- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Custom Article Title: Anthony Lynch reviews 'Travelling Without Gods: A Chris Wallace-Crabbe companion' edited by Cassandra Atherton and 'My Feet Are Hungry' by Chris Wallace-Crabbe

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Tributes to Chris Wallace-Crabbe

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

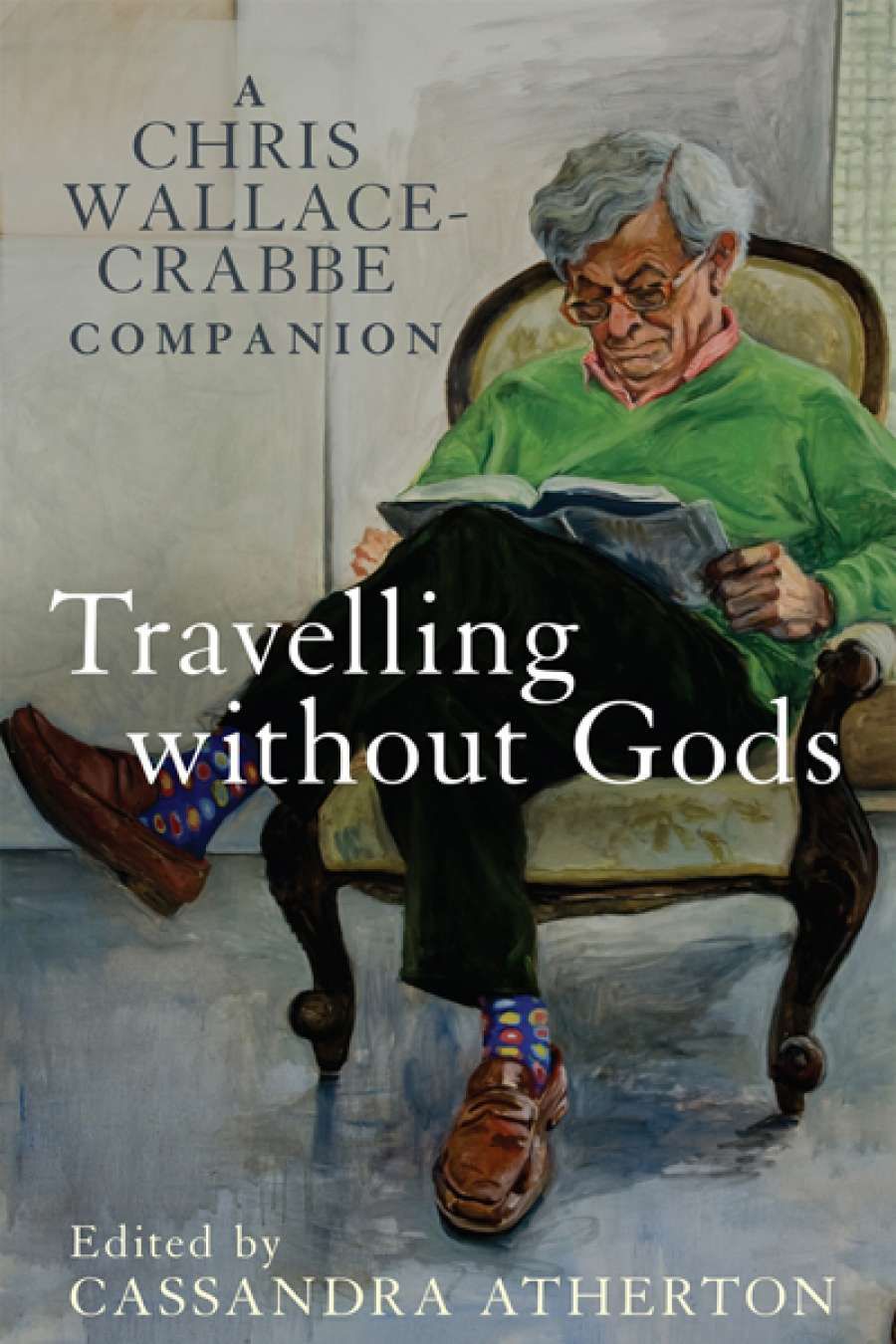

The title of Cassandra Atherton’s anthology, Travelling Without Gods, alludes to the particular brand of agnosticism that has run through Chris Wallace-Crabbe’s work over many decades. Journeying sans deity is evidenced strongly in the poet’s latest collection, a book which, like Atherton’s, has been published to coincide with Wallace-Crabbe’s eightieth birthday.

