- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Neglected poet

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Thoroughly researched, well ordered, factual biography like Doherty’s Corner appeals to me. If, as is usual with a life-history, there is occasion for reading between the lines, I’m left alone to do it unhampered by authorial speculation. It often happens that when subjects of biographies live into the era of the writer of the book, facts emerge during research that might offend the feelings or sensibilities of still-living people. Burke has excluded anything of this order. In other words the book is very interesting and a model of usefulness and good taste.

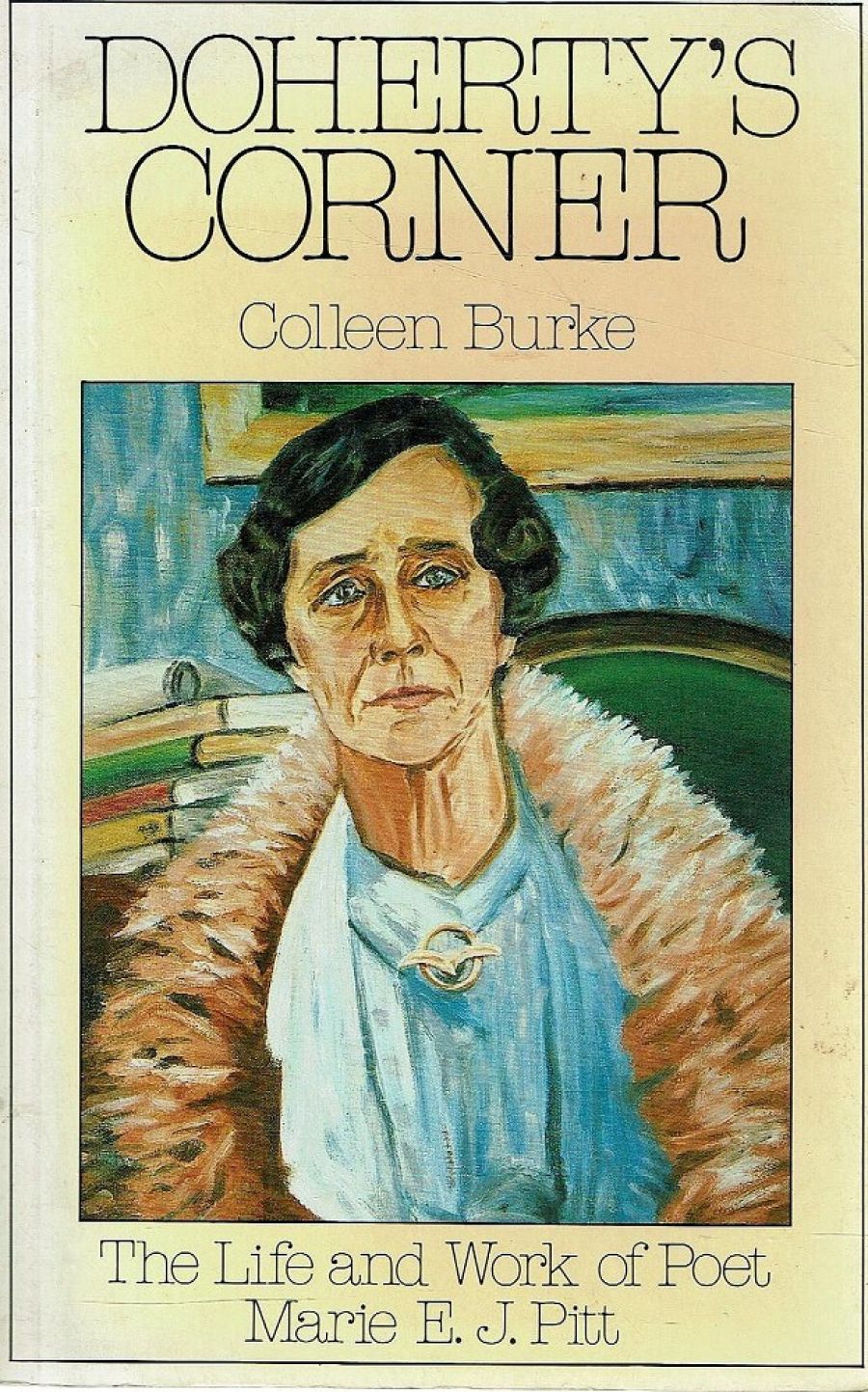

- Book 1 Title: Doherty’s Corner: the life and work of poet

- Book 1 Biblio: Angus and Robertson, 154pp., illus., index, $9.95

Burke offers an anthology of Pitt’s poetry at the end of the volume, and in the body of it generously quotes from some of her prose writings.

