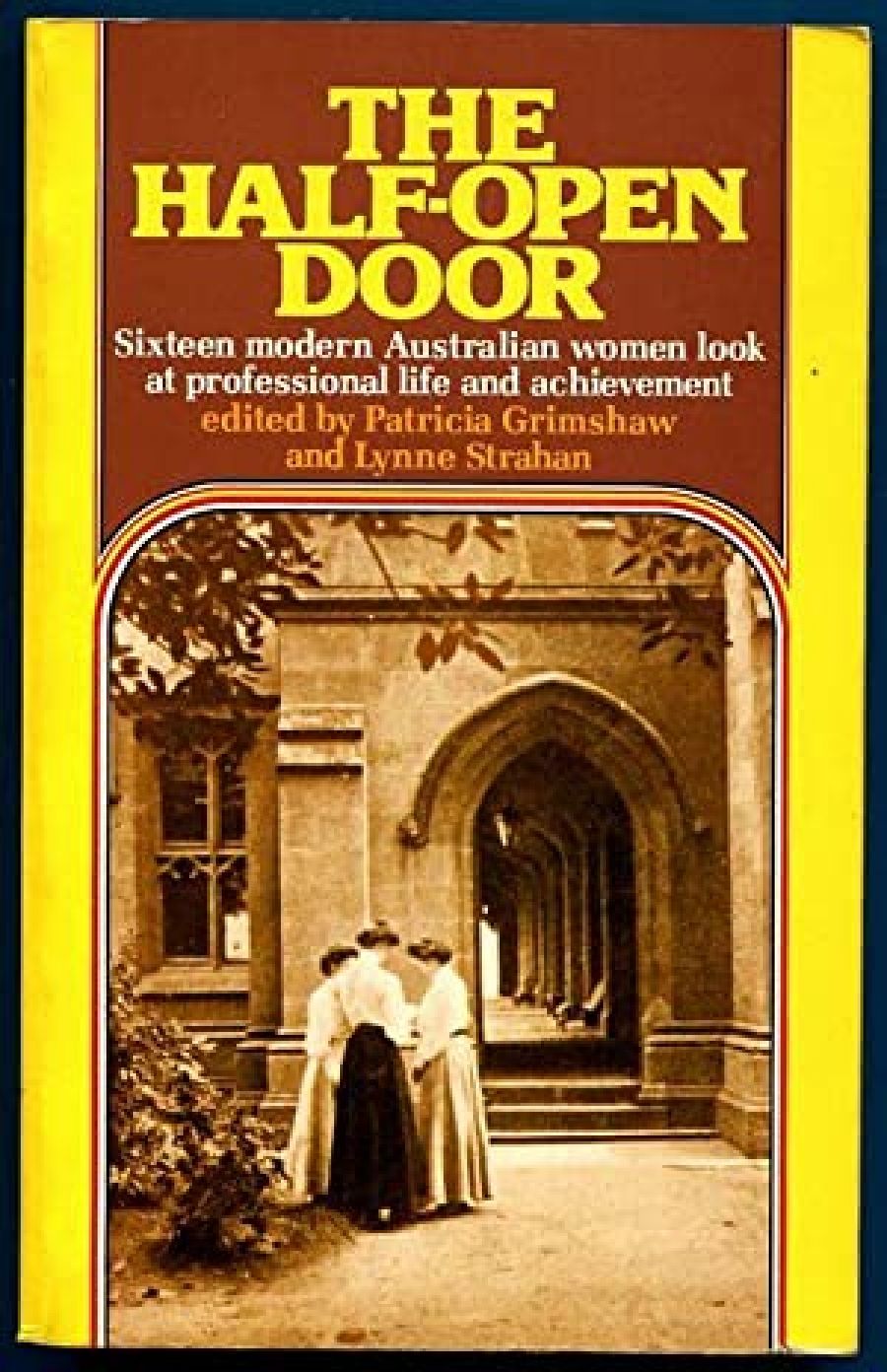

- Book 1 Title: The Half-Open Door

- Book 1 Biblio: Hale & Iremonger, 344 pp., $24.9 hb

The Half-Open Door asserts and explores this question by collecting the personal reminiscences of sixteen Melbourne women who have achieved recognition in the professions and the arts. Each piece is introduced by a brief biography, establishing its author’s personal and professional history and is accompanied by an attractive sketch by Sandra Simon and a few well-chosen photographs. We are told in the Preface that contributors were asked ‘to reflect on their lives, and attempt to relate for others the most significant formative influences on their lives’: and one contributor defines the theme of the book as ‘the lot of women in professional and artistic life in Australia’, and its aim ‘to cast some light on the subject by drawing on the experiences of a selection of such women’. This freedom of expression within a broad theme and tentative aim leads to a similarity of structure among the pieces: narrative of childhood, summary of school and professional experience, and analysis or evaluation in terms of being female. Thus, the book attempts to fill what its editors perceive as a gap in women’s social history in the twentieth century, which lacks the personal diaries and reminiscences preserved and currently being recuperated from the nineteenth century.

The book does help fill this gap, but it doesn’t finally succeed in doing what it sets out to do: to elucidate the metaphor of high achievement for women in Australia as a half-open door. In part this is because the nature of the material collected here does not pretend to be representative. Brief lives of sixteen mostly middle-class, mostly middle-aged (only six were born after 1930) Melbourne women cannot reflect the full spectrum of women’s professional life in Australia today. Studies in the late 1960s which showed undergraduates having difficulty projecting images of successful women could not be reduplicated in the late seventies. And the youngest contributor indicates that new models of marriage and family life may be as important a positive influence as the patterns of natal family life focused on here; she remarks that the ‘virtual absence’ of husband and children from her account in no way represents ‘their importance in my life, nor any lack of recognition on my part for their tolerance and support of my attitudes’.

