- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Looking at our art of the 1970s

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Remember the 1970s? They are already the subject of an anthology of critical writings in Australian art compiled by Paul Taylor. Modestly described on the back cover of Anything Goes as “Australia’s most written-about art critic”, Taylor has assembled some 16 pieces of previously published criticism from magazines, newspapers and exhibition catalogues. In this anthology we meet most of the big names of the seventies’ art criticism in Australia: Terry Smith, Patrick McCaughey, Margaret Plant, Daniel Thomas, Janine Burke and others. Donald Brook’s often turgid writing on PostObject Art has been omitted though I seem to remember that his criticism was considered important and influential at the time.

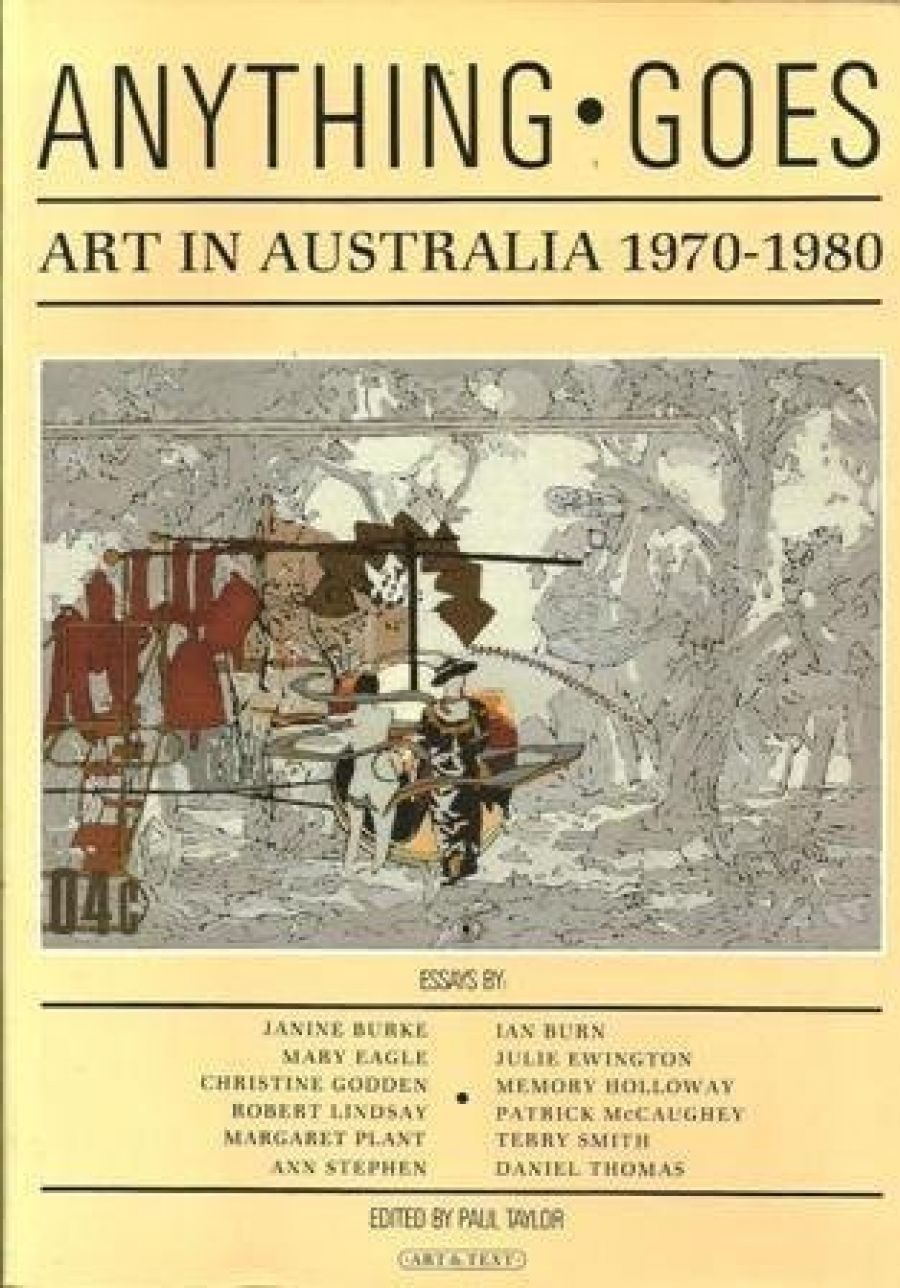

- Book 1 Title: Anything goes

- Book 1 Subtitle: Art in Australia 1970-1980

- Book 1 Biblio: Art and Text, 171p., $29.95, $19.95 pb., 0 9591042 08

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Rather than attempt a survey of the work of a number of the most prominent artists, Taylor has focused on the major critical debates and issues that surrounded – and in some cases motivated – the art produced. Anything Goes provides a suitably representative discussion of the seventies’ major art activities, painterly abstraction, minimal art, conceptual art, body art, art photography, feminist art, political art, community-based art and other forms are all included. Yet by the late seventies, as Mary Eagle suggests in her article ‘Ideologies of an Art Revolution’, it made more sense to view this bewildering array of art activities as different responses to issues and ideologies rather than as distinctive art styles. Stylistic continuity had broken down as artists ‘increasingly found their sense of collective endeavour in ideologies’.

