- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Portugal

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Story of a coup

- Article Subtitle: Portugal’s 1974 revolution

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

More than a decade ago, two academics browsing in an antiquarian bookshop in Lisbon stumbled across a Portuguese language account of the 1974 Captains’ Coup by Wilfred Burchett. A little digging revealed that while the volume had been translated into Italian and Spanish in the year of its publication, with a Japanese edition appearing the year afterwards, no English language edition had ever been produced. Indeed, nobody seemed to know where the original manuscript might be found. A chance encounter and a helpful librarian located the original typescript in the Burchett papers at the National Library of Australia in Canberra. While this detective story makes for an entertaining preface, it is telling that having tracked down and meticulously prepared the manuscript it then took the editors more than ten years to find a publisher for the first English language edition of The Captains’ Coup.

- Book 1 Title: The Captains’ Coup

- Book 1 Subtitle: From dictatorship to democracy in Portugal (1974-1976)

- Book 1 Biblio: Verso, £25 hb, 352 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781804298367/the-captains-coup--wilfred-burchett--2025--9781804298367#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

If this timorousness hints at the increasingly constrained commercial environment within which publishers work, it surely says far more about Burchett’s diminished status as a touchstone for Cold War cultural and political contention. Once, the very mention of his name brought diehard Burchettistas and the cold warriors of Quadrant and the Murdoch press to frothing invective. Now, the clear lines of the Cold War, which Burchett so flagrantly crossed, look like maps from a mythical kingdom.

That this book took so long to appear also implies that there is little public interest in the Portuguese revolution or its global implications. The Carnation Revolution of 25 April 1974 was remarkable in so many ways. Not only did it remove the longest-lasting fascist regime in Europe, but this revolutionary change was instigated by a leftist military coup organised and led by the captains who formed the Portuguese Armed Forces Movement (MFA). In light of the bitter experience of the previous decade, with rightist military dictatorships in Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay unleashing a bloody pursuit of the left and its sympathisers, Burchett reacted in wonderment to a military putsch from the left dedicated to the goals of democracy, development, and decolonisation under civilian leadership.

The end of fascism in Portugal hastened the end of its colonial empire in Africa and Southeast Asia. For decades Portuguese soldiers, many of them conscripts, had been fighting and dying in south-eastern and south-western Africa where independence movements sought the self-determination by then enjoyed by former British and French colonies. By the early 1970s, the colonial wars were swallowing almost half of Portugal’s GDP, retarding much-needed development at home and wasting thousands of lives. The captains in the MFA, the men most familiar with the pointlessness of these wars, realised that ‘the only way to end the war was to end the regime’. And so they did.

In the wake of the coup, between 25 May 1974 and 15 January 1975 Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, and Angola signed agreements with Portugal, thus emerging from more than five hundred years of colonial vassalage as independent sovereign states. Yet it was far from smooth sailing. Angolan independence ushered in more than twenty-five years of civil war. Closer to home, in East Timor, the collapse of Portuguese rule was succeeded by Indonesian invasion, annexation, and a brutal occupation that lasted until the eve of the millennium. Macau, the last European territory in continental Asia, was quietly returned to Chinese rule in 1999. The fate of millions in Europe, Africa, and Asia turned on the captains’ coup. The story of the coup, and its far-reaching consequences, deserves to be better known.