But more importantly, the book’s central motivation, to discern ‘the limiting parameters of women’s entry into and participation in this [the traditional male professions and arts] arena’ falters because of an insufficient or insecure methodology. In her Introduction, Patricia Grimshaw identifies her methodology as oral history, ‘an attempt to restore the past in all its fullness, in its particularity, as a counterbalance to academic history’s often anaemic and even inhuman intellectualisations’. But even oral history cannot recover ‘the past in all its fullness’: and although this arbitrary collection of life stories may be valuable evidence to ‘help the present to understand itself by reference to history’, it does not in itself constitute that history. To do so, these accounts must be interrelated, analysed and evaluated in terms of the questions asked. At some point the oral historian, like the academic historian, needs to intellectualize her material, though there is no reason that she shouldn’t do so in a robust and human fashion.

Any historical study formed by what one contributor, historian Kathleen Fitzpatrick, calls ‘a process of discovery’ is only possible if material is selected according to a particular process, or if valid generalisations are thoughtfully drawn from that selection of material. This Introduction does indeed provide generalisations as to the reason for women’s qualified success in the professions and arts, but these are familiar, and drawn with little reference to the evidence provided by the ‘totally idiosyncratic’ individual perceptions which make up The Half-Open Door. This publication will inevitably be compared with Jan Carter’s recent study, Nothing to Spare (Penguin, 1981). Carter taped interviews with a series of aged, Western Australian pioneer women from a wide social spectrum, who are tellingly delineated only by their father’s occupation, and united by the perspective of their age. As oral history, that work’s methodology, aims and implications are carefully outlined in its Introduction. Arguably, what is gained by the individuality of expression and perspective in The Half-Open Door is lost in the generalisation and want of a coherent overview.

