- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is a critical truism, if not a cliché, that poetry estranges: it makes things strange, so that we can see the world and ourselves afresh. Defamiliarisation, the uncanny, even metaphor, are all fundamental to poetry’s estranging power. Unsurprisingly, madness, vision and love have also long been poetry’s intimates, each involving the radical reformation – or deformation – of ‘normal’ ways of seeing the world. One might describe poetry as surprisingly antisocial, since poets have from ancient times been associated with social isolation, distance or elevation, as well as with madness.

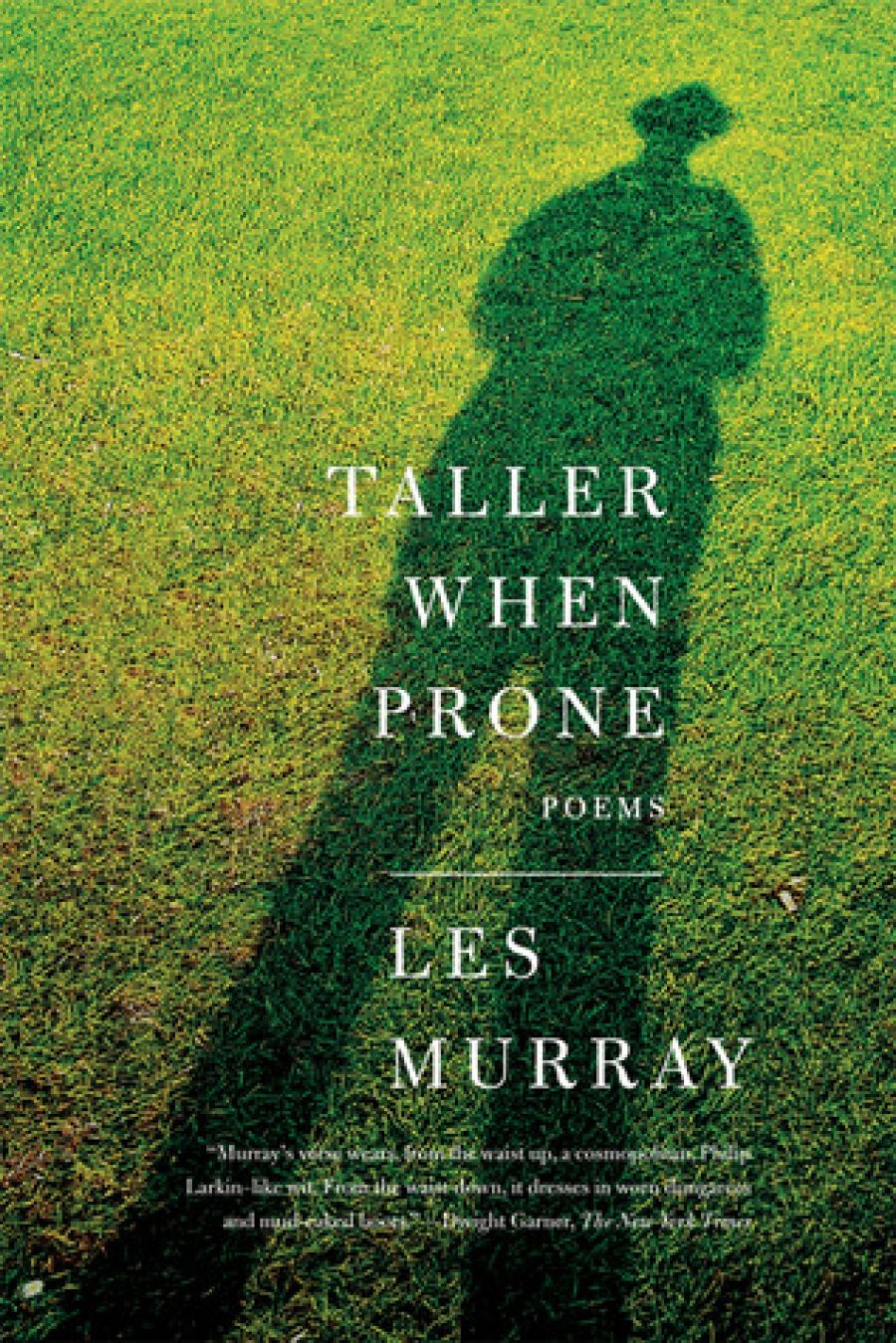

- Book 1 Title: Taller When Prone

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $24.95 pb, 96 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/QVeyx

Poetry, then, offers competing urges: the move towards singular, estranging vision and the move towards sociability. This tension is relevant when considering Les Murray’s poetry. Murray is often described as Australia’s unofficial poet laureate or the ‘Bard of Bunyah’, after the rural town where he grew up and has lived for the last twenty-five years. But parallel to this element in Murray’s career is an estranging one. Murray has been involved in various cultural controversies, and critics have sometimes deplored the antagonistic nature of his work. Interestingly, Murray’s most divisive and controversial collection, Subhuman Redneck Poems (1996), was also his most profoundly communal work, speaking, as the ironic title indicates, for the rural poor.

If his last few collections are anything to go by, Murray – now in his seventies – has mellowed somewhat. Controversy is absent, and his poetry is less interested in the social divisions of Australian history, Murray’s autobiography or contemporary politics. One overwhelmingly persistent element of estrangement in his work, though, is its stylistic idiosyncrasy. Despite being characterised as ‘popular’, Murray’s poetry is surprisingly difficult. This is not, though, because of obscurity. Murray’s poems reveal rather than conceal, though considerable work is required to allow the revelation to occur.