What were, then, some of the issues in the art of the seventies? During the early part of the decade, Patrick McCaughey and Terry Smith were like knights on chargers fighting out the issue of internationalism versus regionalism. McCaughey’s catalogue introduction, ‘Ten Australians’ of 1974-75, lauds the “maturity” of a group of painterly abstractionists who in his opinion have taken the sensible middle road between international modernism and Australian provincialism. Terry Smith, on the other hand, deplores the derivativeness of our art from an overseas avant-garde (specifically New York art) and reaches the pessimistic conclusion that “As the situation stands, the provincial artist cannot choose not to be provincial”. A distrust of the relentless progress of mainstream modernism becomes symptomatic of art in the seventies which witnessed the quite rapid collapse of the mainstream formalist ideology and its replacement by a plurality of styles and concerns.

Ironically perhaps, it is McCaughey who returns in 1980 to reflect upon the passing from popularity of formalist inspired styles in an aptly entitled article, ‘Surviving the Seventies in Australia’. Alongside references to “high, modern painting” and a sideswipe at the “70s myth of plurality”, McCaughey gives a lucid and reasoned account of the fate that befell painters whose styles he had previously championed in his criticism.

It is much easier to describe the pluralistic concerns of seventies art than to account for why this pluralism took place. Here I thought Gary Catalano’s article, ‘The Ancestry of “Anything Goes”: Australian Art Since 1968’ (Meanjin, vol. 35, no 4, 1976) was possibly worthy of inclusion in this anthology for, amongst other things, Catalano does suggest that the economic recession of the seventies may have fostered the growth of the more ephemeral, less tangible art forms such as body art and conceptual art. What was the point in producing precious objects when there was no market for them?

In her perceptive though somewhat meandering article, ‘Quattrocento Melbourne’, Margaret Plant draws attention to the fact that the variety of coexisting styles during the seventies was paralleled by reversals and contradictions within the work of individual artists. This deliberate disruption of style may reflect the influence of Marcel Duchamp, but Plant also suggests the possible effect of the large group exhibitions of contemporary art which came into prominence in Australia during this time.

These publicly promoted exhibitions invariably brought to Australia the work of important overseas artists to be shown alongside our local artists. The position of the provincial artist was thus enhanced through his easy assimilation into an international context. Yet these exhibitions also acted as decisive arbiters of the most recent style or trend. Faced with potential obsolescence, the artist must renew or redevelop the basis of his art to maintain his contemporary relevance.

It is interesting to trace in this anthology the writers’ differing attitudes towards the role of the individual artist in society. Daniel Thomas suspects that the best art has always been highly individual – and what art could be more individualistic than the nude body of Stelarc suspended in mid-air by a system of wires and hooks piercing his bare flesh?

Other writers demand an art that is socially responsible and one that rejects the high subjectivity and self-indulgence of the traditional avant-garde. Behind the political art, feminist art and art produced through the collaboration of individuals, lies an optimistic philosophy that the artist can function effectively with society and change it. Advocacy is a legitimate role for criticism and the times were perceived to demand advocacy for women’s art. Yet some writers perform the task with more subtlety and control than others, just as Janine Burke does compared with Ann Stephen in this anthology. In retrospect the apparently conflicting calls for individual subjectivity or a collective social responsibility now appear more closely related; they are linked by a desire for a sincere personal content in art and the struggle of the artist to establish a meaningful identity within his own society.

Paul Taylor’s article on ‘Australian “New Wave” and the “Second Degree”’, with its notes testifying to his reading of Umberto Eco and Roland Barthes, provides a fitting conclusion to this anthology, for it brings the seventies to a close and announces the beginnings of post-modernism. Taylor’s art world is not that of the naïve idealism of the seventies with its sincere believe in just causes, but is one where a person might be “just as willing to embrace a good pair of shoes as a good painting”. Real choice is an illusion within a highly developed capitalist society. One artistic image is open to an infinite variety of meanings, but there remains a nostalgic yearning for the time when signs spoke clearly for themselves. The seventies?

It is one thing to entitle a book Anything Goes, but it is quite another to make the name the basis of editorial policy. Apart from the fact that the proof reading appears to have been lax, one has to search through the minute print on page four to discover when and where these articles first appeared. The reader is thus denied immediate access to the original context of the criticism, potentially one of the most interesting aspects of this varied anthology.

Personally I find Taylor’s claim in the introduction that the “Seventies are too complex and varied, too present, to support a critical analysis of their outcome now” something of a cop-out. What the general reader needed was a lucid and informative introduction to some of the central issues rather than the self-congratulatory one that Taylor offers us. Still, this book is a very worthy enterprise, interesting to read and good for the cause of contemporary Australian art and criticism.

Comments powered by CComment