- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

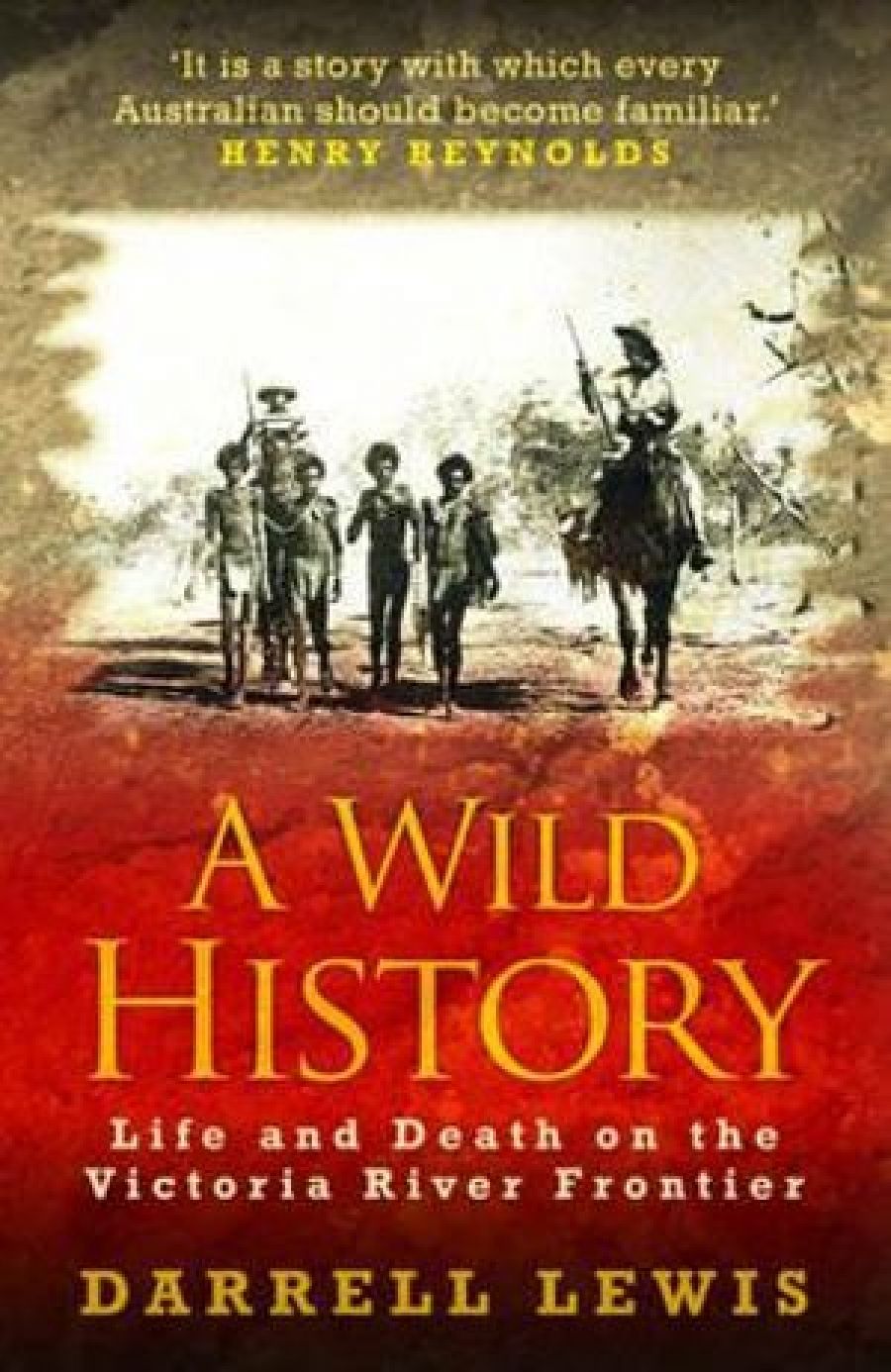

- Book 1 Title: A Wild History: Life and death on the Victoria River frontier

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $29.95 pb, 342 pp, 9781921867262

The Victoria River District is unusual in its lack of family dynasties with roots in the pioneer generation. The early settlers, who were occupying vast tracts of land, tended eventually to sell up and return to something more like civilisation. Lewis puts this down to the harsh climate, and to the remoteness and isolation, which lacked the ameliorating influence usually provided by country towns. With the high turnover of station staff, there has been ‘a weak transmission of local knowledge’. The irony is that Aborigines, who, unlike the settlers, ‘don’t come from somewhere else, stay for a period and then leave’, are actually ‘the “keepers” of much “European” history’. Lewis knows the District’s Aboriginal communities well, and is able to draw on the perspective on European settlement of those who so fiercely resisted it.

