- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

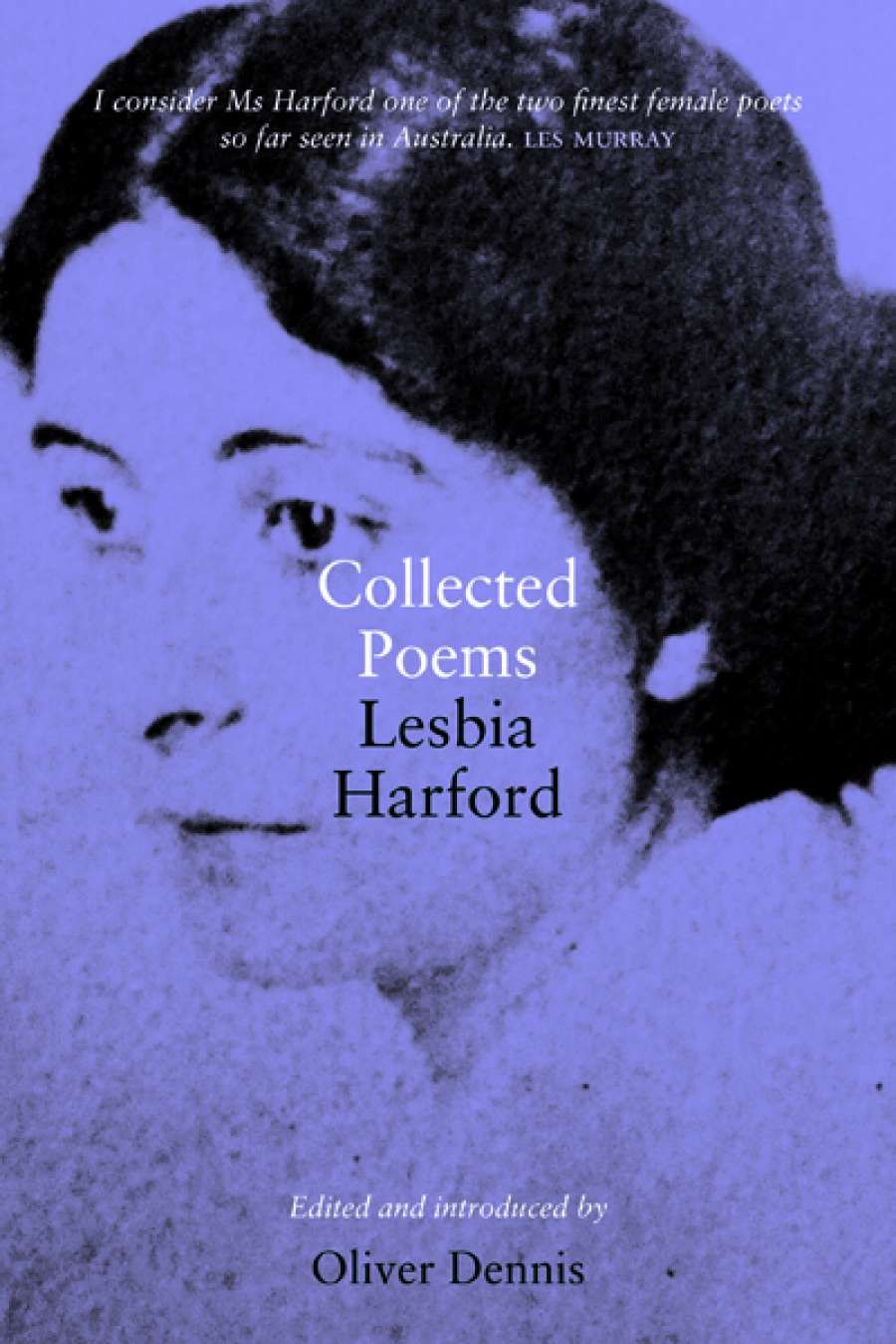

- Custom Article Title: Susan Sheridan reviews 'Collected Poems: Lesbia Harford' edited by Oliver Dennis

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The slender, wiry lyrics of Lesbia Harford

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In her short life (1891–1927), Lesbia Harford wrote hundreds of poems and a novel, took a law degree at the University of Melbourne, had love affairs with both women and men, worked as a machinist in clothing factories, and was active in the anti-conscription movement during World War I and the International Workers of the World (‘the Wobblies’). She was the quintessential modern woman of the early twentieth century.

- Book 1 Title: Collected Poems

- Book 1 Subtitle: Lesbia Harford

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $29.99 pb, 136 pp

Her poetry, above all, is what she is remembered for today – slender, wiry lyrics that are simple, often colloquial, in diction, and rhythmically complex. Here is ‘Deliverance through Art’:

When I am making poetry I’m good

And happy then.

I live in a deep world of angelhood

Afar from men.

And all the great and bright and fiery troop

Kiss me agen

With love. Deathless Ideas! I have no need

Of girls’ lips then.