And why not? Murray’s profound idiosyncrasy is his major source of power. He is an original, and his originality is not – as some detractors may prefer – often in the service of ideology, negativity or special pleading. The poems in this latest collection, Taller When Prone, are frequently – as Murray generally is – funny, witty, and light, which is not the same as inconsequential. A very few poems are inconsequential, though not light. For the most part, however, Murray’s humour is part of a complex whole, as ‘Nursing Home’ suggests, which opens with mordant comedy (old age is the ‘the end of gender, / never a happy ender’), and ends somewhere near sentimentality.

Many poems begin sounding resolutely odd. ‘The Death of Isaac Nathan, 1864’, for instance, begins: ‘Stone statues of ancient waves / tongue like dingoes on shore / in time with wave-glitter on the harbour / but the shake-a-leg chants of the Eora // are rarely heard there any more / and the white man who drew their nasals / as footprints on five-lined paper / lies flat away up Pitt Street, // lies askew on gravel Pitt Street.’ But, as the poem shows, Australian colonial history – an abiding interest of Murray’s – is inherently odd. The eponymous Nathan, an Anglo-Australian composer, was the first to transcribe the music of indigenous Australians (the Eora of Murray’s lines), and he was the son, as the poem later tells us, of a Polish refugee who believed himself to be the son of the last king of Poland. The puzzling nature of the poem’s opening forces the reader to deal with strangeness because the poem itself is dealing with strangeness (of the past, of others, of everyday life).

Murray deals with the strangeness of things like no one else. Of a corpse he writes: ‘After three months, he could only / generalise, and had started smiling’ (‘The Suspect Corpse’). While poetic defamiliarisation is often associated with outlandish comparisons and imagery (think of Craig Raine), Murray can defamiliarise with the lightest of touches. In ‘From a Tourist’s Journal’, we have this particular tourist’s vision of India: ‘We came to Agra over honking roads / being built under us, past baby wheat / and undoomed beasts and walking people.’ Here the adjectives, those much-maligned modifiers, do all the estranging work with little fanfare. (The neologistic ‘undoomed’ is the only hint of the outré).

While Murray’s style is an estranging one, in as much as it is ‘difficult’ or ‘idiosyncratic’, his interests are far from those of an isolate. For Murray, the world is endlessly fascinating, and his inward, estranging originality is usually directed outwards to the social world. To say that ‘Medallion’ is about a walnut, or that ‘Eucalypts in Exile’ is about trees, is ridiculously insufficient. Poems such as these seek the marvellous in the most ordinary of things.

This is not an original project. The surrealists, in their different ways, attempted the same thing. Rather, it is the execution that makes Murray’s poetry so worthy of attention. This is seen, for instance, in his description in ‘Lunar Eclipse’ of ‘the ocean cliffs / stacked high as a British address’. Anyone who has sent a letter to the United Kingdom may have noted the size of British addresses, but Murray is surely the first to put that observation to (brilliant) poetic use.

Murray’s eye is not merely for the physical. He is adept at noting social differences, as in his description of ‘Visiting Geneva’: ‘I rolled in on a Sunday / to that jewelled circling city / and everything was closed / in the old-fashioned way.’ Murray also has a love of the plurality of ‘real life’, as seen in ‘The Conversations’, with its lists of extraordinary ‘facts’, one of which – ‘The glass King of France feared he’d shatter’ – refers to Charles VI, who suffered from the ‘Glass Delusion’.

Murray’s encyclopedic mode is especially engaged, as we might expect, by language. The list of definitions in ‘Infinite Anthology’ is humorous evidence of this (though, I’m not sure about the accuracy of Murray’s definition of ‘bunny boiler’). I particularly liked the definition of ‘dandruff acting’: ‘the stiffest kind of Thespian art.’

At times Murray’s broad interests bring together the ancient and the topical, as in ‘Hesiod on Bushfire’. The topicality of the poem, written in the shadow of Black Saturday, makes its Hesiodic advice especially pointed: ‘Never build on a summit or a gully top: / fire’s an uphill racer deliriously welcomed / by growth it cures of growth. / Shun a ridgeline, window puncher at a thousand degrees.’ Later, Murray points out the unexpected fact that ‘Grazing beasts are cool Fire / backburning paddocks to the door’. ‘Hesiod on Bushfire’ is one of the collection’s standout poems (all of Murray’s collections have a handful), as seen in its startling imagery: ‘The British Isles and giant fig trees are Water. / Horse-penis helicopters are watery TV.’ The complex adjective ‘horse-penis’ is all the more striking when we consider how accurate it is with respect to those firebombing helicopters we watch on television during bushfires.

Taller When Prone shows that the contrast between poetry as estranging or uniting is ultimately untenable. ‘Phone Canvass’ illustrates this. The poem narrates the poet chatting with a caller from the Blind Society, ‘the donation part’ over, who is answering his ‘shy questions’. The reported speech brilliantly describes, in poetic terms that could only be called defamiliarising, what it is like to walk a city street if one is blind. In a mere nine lines, Murray unites estranging ‘vision’ (solicited from someone without sight) with the profound sociability of one person simply talking with another. ‘I can hear you smiling’, says the caller, artfully bringing together synesthesia and social interaction.

Comments powered by CComment