It is the reader of The Half-Open Door who must engage in the process of discovering that the ‘patterns of experience which tell us something of the necessary conditions existing for high achievement in women this century’. Patterns do emerge. Fourteen of these women were university educated; the remaining two – an artist and an architect – trained at technical colleges. Eleven attended private secondary schools, so presumably were positioned for university entrance. Frequently they comment on the inadequacy of their secondary education, even while singling out the influence of an exceptional teacher of two. ‘Like most girls of my generation,’ comments Fitzpatrick, ‘I was dumped into the twentieth century so intellectually crippled I could scarcely comprehend the world I was to live in.’ Usually they compensated by an unrestrained, self-educative addiction to reading: ‘books saved us’, says music historian Therese Radic. Sometimes (as with educationist Barbara Falk, and historians Alison Patrick and Diana Dyason), this reading was fostered by parents; in other cases it was a private passion, serving as a mode of rebellion (Radie); identification with stereotypic female roles (writer and co-editor Lynne Strahan); or rejection of such roles (feminist activist Beatrice Faust).

Most of these women see themselves influenced by mothers or female relatives, who either imposed stereotypes by example or precept (‘men don’t like clever women’, warns Patrick’s mother), or establishing role models through their feminism or lack of conventionality. They also stress the influence of their fathers, most of whom approved or encouraged their daughters’ education, though with little or no view of that education as career preparation (paediatrician Dame Kate Campbell’s father is the only apparent exception). Instead, the implicit expectation of these women, by parents and often by themselves, is that their intellectual training will eventuate in marriage. Theirs is not a society or an ideology which allows feminine sexuality and achievement to be easily reconciled.

A few chose not to marry. The majority who married and had children speak eloquently of the difficulties of fulfilling two roles. However supportive and helpful their families, their careers typically were interrupted by childbearing, hampered by housework, and dogged by the conflict and guilt of trying to be both nurturer and worker. To this was often added the frustration of entry into the job market through exploitative part-time positions. Given the choice between career and family that some of these women felt constrained to make, and the difficulties faced by those who chose both, what is remarkable is the balanced, unrecriminating retrospective view they take of their past decisions and conflicts. The tone of the concluding remarks of possibly the least advantaged of these women – Beatrice Faust – is representative; speaking of the dual message to both achieve and to not achieve which she, like all of these women, received from her society, she says: ‘I have used a lot of energy trying to reconcile the two and I think I’ve been able to do this because I’m a survivor by temperament … and – overall – I’ve had quite a fair shake.’

In the end it, is the dual messages these women grew up with which emerges as the chief force militating against success as measured by achievement in traditionally male spheres. Falk speaks of a consciousness of being plain as a motive to academic achievement; Radie of a second self who is afraid and will disappear unless a male confirms her existence; publisher Joyce Nicholson of her relief at learning late that ‘I was not peculiar or odd but had simply been forced into one way of life, by society’s attitudes’; Patrick of being devastated by the discovery that ‘my one acknowledged asset [her intelligence] was now to be taken as a social handicap’; and psychologist Norma Grieve of the ‘question of femininity’ as having been ‘for a long time separate from the active, achieving part of my life.’

Grieve goes on to identify ironically the masculine ideology that, on the one hand, accedes to feminine achievement and, on the other, ascribes to women the qualities of submissiveness and passivity, and confines them to biologically defined domestic roles: ‘Men’s experience is characteristically attributed to hard work and intelligence. Women’s success is explained by chance and good luck.’ Margaret Mead made the same point when she observed that in our society success sexes men and desexes women. Such an ideology also blurs options, discourages self-direction, and fosters a fragmentation of energies; these women struggle against its implications. An overwhelming impression formed from reading these essays is that Australian women’s lives lack the single-minded, unequivocal aims of men’s. ‘Too many of my years were spent following false trails,’ Nicholson acknowledges with regret. The essays which make up The Half-Open Door attest to the exceptional talent, hard work and courage which has been necessary for women to achieve qualified success in a chosen profession in twentieth-century Australia; perhaps as a record they may serve, as Faust hopes, as a contrast to more common female experience, to ‘free them to ask a few questions about women who break free from the traditional role’.

Comments powered by CComment