- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: More hero than man

- Article Subtitle: What the Robesons’ tour said about us

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australians and New Zealanders loved Paul Robeson. Socialists, peace activists, and trade unionists held him up as their champion, the face of defiance amid Cold War harassment. Conservative theatre critics swooned at his golden bass baritone. Māori rugby players called him ‘brother’. Eastern European migrants wept to his song about the Warsaw Ghetto. Even an FBI informant could not deny he was a ‘great and superb artist’.

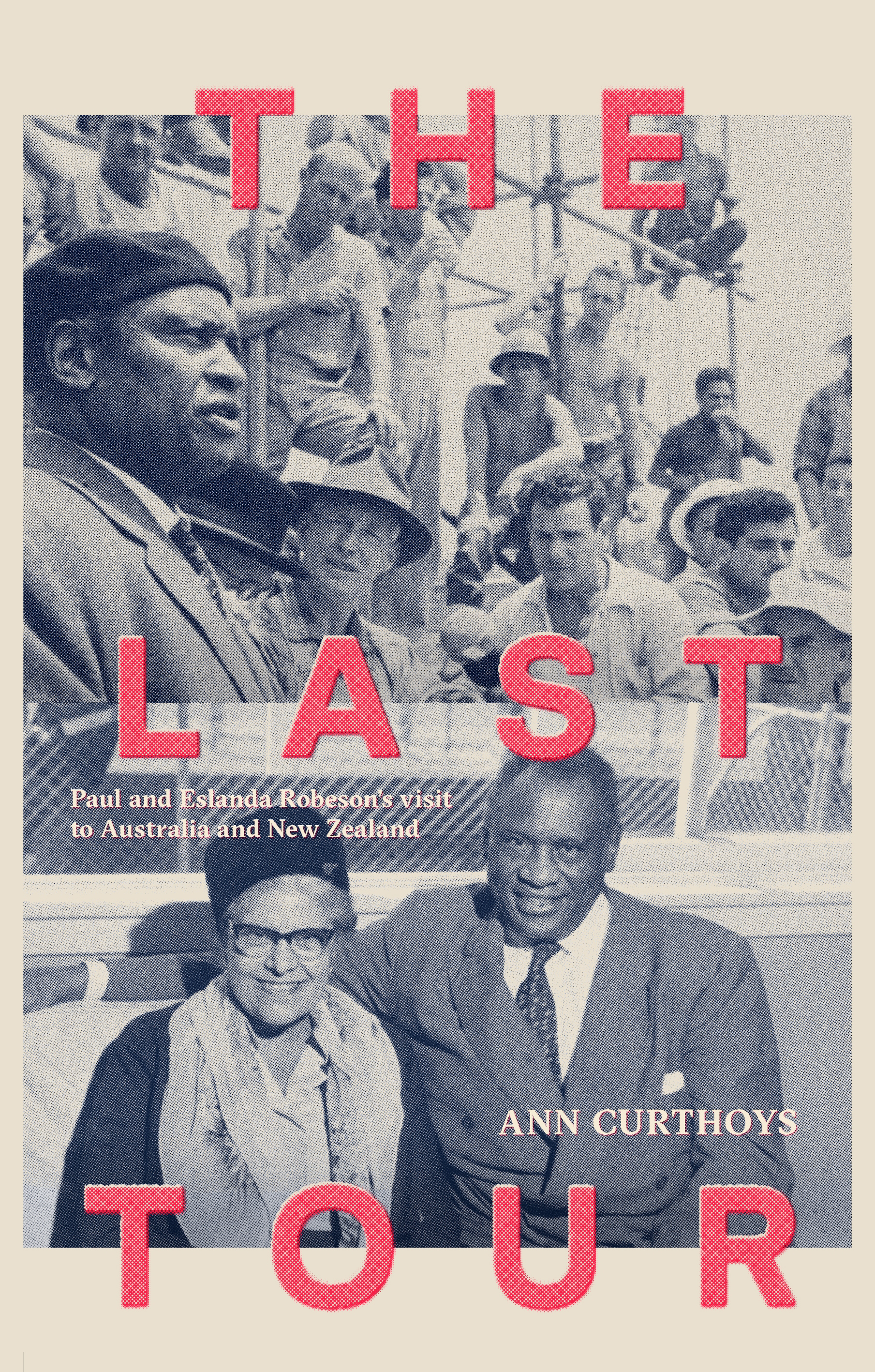

- Book 1 Title: The Last Tour

- Book 1 Subtitle: Paul and Eslanda Robeson’s visit to Australia and New Zealand

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $39.99 pb, 386 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780522879896/the-last-tour--ann-curthoys--2025--9780522879896#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

