- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Architecture

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Architectural distinction was conferred upon most Australian towns and cities in the nineteenth century. This was achieved largely through the construction of public buildings designed by architects employed within colonial works departments – a practice that regrettably does not exist anymore. Town halls, post offices, courthouses, hospitals, lunatic asylums, and jails were the product of highly skilled public servants who shared a common view that civic decorum was best expressed through the architecture of the Classical Tradition. Within the pantheon of these government architects, there are famous names of Australian architecture. Francis Greenway, Mortimer Lewis, James Barnet, William Wardell, Charles Tiffin, F.D.G. Stanley, and Walter Liberty Vernon are the best known among a host of others. All in some way bequeathed a certain seriousness to the endeavour of building in a place where such structures had never before stood, and in doing so contributed to defining the future mood and character of that place.

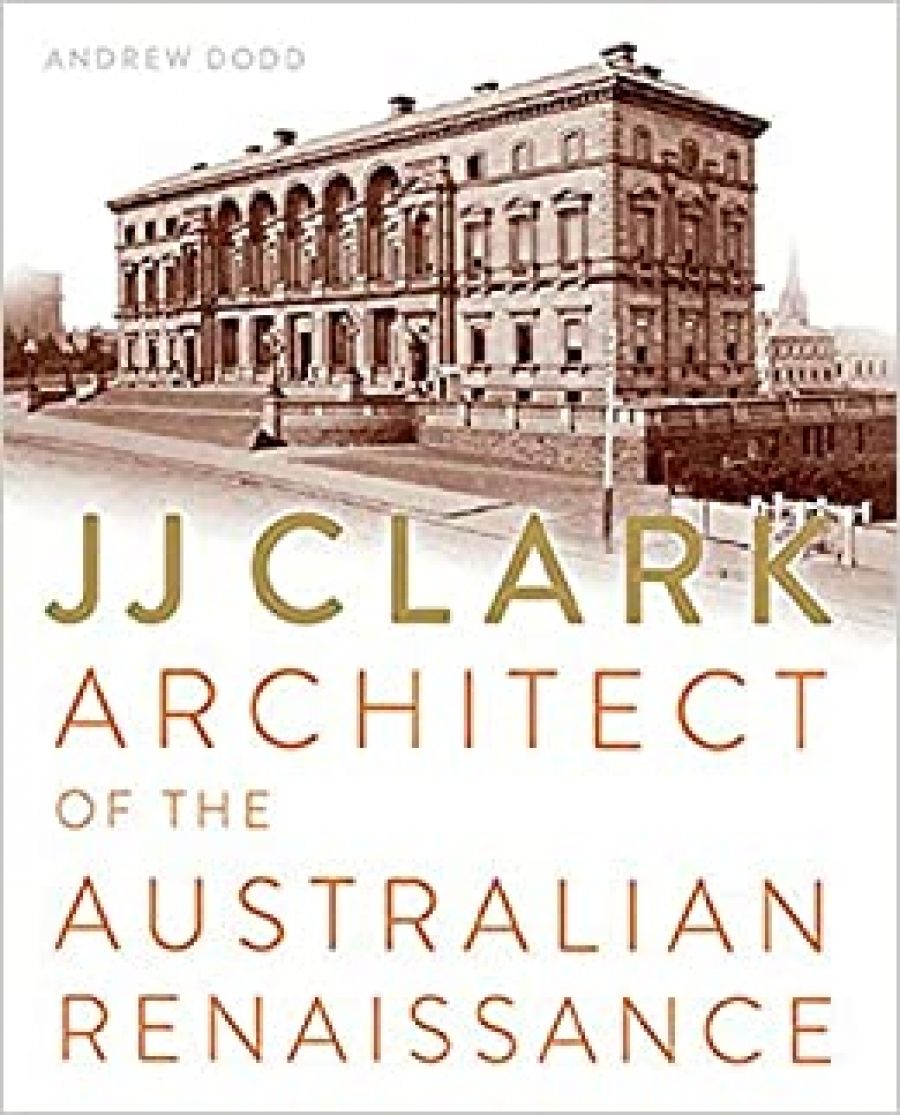

- Book 1 Title: JJ Clark: Architect of the Australian Renaissance

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth Publishing, $59.99 hb, 271 pp, 9781742233055

One architect – J.J. Clark – stands out in this distinguished group as being precocious, meticulous, a fierce competitor in intense and frequent scrambles for commissions, and with a stylistic output that displayed remarkable consistency over more than forty years. Andrew Dodd’s account of the little-known life and work of John James Clark (1838–1915) is to be heartily welcomed. Clark was, as Florence Taylor, editor of Building, described him in her posthumous tribute, ‘An Architectural Giant’. He was, in her opinion, ‘Australia’s greatest architect’. Dodd portrays Clark as a committed professional, who was also a gifted painter who took regular painting trips with Louis Buvelot, and who, at times, was frustrated by the hierarchies of public service, where recognition was not always equally bestowed and where access to private commissions was actively hindered. He also describes a man who lost his wife early (she died aged twenty-six) and a supportive father who later collaborated with his architect son Edward James Clark (1868–1950).

