- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Serpent’s Tooth is a massive, sprawling novel. It is panoramic in its vision of twentieth century social and political history, and meticulous in its rendering of one man’s struggle to sustain the mighty ideal his father has inspired in him.

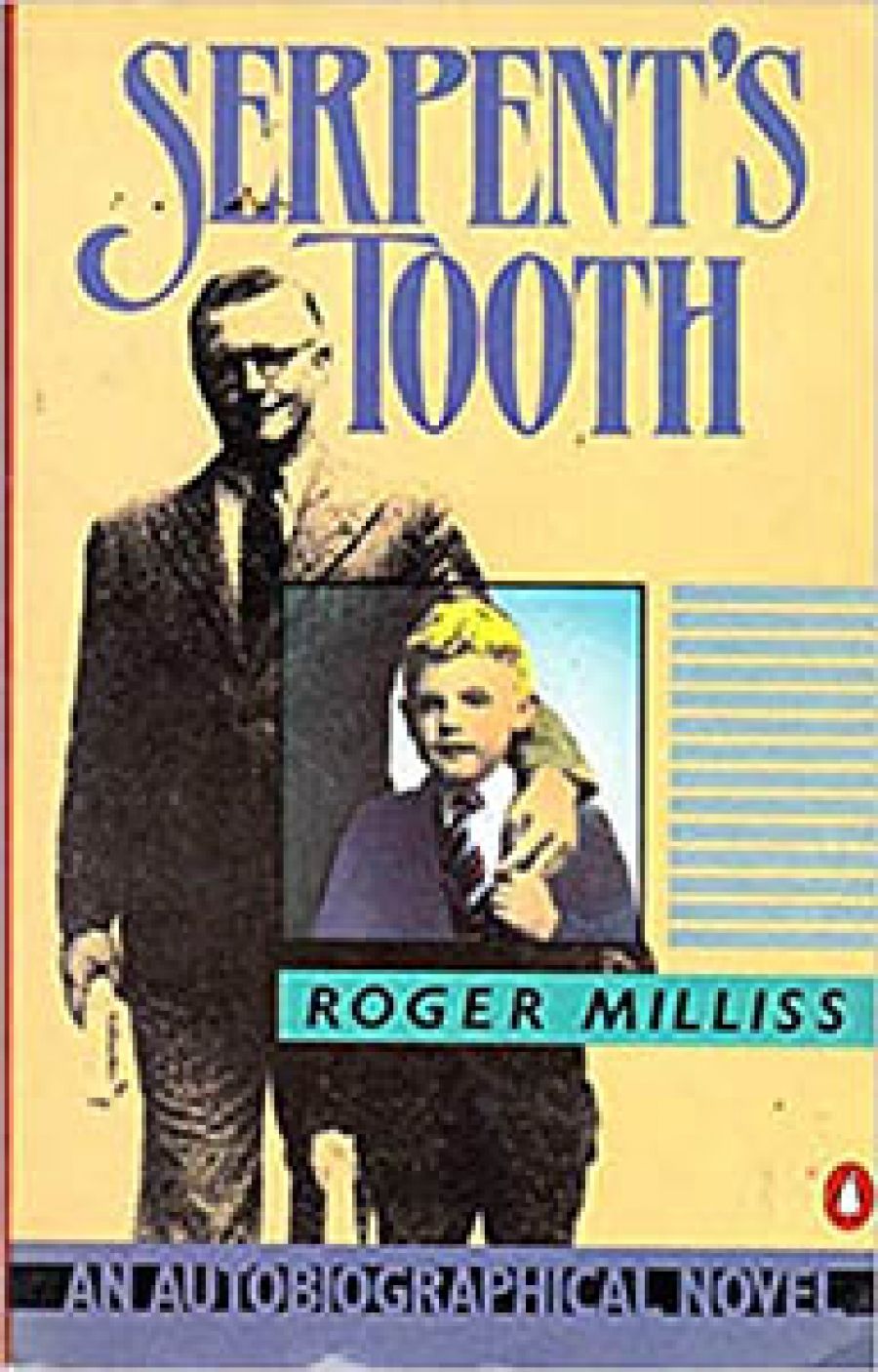

- Book 1 Title: Serpent’s Tooth

- Book 1 Subtitle: An autobiographical novel

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, 481 pp., $9.95

The book is an intensely passionate account of the debt Milliss owes his father, a plea for recognition of a father’s love and wisdom. At a deeper level it is an agonised confession of filial ingratitude, and an implicit attempt to vindicate his father’s memory.

The book will be affronting, even forbidding to many readers. Some may even see it as a relic of modernism, another tiring instance of something Joyce has to answer for. Its physical presence is striking. It is very long, and although it has sections and chapters, there are no paragraphs. It is an overwhelming sight, veritable slabs of print. Apart from ordering the development of a narrative, paragraphs, especially in a long work, are convenient places to pause, to reflect, to anticipate. Milliss’s prose allows us no such luxury.

The appearance of the book, then, is certainly ominous. Abandon hope all ye who enter here? Quite the opposite, in fact. The experience of reading such relentless prose is liberating rather than harrowing. Serpent’s Tooth isn’t a conventional novel. It is an autobiographical novel. There is a difference. It doesn’t tell a story. It offers us a first person narrator, from whom the entire flow of words issues, like the ‘cataract of change’ which he chronicles with such detail.

It is through Milliss, as the speaker, that the whole work is focussed and restrained from swirling into incoherence. His prose flows on with the easy rhythm of a meditating mind, reflecting on his family’s place in Australia’s development as a nation amid the change and turbulence of international politics and social history. His thoughts and reflections are fleeting. It is a fast moving novel, often rather like a ticker-tape of incidents, trivial and momentous.

It also has slower, softer moments of recollection, of indelible childhood memories, or of gentle intimacy, which stand out against the often cruel backdrop of the Depression, World War II, or Vietnam.

The novel commences with a collection of fragments, relics of Milliss’s parents which he is sifting through after their death. And with a tireless calm, Milliss proceeds to retract from these fragments his family’s history, and eventually his own development under the tutelage of his beneficent father.

We are taken through his childhood in Katoomba, his university education, where he develops his commitment to the communist cause, and a lifelong interest in theatre and literature. We go with him to Russia as a journalist, and we are privy to his important assessment of Russia as the ‘citadel of socialism’, and the possible application of the socialist ideal in Australia.

In making a connection with Russia, he appropriates his father’s establishment of a tea trade with Communist China and a film concern with Russia, promoting the Russian cinema in Australia. He is very much his ‘father’s son’, bearing the reproach and intolerance of a conservative, anti-communist public (‘best known Com in town’), all the while pursuing with single-minded determination the ideal of radical social change.

Dissent, however, works its destructive way into their lives when their loyalties are divided by the Sino-Soviet split. Milliss senior retains a firm commitment to the Chinese, and their personal conflict reflects the larger schism in the Communist Party in Australia. They are driven further and further apart.

After his father’s death Roger realises, with overwhelming bitterness and guilt, the bullying ingratitude he has shown his aged and infirm father, having trampled on his beliefs and repaid his guidance with betrayal. Australia is very much ‘The Lucky Country’, another outpost of complacent Western capitalism.

The book does, however, suffer for its powerful personal vision. Its virtues often become excesses. There is often such a proliferation of detail that remembered experience becomes an imbroglio of miscellanea which has little or no impact. Milliss has a tendency to sentimentalise his affection for his father into an overbearing idolisation, or wallow in the mire of self-reproach in ways which are often irritating and melodramatic. But such is the price a novel of such personal intensity has to pay.

Comments powered by CComment