The Last Tour, Ann Curthoys’s chronicle of Paul and Eslanda Robeson’s 1960 journey through New Zealand and Australia, captures the warmth and affection that greeted the couple throughout their nine-city, three-month tour. In rich chronological order, she recounts the media-studded airport receptions, the thunderous concert hall ovations, and the heartfelt emotion of the seven informal concerts. At each point, Paul Robeson emerges as an extraordinarily charismatic man – at once majestic and intimate, unwavering in his radical political convictions yet unthreatening and disarming to mainstream audiences.

Curthoys also recovers the lesser-known contributions of Eslanda, an anthropologist and journalist whose lunchtime talks for the World Peace Council added a scholarly dimension to questions of decolonisation, women, and global governance. Most compelling is Curthoys’s account of the couple’s deepening engagement with Māori and Aboriginal issues, which they understood from an international perspective, drawing connections with the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, and the industrial action of Welsh coalminers.

Of course, Paul Robeson’s relationship with Australia and New Zealand began long before he set foot in the country. Curthoys identifies a remarkable number of antipodean travellers who caught Robeson’s electrifying performances in London, New York, Panama, and Moscow. Since 1950, the Australian left had rallied behind the ‘Let Paul Robeson Sing’ campaign after the US government revoked his passport, preventing him from touring for eight long years. The correspondence and friendships nurtured through these networks paved the way for his impromptu performances for peace activists, waterside unionists and, most famously, the construction workers at Sydney’s Opera House. The left admired him with such intensity; he seemed more hero than man.

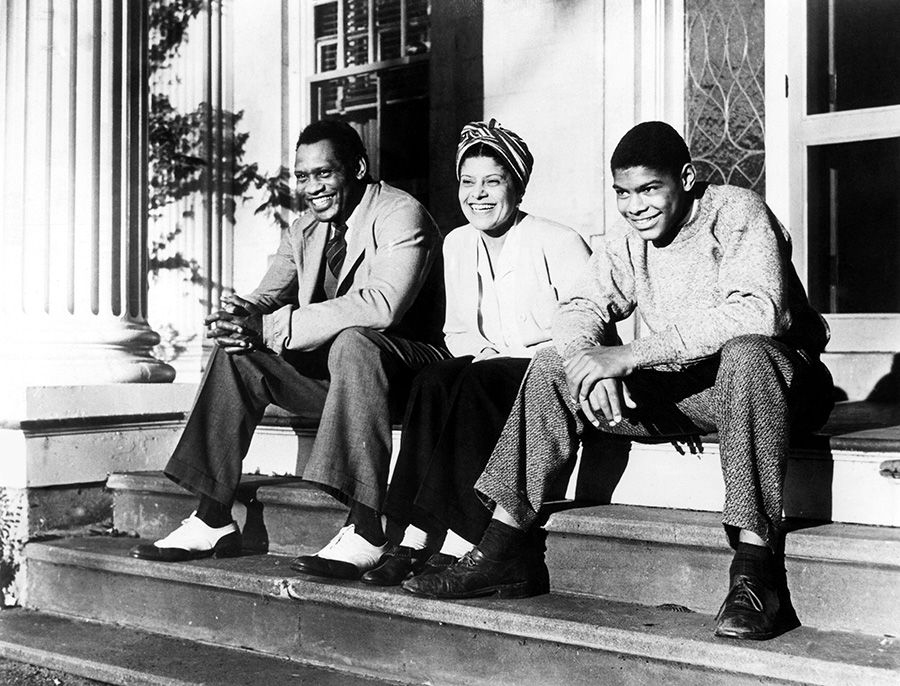

Paul Robeson, Eslanda Robeson, and Paul Robeson Jr at their house in Enfield, Connecticut (Everett Collection Historical/Alamy)

Paul Robeson, Eslanda Robeson, and Paul Robeson Jr at their house in Enfield, Connecticut (Everett Collection Historical/Alamy)

In contrast, the general public knew Robeson through his films and records, some dating back to his early career. To his great surprise, audiences still remembered the 1935 film Sanders of the River, a White Man’s Burden narrative about a failed rebellion in colonial Nigeria, and clamoured to hear ‘The Canoe Song’, an ode in praise of a pith-helmeted British administrator. Robeson had long denounced the film as ‘imperial propaganda’, but he obliged, tweaking the lyrics to liberate them from their colonial clutches. He had done the same with ‘Old Man River’. It is easy to forget that Robeson’s most famous song was a faux-spiritual penned by two white Tin Pan Alley songsmiths for Showboat, a minstrel-styled stage play and film awash with mammies and southern belles. Robeson’s lyrical modifications illustrated the way he navigated the identity white audiences foisted upon him while transcending the stereotypes that straitjacketed Black entertainers – a state of ‘two-ness’ that the sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois called ‘double-consciousness’.