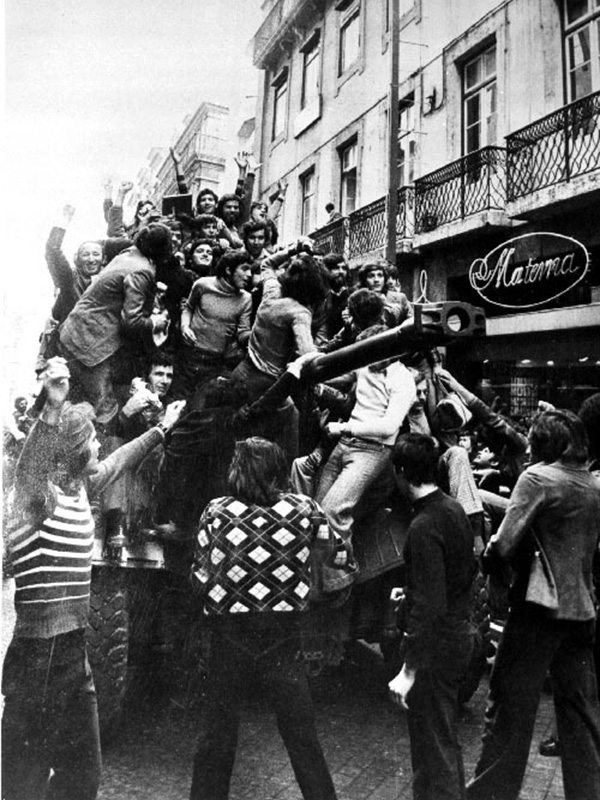

Portuguese people on an armoured car during the Carnation Revolution, 25 April 1974 (Centro de Documentação via Wikimedia Commons)

Portuguese people on an armoured car during the Carnation Revolution, 25 April 1974 (Centro de Documentação via Wikimedia Commons)

Burchett arrived in Lisbon on the first plane from Paris after the coup. The coup and the popular revolution that it triggered had closed Portuguese airspace for a few days. His fame among local leftists, especially his work on Vietnam, opened many doors as he sought to understand the process that was in train, identify its principal players, and scope out its potential outcomes. The admirable clarity of his account of the revolution and its immediate aftermath, and the vividness with which it is rendered, owe a great deal to his sources.

Despite some special pleading on behalf of the Portuguese Communist Party, in the main Burchett lets his interviewees do the talking. Through them he offers a compelling account of the revolutionary transformations in governance, press freedom, land tenure, and the economy that began within days of the coup. Thus, it is an artillery captain who details the formation of the MFA, the personalities of its leading figures, the grievances that led them to such a bold enterprise, and the euphoric rapprochement between the people and the armed forces that they had long scorned.

An agricultural labourer describes the grinding poverty the peasants suffered in the latifundia, while Burchett adds data detailing high rates of illiteracy, infant mortality, undernourishment, and emigration from the country’s rural areas. A fisherman details the effects of monopoly capitalism and under-investment for those who made their living from the sea. Life was little better for the urban working classes. Portuguese per capita income was not only the worst in Europe by some margin, it lagged behind Mexico and Panama. In the years before the coup, the Portuguese consumed only a quarter of the average daily dairy intake of those in West Germany and a third of the daily diet of meat in France. As one doctor remarked: ‘Is it any wonder we are breeding midgets?’

The book is at its best when Burchett describes the attempted counter-coups that took place in September 1974 and March 1975. His breathless account of events that occurred in the presidential palace at Belém on the night of 28 September 1973 offers a gripping, minute-by-minute record of moves to install a counter-revolutionary clique supported by the country’s monopolist oligarchy.

His worm’s-eye view of the events, again sourced from an eyewitness, demonstrates the apparatus of reaction at work and the means by which it was defeated. The people were at the heart of this force – and not in an abstract sense. Thousands of ordinary Portuguese, when alerted to the counter-coup, left their homes to surround key ministries, obstruct the passage of counter-revolutionary figures, and converse directly with the soldiers turned out to enforce the putsch. Burchett can hardly believe his eyes as, time and again, the people take to the streets en masse to praise and then defend the military and its coup leaders. Half-expecting a Portuguese Pinochet to suddenly emerge from the ranks, he is left to ruminate on the doctrinal distinctions between the centre, socialist, and hard left within the MFA.

Rebuilt and burnished by decades of EU largesse, today’s Portugal has come a long way from the backward, impoverished, overwhelmingly agricultural fiefdom of the early 1970s. It is healthier, and wealthier, if unequally so. Young Portuguese would struggle to recognise the country their grandparents fought to change. Though I doubt Burchett would have much enthusiasm for the country today, his book offers a vital account of the first steps in its transformation.

Comments powered by CComment