For a non-believer, Wallace-Crabbe’s My Feet Are Hungry makes frequent reference to Christian ideology. This is in marked contrast to a number of Australian poets – Judith Beveridge, Barry Hill, Robert Gray among them – whose work in recent years testifies to the influence of Buddhism. Wallace-Crabbe’s Christian saviour is located firmly in the historical rather than the sacred. Only mildly irreverent, the poet shows respect for a figure who sides with the disadvantaged in an era of raging commercial interest and power-mad politicians: ‘Did Roman nails deserve his blood? / Even for someone who venerates money / Here is a story of absolute good’ (‘And the Cross’).

- Book 1 Title: Travelling Without Gods

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Chris Wallace-Crabbe companion

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $39.99 pb, 236 pp

- Book 2 Title: My Feet Are Hungry

- Book 2 Biblio: Pitt Street Poetry, $25 pb, 94 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): /images/October_2014/my%20feet%20are%20hungry%20-%20colour.jpg

‘And the Cross’ offers a précised life of Christ – ‘a tale you’ve all heard bits of’ – told with the ironic distance of the non-believer. Similarly, ‘Following Me, Old Footprints’ ponders: ‘For what, I ask you, was somebody called our saviour / in the turbulent middle east ... // two long Ks, ago?’ The soul also gets a working over. The opening of ‘The Only’ asks ‘Where sleeps the soul?’ Wisely more inclined to question than to offer definitive answers, Wallace-Crabbe suggests ‘a living soul may be no more than / rhetorical habits from another age’. ‘Our Place and Time’ sees the poet question ‘where soul might have its home’.

The soul is an emblem of consciousness – ‘travelling with my body // in a fragmentary corner of space / tucked away across the billion universes’ (‘The Only’). Wallace-Crabbe locates himself among the minutiae comprising multiple universes, but also, more locally, as the product of European and Australian cultures. My Feet Are Hungry sees him invoke a wide range of (high) cultural references, with a large cast assembling in ‘Chianti’ that includes Stendhal, Byron, Keats, Henry James, the Brownings, ‘lofty-minded Ruskin’, and Rousseau. Fond of nodding to the literary canon while earthing its hall of fame brigade, Wallace-Crabbe tells us Stendhal is fat, James a ‘tubby figure’, Ruskin a mother’s boy, and that Rousseau ‘wanders, wanks and weeps’. As in so much of Wallace-Crabbe’s work, an older Australian vernacular is readily brought to bear: ‘willy-nilly’, ‘buggered-up’, ‘pisses off’, ‘the whole caboodle’, ‘electronic doo-dads’ – aptly, this last in a poem (‘Hours’) dedicated to a leading practitioner of that vernacular, Alan Wearne. As many of these poems reveal, and as essays in Atherton’s ‘companion’ demonstrate, Wallace-Crabbe brings an antipodean sensibility to the Occidental world, though the claim of ‘being / a son of dry gumleaves and gravel’ (‘Snowfall’) seems forced from one with such strong bonds to a university milieu and to a particular inner-urban strip of Melbourne.

‘Nor Am I Out of It’ begins with a delicate reflection on pottering, which for Wallace-Crabbe means not only fiddling around in the backyard, but a meta-physical musing on our position within, and perception of, the world, and the inability of language to describe it. Struggles to apprehend are often conveyed with rhetorical questions. In Atherton’s book, Paul Kane makes an interesting argument for Wallace-Crabbe, in an Emersonian tradition, unsettling us, his readers, and that ‘just when we think we’ve got his measure, it turns out he is measuring us. We’re left holding the metaphysical bag while he walks away to the next poem.’ Kane points out that we are nonetheless left with ‘a genuine drive to inquire after ultimate – or frequently penultimate – questions’. Nevertheless, one might sometimes wish Wallace-Crabbe hadn’t walked away to the next poem so readily; that whimsy might have yielded further to meditative mood and imagery.

