- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Custom Article Title: Susan Sheridan reviews 'New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham' edited by Nathanael O’Reilly

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This manifesto for free verse comes from a poet whose associates at the time included Harold Monro, Richard Aldington, and D.H. Lawrence in London, Harriet Monroe and Louis Untermeyer in New York, Natalie Clifford Barney in Paris. Anna Wickham (1883–1947) mixed with the modernist writers and artists of her time on both sides of the Atlantic and was widely admired for her early books, The Contemplative Quarry (1915), The Man with a Hammer (1916), and The Little Old House (1921).

- Book 1 Title: New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing $29.99 pb, 171 pp, 9781742589206

Wickham was a modernist poet who wrote mostly in conventional verse forms, and whose imagery is as often fin de siècle as it is modernist. She was a mass of contradictions, which are reflected in her poetry: a free thinker who remained deeply marked by her Catholic education, a woman artist torn between the exemplars of her rationalist father and spiritualist mother. She was a feminist in thrall to the idea of heroic motherhood of sons, a passionate woman capable of infatuations with women as well as men, who stayed married to her husband (a London solicitor and amateur astronomer), though she hated his chilly demeanour and his upper-middle- class manners.

She belonged to that remarkable generation of literary women, modernists in life if not always in poetic technique, who were social and political radicals, supporting the women’s suffrage movement and various experiments in free love and communitarian living. They had much in common with the women of second-wave feminism, who often included Wickham in their anthologies of women’s poetry. In 1984, Virago brought out a selection of her poetry and prose, edited by R.D. Smith, to mark the centenary of her birth. Susan Hampton and Kate Llewellyn, editors of the Penguin Book of Australian Women Poets (1986), considered Wickham one of the historical poets who was ‘closest in mood and subject matter to contemporary poets who form the bulk of the anthology’.

Wickham appears in various Australian anthologies because she had a significant Australian connection: the only child of restlessly emigrant English parents, she grew up in Queensland and Sydney in the 1890s, returning with them to Europe at the age of twenty. Hence her appearance among the historical poets in UWAP’s series (along with Lesbia Harford, John Shaw Neilson, Dorothy Hewett, and Francis Webb).

This edition of her work, New and Selected Poems, edited and introduced by Nathanael O’Reilly, includes 100 previously published poems and 150 more chosen from the more than one thousand unpublished poems that exist in manuscript. Frustratingly, given the massive task he has undertaken of reading and selecting from the British Library manuscript collection, the editor offers no commentary on the principles which guided his decisions. There is only the briefest of introductions, sketching the circumstances of Wickham’s life, and a note on his editorial decisions (mainly involving restoring the poet’s original punctuation in the poems previously published in the Virago edition). There is no mention of the manuscript collection held in Paris, which appears to contain yet more unpublished poems, mostly included in love letters to Natalie Clifford Barney. Perhaps there is an important distinction to be made between poems Wickham chose to publish and those she intended to remain private.