Who was Marie E.J. Pitt? Don’t trouble to consult the peculiar Oxford History of Australian Literature or its new companion, the Oxford Anthology of Australian Literature, which must be among the most useless reference volumes ever devised. H.M. Green includes Pitt with a reasonable .■summary in his History though her somewhat surprising late-life friend, the anarchist poet Harry Hooton, thought Green unfairly excluded her from another work saying: “He couldn’t classify you – you were too big to fit into his pigeonholes.” (However, from my youthful recollection of Hooton, I’d not pay too much heed to hint). You’ll find other brief references if you look far and wide enough, but Marie Pitt really does both merit and need this book.

Its illustrations show, for a start. that she was surely one of the most handsome women ever to adorn Australian Letters, with a slender body and features both spirited and spiritual. She was born to a pioneering farming family in Victoria in 1869. Her Catholic father, Edward McKeown was Irish. Her mother, Mary Stuart (nee Dawson) was Presbyterian Scots. In some ways the family history and talents parallel those of Shaw Neilson’s family. Of him Marie Pitt wrote:

Our stories, if gathered and compared, would I think have much in common. I always think of us at the stepchildren of Fortune in the Story of Australian Literature – the resemblance is curious and poignant.

There are obvious affinities between some of Neilson’s poems and some of Pitt’s, and Burke briefly discusses technical correspondences that might make an interesting study. That some of Marie Pitt’s poetry bears such high comparison indicates the quality of the best of her work.

She had a hard-working childhood and youth on the parental farm, and a fairly short and scrappy formal education at Wy Yung State School at Doherty’s Corner. There must have been books in the house, though they are not mentioned in detail, because her earliest writings quoted here employ a large and sophisticated vocabulary.

She married William Henry Pitt, a handsome farmer from Tasmania. Tasmania, where she lived during much of her married life, is the background for many of her poems. After a few years farming, Pitt obtained work in goldmines on the wild Tasmanian west coast. Four children were born – two girls and a boy lived. The Pitts were always struggling financially but were rich in companionship; Pitt encouraged Marie’s early writing of poetry, some of which was published in the Bulletin. They shared reformist political and social concerns.

Then Pitt contracted Pthisis – he was to die in his early forties. The family moved to Melbourne where he found unskilled labouring work with the Railway Department until he became too weak to continue so:

She turned her hand to writing for the press, casual clerical work, roll checking, doing anything to earn a living. She was also a census collector, and then a part-time reader for a publishing company.

She joined the Victorian Socialist Party and later edited its journal, the Socialist, for which she wrote a great deal. For above all she was a passionate reformer in word and deed and the greater part of Colleen Burke’s story tells of Marie Pitt’s commitment to both political and social reform.

For decades she was the “close companion” of the poet Bernard O’Dowd; although they were conventional people and distressed by their situation, after 1920 they lived together. In Melbourne too she was involved with literary groups and writing friends and she corresponded with others, including Mary Gilmore, who lived elsewhere. She was widely published. Her poem ‘Ave Australia’ won the ABC National Lyric Competition for a national anthem in 1945. She died in 1947.

Why then was Marie E.J. Pitt so nearly forgotten when Colleen Burke became interested in her story and her career? Bernard O’Dowd said:

She didn’t gel the hearing or criticism she was entitled to as a poet, that men and women her inferior are getting, because she criticised the press, the Church and the State.

Her friend W.F. Wannan Snr thought the political content of much of her writing might not be “appreciated and might be censored”. She, as a feminist, was very conscious of the difficulties experienced by a woman who was also family breadwinner and fond mother.

In fact, Marie Pitt did have considerable recognition (and a literary pension) and many good, and influential, friends in the writing world.

I suspect she became forgotten chiefly because she (and several other poets of her generation) were unlucky in that the techniques and concerns of Australian poetry changed so much and so rapidly in the 1940s. To my generation work like hers came very quickly to seem old-fashioned and unappealing. Much too quickly, though there were reasons for what happened. With the shame of hindsight I recall that, in about 1952, I read most of Marie Pitt’s published verse, chose a ballad called *A Bush Legend’ for Australian Bush Ballads, and gave her work no further thought.

In any era 1 think it is important to distinguish between what seems trendy rubbish from the recent past; what becomes temporarily old-fashioned, and what eventually is perceived to embody the force and spirit of its time. (This is a process that affects almost everything from fashions in buildings and dress, to all the arts.) Down the perspective of time Pitt’s life and works now appear to be ripe and ready for rediscovery and Colleen Burke provides a splendid introduction.

Footnote

Burke discusses a somewhat mysterious poem called ‘The Recantation’ which was undoubtedly written by Pitt, though she disowned it for a long time. It was first published in the Socialist and signed ‘Joseph Merizeiue’. The pseudonum suggests to me that Pitt was an early user of ‘Strine’. Leave aside the name ‘Joseph’ – the surname could be spoken as ‘Me’r [or] is ‘e I/you, eh?’

Comments powered by CComment