- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The 2012 centenary of the dramatic Scott–Amundsen race to reach the South Pole prompted several new non-fiction books on Antarctica. No fewer than five of them were reviewed in the December–January edition of London’s Literary Review, a welcome reminder of the superb Ferocious Summer (Profile Books, 2007) by Australian author Meredith Hooper, which won the Victorian Premier’s Award for Non-Fiction in 2008 (disclosure: I was convenor of that panel).

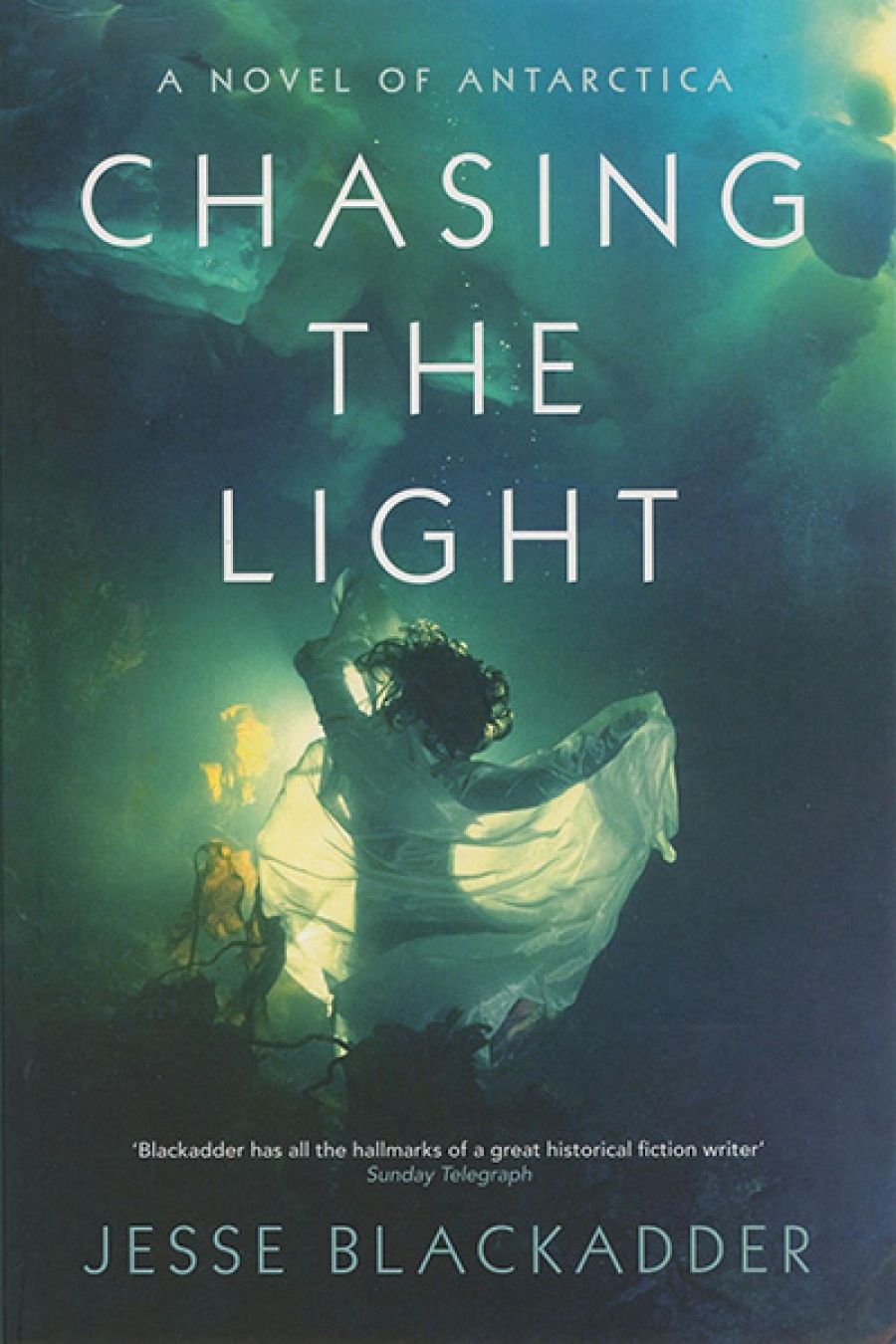

- Book 1 Title: Chasing the Light: A Novel of Antarctica

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $29.99 pb, 431 pp, 9780732296049