Goodness and happiness and poetry,

I put them by.

I will not rush with great wings gloriously

Against the sky

While poor men sit in holes,unbeautiful,

Unsouled, and die.

Better let misery and pettiness

Make me their sty.

In this poem of late 1915, the renunciation of poetry ‘while poor men sit in holes’ is a gesture that simultaneously celebrates its celestial realm and demands that it also speak to wartime misery. It is, in the words of critic Ann Vickery, ‘ethically and politically charged’ poetry.

Lesbia Harford’s connection to Sappho is not just a question of her need of ‘girls’ lips’ (or her first name). Her use of the short lyric to give the impression of natural speech recalls Sappho, and in fact her stanza forms are often reminiscent of Sapphics – that is, quatrains where the final line is short and dramatic. These ‘docked’ lines occur in other stanza forms that she uses, as in the poem quoted.

Her poems celebrate love and the pain of love, even its destructiveness. When her man tells her she is so light she must have hollow legs, she retorts:

‘Yes

I’ve hollow legs and a hollow soul and body.

there’s nothing left of me

you’ve burned me dry.’

(‘Grotesque’)

but also, from ‘I must be dreaming through the days’:

So much in life remains unsung,

And so much more than love is sweet.

I’d like a song of kitchen maids

With steady fingers and swift feet.

So she sings of the working girls who are her daily companions, with whom she shares the pleasure of looking at ‘Cherry plum blossom in an old tin jug’. As she wearily looks across at her workmate Moira, who has a red tape measure, it reminds her of blood, or a fire quickening: ‘It’s Revolution. Ohé, I take pleasure / In Moira’s red tape measure’ (‘To look across at Moira gives me pleasure’). And, unusually, she writes of menstruation:

We have our hours

Of dark, interlunar dream

Whence we emerge with bodies that shine and gleam

Like newborn flowers.

(‘Periodicity [1]’)

Harford’s closest poetic peers in Australia would be Mary Gilmore and John Shaw Neilson, company that Les Murray creates for her in his anthology Hell and After: Four Early English-language Poets of Australia (2005). But unlike those two older poets, Harford did not seek publication for her poetry: a small selection appeared in a magazine in 1921, but the rest stayed unpublished, though she would show them to friends like Nettie Palmer (who would publish a selection of seventy-eight of Harford’s poems in 1941) and Katie Lush, her philosophy tutor and the object of her strongest Sapphic passion. ‘Mortal Poems’ seems to explain this lack of interest in going public:

I think each year should bring

Little fresh songs

Like flowers in spring

That they might deck the hours

For a brief while

And die like flowers.

Harford did, however, try and fail to have her novel, The Invaluable Mystery, published. After her death it was lost for sixty years, and finally published in 1987. Its discoverers and editors, Richard Nile and Robert Darby, describe it as showing ‘something of the truth of the home-front from the point of view of women, the misfits who were interned and the dissidents who were gaoled’. At the war’s centenary, it is as well to recall the extent of dissent during World War I and the ‘ferocity of the government’s determination to stamp it out’. For example, Lesbia’s lover, Guido Baracchi, was convicted of ‘making statements likely to prejudice recruiting’ and ‘attempting to cause disaffection among the civil population’; he went to jail for three months rather than pay the fine imposed.

The publication of her novel marked one of several rediscoveries of Harford: in 1985 Marjorie Pizer published an edition of her poems, with a long biographical essay by Drusilla Modjeska. Harford has been a significant presence in Australian feminist thinking about women’s writing ever since. Debra Adelaide’s 1987 collection of essays on colonial writers takes its angelic title, A Bright and Fiery Troop, from the poem ‘Deliverance through art’. Harford’s work has been the subject of excellent critical essays by Jennifer Strauss, Ann Vickery, and Jeff Sparrow. (There is an up-to-date list of secondary works about Harford in her Wikipedia entry.) The biennial Lesbia Harford Oration, inaugurated in 1999 by the Victorian Women Lawyers’ Association, honours women’s political activism.

The volume under review, the latest attempt to make her poetry available, offers a generous selection of the poems accompanied by a foreword from Les Murray, who praises her as ‘one of the two finest female poets so far seen in Australia; the other has to be Judith Wright’. Oliver Dennis’s brief introduction draws attention to formal features of her poetry, though it misleads in claiming that its distinctiveness lies in its ‘pure, incidental song’, a claim which neglects the passionate commitments that drive it.

Dennis publishes ‘just over half of the 400 poems existing in manuscript’, of which he reckons a third have not been published previously. They are arranged chronologically, but without any dates, yet it appears from the Modjeska and Pizer edition that Harford was in the habit of noting precise dates, and these, of course, enable reading the poems in relation to their biographical and historical contexts, and also tracing developments in her art. Readers can access that earlier edition, which also supplements this rather skimpy account of her life, and also the Nettie Palmer edition of 1941, at www.poetrylibrary.edu.au/poets/harford-lesbia.

Comments powered by CComment