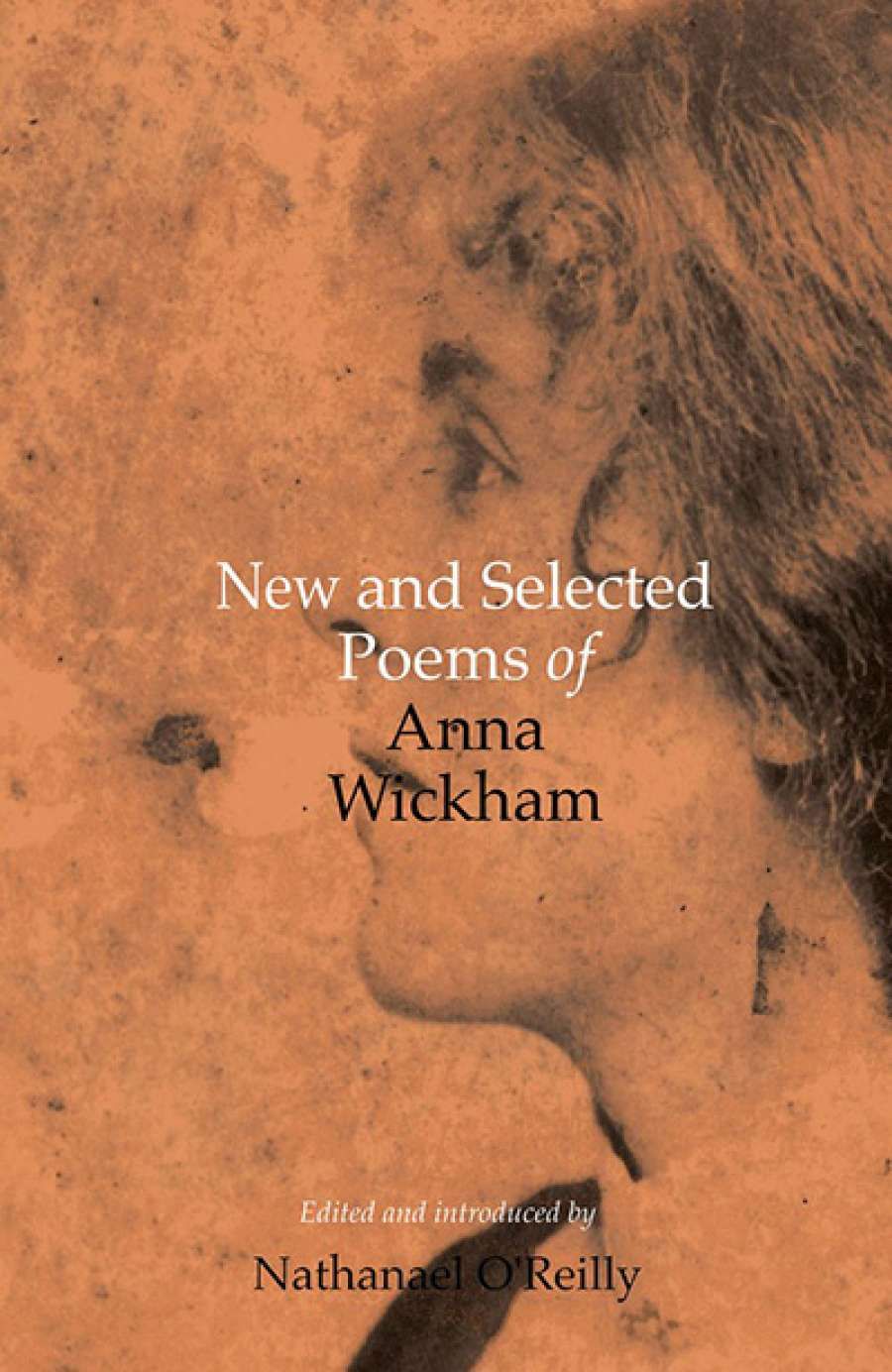

Anna Wickham (Wikimedia Commons)

Anna Wickham (Wikimedia Commons)

Since the 1980s there has been a significant feminist rescue operation aimed at extending the borders of modernist literature to include work, like Wickham’s, that is formally conventional but expresses radical views, especially attacks on patriarchal restrictions on women. This is presumably the context which allows O’Reilly to claim Wickham as ‘one of the most important female poets’ of the first half of the twentieth century and ‘a pioneer of modernist poetry’. But without any elaboration of that context of feminist literary studies of modernism, such claims seem overblown. Wickham’s poetry is fierce and crude and often comic; it has little in common with the feminist modernism of, say, HD or Mina Loy.

Just as Wickham’s attitude to ‘private’ or ‘public’ poetry is unknown, so too we know little about how she regarded herself as a poet. She once retorted to a gallery owner, who objected to her loud expressions of dislike: ‘I may be a minor poet but I’m a major woman!’ The woman who canvassed support for a manifesto titled The League for the Protection of the Imagination of Women with the slogan World’s management by entertainment is unlikely to have taken herself too seriously as a public figure. She appears to have been larger than life – a physically imposing woman, and a self-mythologiser.

It is no simple matter to estimate her importance to women’s writing, or to twentieth-century poetry more generally, but it is good to have this generous collection of her work, which can be complemented by recent biographical and critical studies.

Comments powered by CComment