- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Religion

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Beauty and Desolation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The dawn and the evening of the world, alike, are seeding-grounds of myth and archetype: the distant past, when chthonic Ancestors are imagined to have emerged from a landscape of rocks and dust – the post-holocaust world of the future, where a landscape of rocks and dust is imagined to have emerged as fruit of hidden and poisonous seeds within the human psyche.

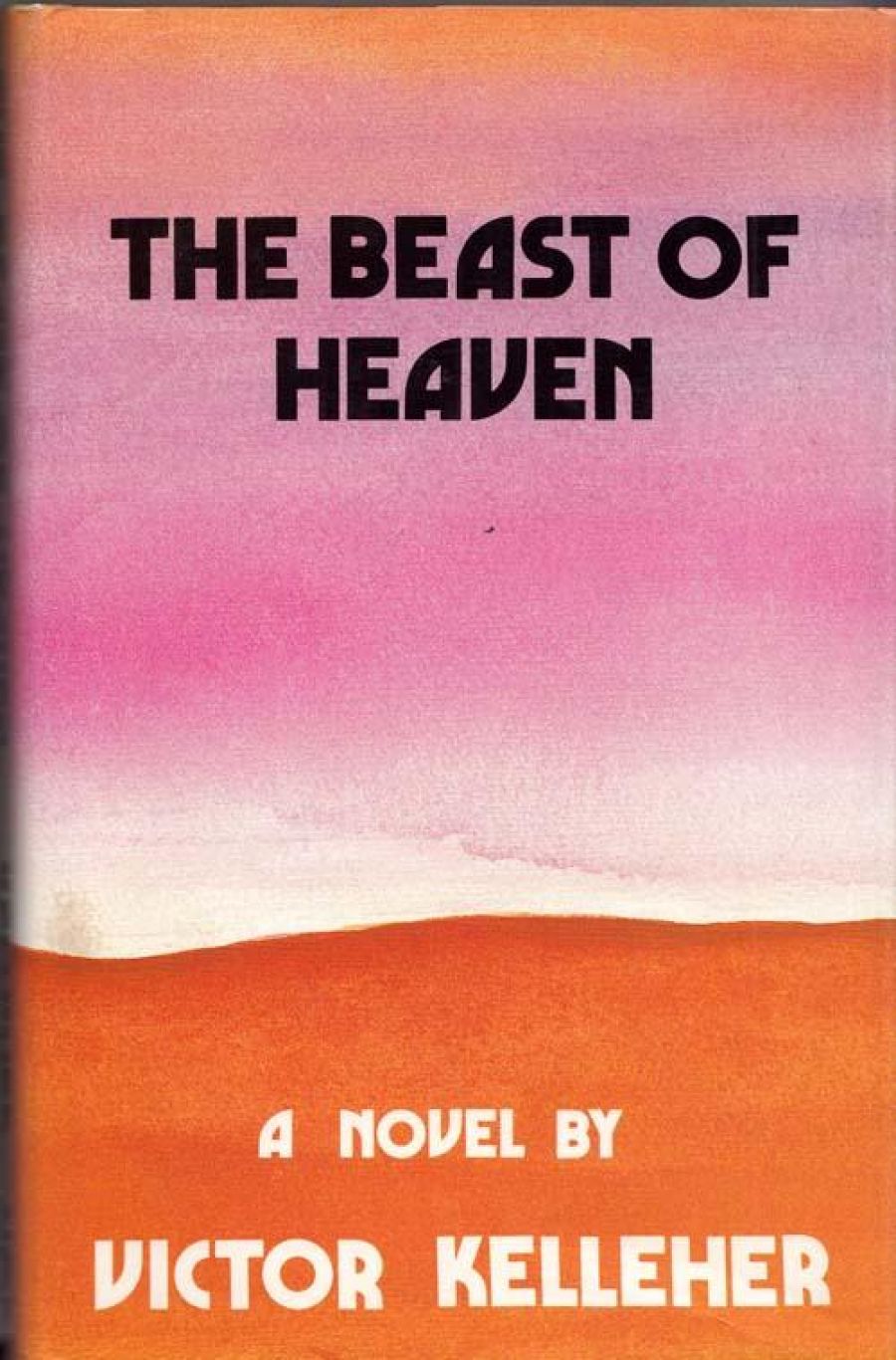

- Book 1 Title: The Beast of Heaven

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $10.00 pb, 205 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Across the windswept rocks and dust of the plains, in Victor Kelleher’s The Beast of Heaven, a small band of Gatherers wanders in search of sustenance and shelter. A hundred thousand years have passed since the nuclear holocaust of 2027; a hundred thousand years of unremitting thought, in conditions of complete sensory deprivation, for the two Artificial Intelligences (computers A and Z) whose underground abode the Gatherers are approaching.

Like angel and demon, computers A and Z have become each the pure essence of some principle at the root of human psyches – reduced, in the course of their long torment, to the archetypal personalities on which they were based when first programmed to decide whether to release the nuclear device which is still maintained in readiness for the resumption of their debate. They are to decide on the basis of a reductivist image of humanity, having debated the ‘distinguishing feature of human history’.

However, as Kelleher is well aware, humanity's best qualities need not be the ones which are unique to humanity. Co-operation, affection and altruism, for example, are virtues which many animals share; whereas a very unexpected image of ourselves can be obtained by isolating truly exceptional traits. One philosopher (Mary Midgley, in Beast and Man) suggests as examples the ferocity which ‘man has always been unwilling to admit’ and the preoccupation with sexuality which sets man apart from the supposedly profligate simian brute: ‘Gorillas, in particular, take so little interest in sex that they shock Robert Ardrey; he concludes that they are in their decedence’.

The reductivist programmers are now ‘the Ancients’ of the Gatherer mythology – beings who were all goodness, who prepared the world in constant thoughtfulness for the Gatherers’ well-being, and even provided the raging Beast of Heaven to remove Gatherers whose lives were ‘complete’. The huge horned Beast is the Houndin, a dust-eater with hands, maintaining in its clouded intellect an utter intolerance of all life independent of itself.

The Gatherers re-activate the computer-debate, the Beast is present at the moment of decision, and the reader’s interest is held superlatively, with the final dreadful answer to the question both of Gatherer and computer rendering ironic many of the reader’s former perceptions of irony.

The reductivist answer may inject poison into what formerly seemed the purest excellence of playwright and poet; but the spirit of the book itself is counter-reductive. Genuine myth and genuine surprise achieve themselves amid an eery wreckage: ‘the long stretches of yellow-grey earth, reduced to fine dust and blown into undulating patterns by the wind – desolation fallen as though by accident into the unlikely lineaments of beauty’.

Comments powered by CComment