Curthoys shows that Paul Robeson’s political pragmatism was equally nuanced. Easily cast as a Moscow-loving pinko, he defused Cold War paranoia, using the universality of the pentatonic folk scale to sound his message of common humanity. He reserved more complex critiques – premised on theories of postcolonialism, racial capitalism, and Indigenous justice – for unofficial appearances. In short, Robeson was a masterful diplomat. He carefully curated a persona that smoothed over contradictions and revealed only what he wanted the public to see. Stalinist Russia treated him like an artist. White Australia felt like home.

Curthoys’s reluctance to engage with the Robesons as biographical subjects feels like a missed opportunity. Several times, I wished she had broken free from the tour itinerary and reflected on the psychic cost of being Paul Robeson. What did it take to sing ‘Old Man River’, ‘Joe Hill’, and ‘Water Boy’ over and again, as if they were fresh and spontaneous? She alludes to his exhaustion but does not fully probe the pressures borne by Black entertainers who emerged in the first half of the twentieth century and crossed over into the white show business world – an exhaustion that we might now call ‘weathering’.

Take, for instance, the cognitive dissonance Robeson must have experienced when Hal Lashwood invited him to appear on the Christmas 1960 edition of his television show, Hal Lashwood’s Alabama Jubilee. Lashwood was a well-known figure in Sydney leftist circles and targeted as a radical by ASIO. He was also the son of a blackface performer and continued this tradition on his Saturday night variety show. He claimed his brand of blackface honoured Black suffering – a sentiment traceable to the 1886 tour of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, when white Australian audiences tearfully embraced slave spirituals without connecting the sorrowful laments of a ‘poor, downtrodden race’ with the British colonisation of Australia.

Evidently, Lashwood had never picked up a copy of Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel, Invisible Man, and fathomed a Black protagonist wrestling with the identities forced upon him. He had not ingested the maddening paradox that Frantz Fanon set out in his 1952 treatise, Black Skin, White Masks: to assimilate meant accepting white hegemonic values and internalising Black inferiority; to refuse to assimilate meant being cast as a monstrous primitive. Robeson grappled with this paradox in his comments on Indigenous culture, just as he grappled with Lashwood’s invitation. He ultimately decided to appear on the show, singing to six children – two Aboriginal, two Asian, and two white. Once again, he demonstrated the hard-headed political calculus of a Black entertainer in a white show business world.

The incident also reveals the Australian left’s preoccupation with the class struggle of the white industrial proletariat and their narrow view of international solidarity. On several occasions, Peace Movement activists were unable to meet the Robesons’ requests and connect them to Aboriginal communities, though they eventually met a number of Indigenous campaigners.

The couple tolerated the Australian left’s shaky grasp of race until they viewed a documentary exposing the poverty, hunger, and sickness suffered in a central Australian Aboriginal community. Here the Robesons’ tidy compartmentalisation broke down. As he told it, Paul returned to his hotel room and ‘wept and wept’. From then on, he and Eslanda held the Australian left to account, pressing them to prioritise Indigenous justice. They promised to return and join in the struggle.

They never did. Nine months later, Paul Robeson slashed his wrists in a Moscow hotel and spent three years battling depression. Eslanda Robeson had only five more years to live. However, the legacy of their visit would endure, resonating through music, politics, and memory.

The Last Tour is a welcome contribution to the scholarship of African diasporic experience in Australia and New Zealand. Curthoys has lovingly synthesised a wealth of material to create an insightful social and political history of the tour that captures the complex and multi-layered relationship between audience and artist. She has also recovered a forgotten intellectual in Eslanda Robeson, too often cast as the artist’s devoted wife. In Curthoys’s hands, the Robesons’ journey becomes more than a tour; it is a mirror held up to the nations they visited.

Comments powered by CComment