Clark’s drawing talents were discovered early. As a thirteen-year-old schoolboy, he produced a prize-winning map of his hometown, Liverpool, complete with a perspective drawing of his school, the Collegiate Institute. That same year his family emigrated to Melbourne. In 1852, aged fourteen, Clark was engaged by the Colonial Architect’s Office; as Dodd recounts, the boy ‘became the family’s principal bread winner’. By the age of nineteen he had designed Melbourne’s Treasury Building (1857–62), a now universally acknowledged Renaissance Revival masterpiece. This was a remarkable achievement. Clark followed this feat with the Royal Mint (1870–71), another inventive reinterpretation of the Italian palazzo, further impressing his credentials upon a city already fascinated with the artful elegance of the Renaissance Revival. Dodd argues convincingly that Clark should be given greater credit for his design contribution to Victoria’s Government House (1872–06), one of Australia’s finest works of Italianate architecture, a work generally attributed to Clark’s senior in government service, William Wardell.

The Melbourne Treasury Building, c.1875 (from the book under review)

The Melbourne Treasury Building, c.1875 (from the book under review)

With admirable though often excessive enthusiasm, Dodd attempts to find sources for all of Clark’s stylistic choices, but, in doing so, underplays the fact that the Renaissance Revival enjoyed global popularity in the mid-nineteenth century, not only in provincial England, but also from Philadelphia to Paris and from Munich to Manchester. This was due partly to the style’s modernity, its compositional adaptability to contemporary nineteenth-century programs such as large office buildings for new government bureaucracies, and for the burgeoning spaces of commerce, especially banks and insurance companies. Another reason for the style’s popularity was that stone facing and cement render ornament could easily be applied to relatively humble brick sub-structures. For a government intent on fiscal responsibility, the Renaissance Revival guaranteed both symbolic propriety and constructional expediency. Dodd outlines not just Clark’s superior design abilities in this regard, but also his flair for winning competitions and, if not being placed first, then using political and professional argument to ensure that his design was preferred above others. Dodd also shows Clark to have been an architect of some mobility – a fact that is today largely unappreciated. Architects in the nineteenth century moved across the Australian continent as economic times dictated, and Clark was no exception. While the events of ‘Black Wednesday’ – the sacking of 200 staff within the Victorian Public Works Department on 9 January 1878 – would have been distressing, ending a twenty-five-year working association, it meant that Clark was free to move to Sydney to practise (not very successfully) with his engineer brother George, and then, following success in a competition, to Brisbane, where, in private practice but simultaneously as Queensland Colonial Architect, he designed and oversaw that city’s most impressive classical work, the Treasury Building (1886–1928), an original composition of multiple arcaded loggias over three stories with no classical precedent and a direct response to Queensland’s subtropical climate. It is another masterpiece.

While Clark is known for these accomplished civic piles, less well known is the fact that he was also a specialist in hospitals and asylums (especially between 1896 and 1909 in Perth during a stint in the WA Public Works Department), completing designs for numerous sites including asylums for Kew, Ararat, Beechworth, and Toowoomba, and hospitals, or parts thereof for Maryborough, Brisbane, Perth, Geraldton, Newcastle, Maitland, and, with his son, his largest and most impressive hospital taking up an entire city block, the Melbourne Hospital (1905 –15), known for many years as Queen Victoria Hospital. Clark was also, towards the end of his career, an expert stylist in what is today described as the Edwardian Baroque, and two of his finest works in this regard are the Auckland Town Hall (1907–11) and Melbourne’s City Baths (1901–04).

This is a fine book, well written and based on detailed archival research. For the non-architectural reader, there are also helpful definitions of style. But its important content, in the opinion of this reviewer, deserves a much more handsome format and, dare one say it, glossy paper. Rather than this volume’s carefully designed sepia tones, the scale, beauty, and ambition of Clark’s work demands large-scale archival photographs and full-colour reproductions of his exquisite and elaborate drawings, which, held mostly by the Pictures Collection of the State Library of Victoria, are in themselves beautiful objects. Visual immersion in the sheer quality of these buildings would impress upon all readers not just Clark’s technical competence, especially with regard to advancing hospital design, but also the breadth and scope of his unequalled contribution to defining Australia’s civic architecture. Dodd correctly concludes that J.J. Clark was an architect of the nineteenth century and that, on his passing, the great age of the Classical Tradition had also passed. However, Clark’s surviving built works continue to impress, and Andrew Dodd’s excellent book further guarantees that Clark’s professional and personal story now complements that enduring legacy.

Comments powered by CComment