- Free Article: Yes

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What makes a story compelling? When I was an undergraduate student at Deakin University, I was fortunate enough to be instructed in fiction writing by Gerald Murnane. His key criterion for the worth of a story was its capacity to mark his memory with an enduring image. Over time he used to cull books from his shelves that failed to impress him in this way.

Gerald’s anecdote, in a satisfying mise en abyme, has passed its own test. After twenty years I still imagine him inspecting an old paperback, his memory going over the book like a Geiger counter assessing a piece of potentially radioactive earth. That said, one might adopt different criteria for determining the value of a short story. There is a memorable voice – Annie Proulx’s American West short stories are like no other in that regard. There is plot or character – who could forget Gregor Samsa’s metamorphosis into a beetle?There is an innovative use of language or form – Ryan O’Neill’s ‘Figures in a Marriage’ tells the story of a relationship breakdown via graphs and charts. I am often struck by something perhaps less tangible but no less powerful: mood.

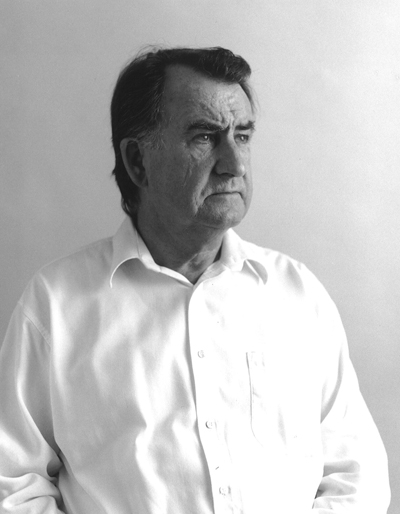

Gerald Murnane (photograph by Ian Hill)

Gerald Murnane (photograph by Ian Hill)

Literature is a moodful experience. This is perhaps most obvious in poetry, particularly of the Romantic kind, which is typically attuned to the ‘felt’ dimensions of language apparent in its rhythms, sounds, textures, and rhymes. Poetry, as the common complaint of students goes, is not always about conveying a ‘rational’ sense of things. Indeed, poetry often addresses experiences of emotional intensity that are difficult to cognitively process and articulate, such as love, pain, desire, or grief. The poet ‘feels’ his or her way into things, as does the reader.

However, feeling is important to fiction too. When I write fiction I do not ‘know’ what I am writing about, and as a reader of fiction I respond to moodful elements of stories that cannot necessarily be ‘understood’. The Metamorphosis, for instance, arouses feelings of disgust and confusion that are unforgettable. There is the humid and cruel mood of Flannery O’Connor’s short stories, memorably set in the American South – and setting, of course, is another factor that can render a work striking. Just thinking of Stanislaw Lem’s absurdist short stories makes me laugh. My favourite is ‘The Seventh Voyage’ of The Star Diaries, in which our astronaut encounters various doubles of himself, generated by time warps, and tries to win their cooperation to fix his damaged spacecraft. The story is a proud farce, and it evokes in me a sense of rebellious glee. Thinking of my experience judging short-story competitions, it is a common misconception that the mood engendered by a story needs to be sombre or agonised.

Feelings are often viewed with suspicion (which is itself another influential feeling). Indeed, emotions are sometimes seen as the narcissistic source of bad writing. Certainly, I do not believe that good writing is simply about self-expression. It might be the case, however, that good writing is a hard-won expression of idea and feeling combined – something that the short stories of Jorge Luis Borges, simultaneously intellectual and lush, beautifully illustrate.

In fact, separating ideas from feelings is becoming more difficult. Despite an enduring tradition of conceptualising emotions as forces that muddy thought – and art – this has undergone a re-evaluation in recent times. The role of emotion in the arts has also been revalidated. Antonio Damasio, who heads the Brain and Creativity Institute at the University of Southern California, is a leader in the kind of neuroscientific research that has shifted our view of the mind from some kind of cogitating machine to an embodied organ primordially responsive to feeling. For Damasio, feeling is actually inseparable from cognition. Feeling is also what provokes human beings to engage in the creation of art. Poetically evoking a potential feeling-rich scene of creativity, he argues in Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain (2010):

No set of conscious images of any kind and on any topic ever fails to be accompanied by an obedient choir of emotions and consequent feelings. As I am looking at the Pacific Ocean dressed in its morning suit, protected by a soft, gray sky, I am not just seeing, I am also emoting to this majestic beauty and feeling a whole array of physiological changes that translate, now that you ask, into a quiet state of well-being.

If literature is moodful, it is in response to the moodful experience of being alive. Indeed, quietude, of the kind Damasio experiences upon observing the dawn, is an emotion that might provide the compelling ‘feeling’ of a short story – one that a reader might remember many dawns later.

Comments powered by CComment