Now comes a fictional account, set roughly twenty years later, also by an Australian – writer and journalist Jesse Blackadder – of a race with a similar yet crucially different goal. This story hangs on the question of who will be the first woman to set foot in Antarctica. Nationalism and feminism are both at stake, but they pale in the glare of the personal jealousies and contentions that Blackadder injects into her plot. Ingrid Christensen, wife of the supremo of Norway’s fleet of whaling ships, yearns to be that woman, and her husband Lars has the power to make it possible. He agrees to take her south, aware that gratifying Ingrid’s desire will also enhance his country’s reputation. But Ingrid’s delight, it seems, may be subverted by the determination of another woman (sexy, spoilt, strong-willed Lillemor) who uses trickery to get herself onto Thorhavn and secretly plans to forestall the planting of any feminine boot but her own on Antarctica’s icy shore. A third woman, recently widowed and reluctant to leave her children, is unwillingly drafted as Ingrid’s companion. Initially, Mathilde’s lack of interest in whose foot lands first is perfectly genuine, but how long will she remain boxed in by private grief?

If this emotionally charged setup is beginning to seem rather novelistic, we recall that Chasing the Light is classified as a novel. But it all really happened, didn’t it? Well, not quite. An author’s note tells us that ‘the characters, though prompted by real people, are imaginary’. Yet the women, and some others, bear their real-life names. An afterword explains further that this ‘work of fiction’ is ‘inspired by the travels of Ingrid and Lars Christensen’ (who actually made four voyages together) ‘and of Ingrid’s female companions, Mathilde Wegger and Lillemor Rachlew’, but stresses that there was no evidence of competitive spirit among them. Thus the main events – the voyage via Cape Town and the climactic landing in Antarctica – are basedonreality, while the rivalry that sets Ingrid against Lillemor, the jealousy between Ingrid and Mathilde, and the constantly shifting loyalties played out among all three women, are a confection. But we only learn this after we have become thoroughly immersed in the human complexities. There is a sense of let-down ensuing from Blackadder’s afterword honesty that one does not feel with, say, Wolf Hall or Bring up the Bodies. Why?

Hilary Mantel, discussing her two Cromwell novels, argued: ‘I am not claiming authority for my version. I am making the reader a proposal.’ We accept these proposals not as absolute fact but as illustrations of Mantel’s famously meticulous research and brilliant insight into human behaviour. They are eminently probable. And there are many aspects of Chasing the Light that also persuade while drawing us in – for example, the details of life on board the Thorhavn:the cramped, stuffy cabins opening onto a catwalk buffeted by tearing wind and sea; the unapproachable holy of holies that is the bridge; and, as the ship heads ever southwards, the increasing cold which necessitates the constant donning and shrugging off of hats, gloves, boots, and heavy coats. Above all, there is the inescapable presence of the surrounding sea, calm and benign one moment, gathering itself into raging mountains the next. Our thirst for more technical information about this quasi-fabulous expedition is also well satisfied. Lars’s whaling fleet, we learn, is not primarily after table meat, although the flesh is stored for use in pet food; more valuable is the blubber that is processed immediately in an operation as delicate as it is monstrous. ‘Catcher’ ships harpoon the whales and transfer the bloody carcasses to enormous ‘factory’ ships; men strip off the blubber and drop it into huge pots in which it is boiled until, with a sickening stench, the whale oil separates and rises to the surface. Once it is skimmed off, Thorhavn and the factory ship are coupled and the two make their exchange: whale-oil is piped into the clean-scrubbed fuel-oil tanks and vice versa. The clear ring of authenticity (Blackadder has twice been to the Antarctic and has also documented the available historical material) around these amazing workaday practices makes for fascinating and topical reading, but without the contrast of the women’s fictional story it is possible that the research would not add up to more than an interesting article or two. Yet our investment in the human story in which we have willingly lost ourselves, our hearts frequently in our mouths – as when Ingrid and Mathilde exchange punches, or when the ‘first woman’ (no spoilers), jumping from rocking boat to rocky shore, nearly skids backwards into deathly cold seawater – is shaken when journalistic honesty torpedoes the effects of novelistic imagination.

Chasing the Light,a riveting book, raises issues that challenge, perhaps unconsciously, not only our own readerly assumptions but also the author’s best intentions.

Comments powered by CComment