Chris Wallace-Crabbe

Chris Wallace-Crabbe

My Feet Are Hungry comes close on the heels of last year’s New and Selected Poems, in which many new poems explored mortality with great poignancy. The new collection continues the theme. ‘Flowing’ is a short and beautiful poem about the passing of an unnamed poet. ‘Alas’ recalls hearing of Seamus Heaney’s death. Along with Heaney, the two Peters, Porter and Steele, are among close poet friends Wallace-Crabbe has lost in recent times. Another Wallace-Crabbe domain, the domestic, is in strong evidence, and renovations to the speaker’s house provide an appealing structure to some poems. As in ‘Remnants’, the domestic is often set skilfully against darker, larger world events. And Wallace-Crabbe’s usual attention to form, employing and discarding as he sees fit the quatrain or rhyme, is put to effortless effect. ‘The Flowering Meadow’, a free-flowing translation in tercets of Canto XXVIII of Dante’s Purgatorio, fittingly comprises the final section of the book, placing us back in a liminal zone of biblical backyard.

Paul Kane’s is one of the finest contributions to an impressive line-up artfully assembled by Atherton in Travelling Without Gods. Inside the cover, featuring a superb portrait by the poet’s partner Kristin Headlam, are essays exploring the sweep of Wallace-Crabbe’s work, ‘readings’ of major poems, memoirs, poems written in recognition of the poet, and extracts from Wallace-Crabbe’s handwritten journals. As Atherton warns in her introduction, ‘if you are Chris’s friend or have been his colleague, you will be in his journals somewhere ... very occasionally you might not like what you read’.

There is little chance Wallace-Crabbe will not like what he reads in this companion compiled ‘in the tradition of Chris’s journals’ with ‘edgy juxtapositions’. Some might want more edge, and the laudatory tone risks making the book a kind of pre-digital Facebook post we can all ‘Like’. But Atherton’s assemblage works. Excellent poems intersperse the longer prose pieces – David Malouf, Lisa Gorton, Peter Rose, David McCooey, Andrew Motion, and Judith Bishop are among the poets, and Seamus Heaney closes proceedings with his ‘A Section’. As Atherton says, this poem – referenced by Wallace-Crabbe himself in his poem ‘Alas’ – may well have been Heaney’s last. With contributors well acquainted with Wallace-Crabbe personally, many of the essays intersperse memoir with analysis. Highlights include Kevin Hart’s discussion of Wallace-Crabbe’s longer sonnet sequences, Lyn McCredden’s tracings of ‘ontological uncertainty’ and the sacred and secular in the poet’s work, Paul Kane’s aforementioned essay, in which he discusses how for Wallace-Crabbe ‘the miraculous is grounded in the world’, and Patrick McCaughey’s portrait of the poet among painters.

Among memoirs, the poet’s brother, Robin, writes a funny, self-deprecating portrait of growing up together in South Yarra and East Ivanhoe, and Kate Darian-Smith relives Wallace-Crabbe’s long association with the University of Melbourne, recollections that might induce nostalgia for a time when managerialism had less hold over academia. Elsewhere, the repeated reminiscences of poetry clan meetings on Lygon Street might strike some as clubby, and the predominantly male assemblages of poetry influences and associates evoke the old modernist conceit that genius and greatness are male domains. That said, as Darian-Smith points out, Wallace-Crabbe has been a generous mentor to many young female writers.

In the pithy, short poem ‘Diptych’, Wallace-Crabbe offers two views: one decoratively with god, one ‘a giant overarching blankness’ without. If Wallace-Crabbe travels with any kind of gods, they are of the small ‘g’ variety. He has wavered little from the road he set out on decades ago. Let’s hope he pounds out many more miles.

Comments powered by CComment