Lewis stresses the sophistication of Aboriginal land use, particularly in the deployment of fire. ‘They knew that burning at the appropriate time would promote the flowering of certain plant species, and the growth of particular food plants, or would attract desirable animals to the burnt area, and they knew that if they burnt certain food plants in patches over time, the plants would fruit over an extended season.’ This seems consistent with the argument recently advanced by Bill Gammage in his prize-winning The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia (2011), which presumably was not available to Lewis when he was writing A Wild History. Early European expedition reports described the country as being ‘splendidly grassed’ and ‘lightly timbered’, a product, we can now appreciate, of Aboriginal land use practices; Lewis’s innovative use of repeat photography shows how European settlement has changed the environment, most particularly in the increase in trees in much of the District.

At the heart of A Wild History, however, is a meticulous account of the halting progress of European settlement and the varied opposition it faced from the District’s thirteen or so Aboriginal peoples or language groups. On his 1855–56 expedition along the Victoria River, Augustus Gregory was greeted with suspicion by the Aborigines, but there was ultimately some friendly contact. The settlers, however, who soon showed their intention of staying, were met with understandable hostility, particularly when they began to occupy the plains with their cattle. Increasingly, the Aborigines were forced back into the rough country, from where they would make strategic raids on the rudimentary homesteads of the early days, or on travellers passing through difficult country, such as Jasper Gorge. And, of course, from the Aboriginal point of view, their hunting grounds having been curtailed, cattle were fair game. Reprisals by the settlers, and later the police, were often harsh, and the evidence suggests there were a number of massacres. Lewis’s analysis of this frontier violence is always painstaking and judicious.

Initially, settlers exploited tribal divisions by employing Aborigines from outside the District. When, after twenty years of intermittent conflict, the Wardaman, who were possibly the fiercest warriors in the District, gave up the fight in the early 1900s and came into the stations, it signalled the end of organised Aboriginal resistance. In camps attached to the stations, they would become an important part of the settlers’ labour force. As Lewis points out, ‘soft’ resistance, such as cattle killing, continued, and indeed as late as the 1920s there were still some unfriendly Aborigines in the rough country.

Lewis, however, wants to offer some homage to the settlers as pioneers. The most notable is ‘Captain’ Joe Bradshaw, who, we are told, is ‘one of the great entrepreneurs of northern Australia’ and is awarded a chapter to himself: born in Victoria, he came from a wealthy background and quickly acquired properties in the Kimberley and Arnhem Land, as well as the Victoria River District, and had interests in mining, railways, and shipping. In fact, because of the wide spread of his interests, ‘he spent comparatively little time living on any of his stations’. We know surprisingly little about him as a person. We don’t even know where the title ‘Captain’ came from, but Bradshaw was a sailor and it is suggested, although with no great authority, that it might have been bestowed upon him by a Sydney yachting club. He had published papers on northern Australia and was a Fellow of the British Royal Geographical Society. And, although Lewis doesn’t mention it, he had a wife and son back in Victoria, though presumably he spent ‘comparatively little time’ with them, too. According to a report in the Farmer and Grazier,‘Captain’ Joe claimed to have always treated ‘Binghis’ (Aborigines) and Malays with ‘consideration and justice’, but added that there were ‘times when quick and stern measures are necessary to meet emergencies’. How stern was left to the imagination, but it is clear that Bradshaw saw himself as the lawgiver dispensing ‘justice’.

Lewis is fascinated by the ‘network’ of highly mobile pastoral workers whose ‘social currency’ was ‘stories’ passed on round ‘many a campfire’. He admits that the District, being a backwater, ‘collected rejects from more climatically congenial though less socially tolerant climes’, and, characterised by Lewis as ‘battlers’, that they were not a particularly likeable bunch. Cattle duffing was the least of their crimes; some were known for their viciousness towards Aborigines. Nor was there necessarily much camaraderie between these ‘hard men’ (‘hard’ being a euphemism, as in the case of Jack Beasley, ‘remembered by Aborigines as a very hard man and one of the main culprits in early massacres’).

There is a Gothic flavour to some of the frontier violence that Barbara Baynton would have relished. David Byers was one of the very few early station managers who brought his wife with him. When Byers disappeared in mysterious circumstances in the bush, Mrs Byers was so distraught, screaming and weeping, that the constable, who seemed more irritated than sympathetic, reported that ‘it was impossible to obtain particulars of Byers Age etc’ from her. On the other hand, ‘Brigalow Bill’ Ward had an Aboriginal ‘wife’, known as Judy, whom he treated badly. When Brigalow Bill was speared by bush Aborigines, it emerged that for Judy it was a calculated act of revenge. Before the attack she had removed his pistol, taking it down to the river in a bucket, and after the killing she and other women urinated on his face, ‘a sign of contempt for his sexual demands’. These are two of the very few incidents involving women, because, as Lewis admits at the outset, the history he is writing is largely white male.

A Wild History is a fine piece of scholarship, exemplary in its judicious interpretation of both white and Aboriginal oral tradition, as well as the documentary sources. Just as the story begins with ‘the aura about the country’ firing Lewis’s imagination, so at the end it is the landscape, majestic, beautiful, forbidding, that has the last word. Keith Windschuttle could learn a lot from this book.

CONTENTS: SEPTEMBER 2012

Comments powered by CComment